FOR many men returning from the Front just over a century ago, the sound of machine gun fire was replaced with something just as frightening – coughing and sneezing.

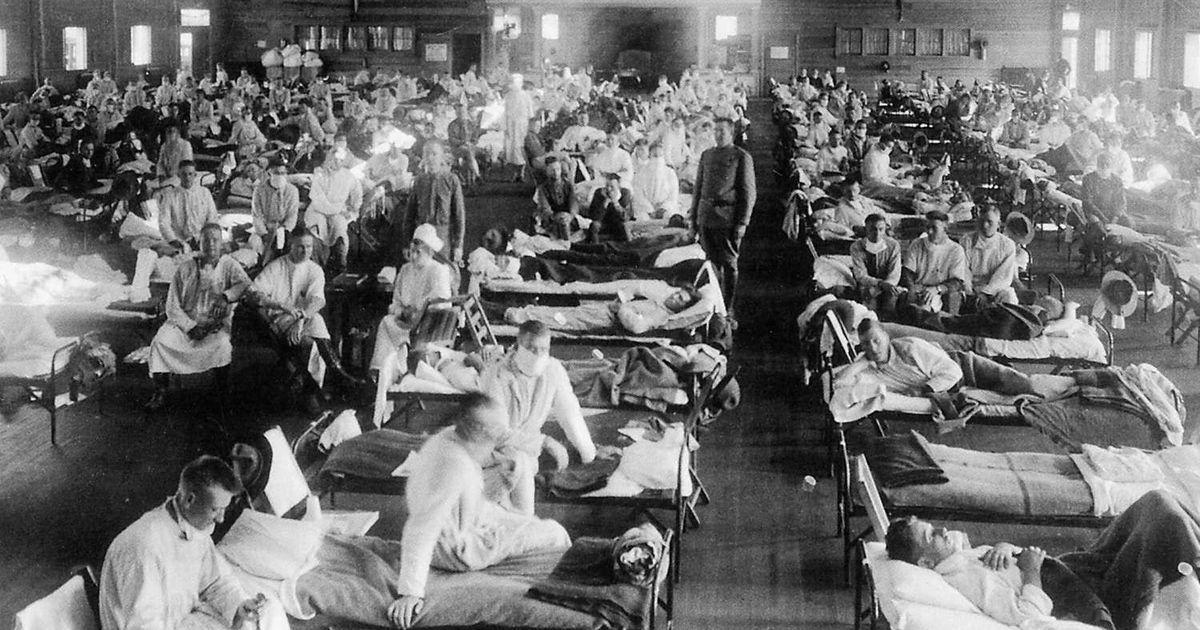

The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 and 1919 killed between 50 and 100 million people worldwide, including about one million First World War servicemen.

When the pandemic reached Bradford, quarantines and temporary hospitals were set up across the district. Many of the patients were exhausted soldiers returning from the war. They included Private Reginald Lloyd, a young teacher at Bradford Grammar School, who served with the Army Service Corps as a motor driver.

Born in Wales, Reginald was captain of his Oxford college rugby team in 1909-10. In 1912 he arrived at Bradford Grammar School to teach Classics and English, and to assist the boys with rugby. Nick Hooper, retired head of history at BGS, researched Reginald as part of his extensive study of former pupils in the First World War. He finds his story particularly poignant as the deadly disease ended his life just before what would have been a match of his lifetime.

After being examined on January 23 1919, Reginald went on demobilisation leave. “Two forms in his Service Record note that he was discharged ‘for Cough’ - this may be the first sign of his fatal illness,” says Nick. “He returned to Bradford and clearly his return was noted for on February 15 the Yorkshire Rugby Union selection committee picked him to play as a three-quarter against the New Zealand team at Bradford on March 8, alongside FE Steinthal OB, of the Ilkley club and a pre-war England international.

“Sadly Lloyd may already have been too ill to be aware of this selection. The doctor who attended him stated ‘My opinion is that this condition was undoubtedly brought about by his service in the army’. He died from cardiac failure brought on by influenza and pneumonia and was buried at Scholemoor. His funeral was attended by representatives of masters and boys from the school.”

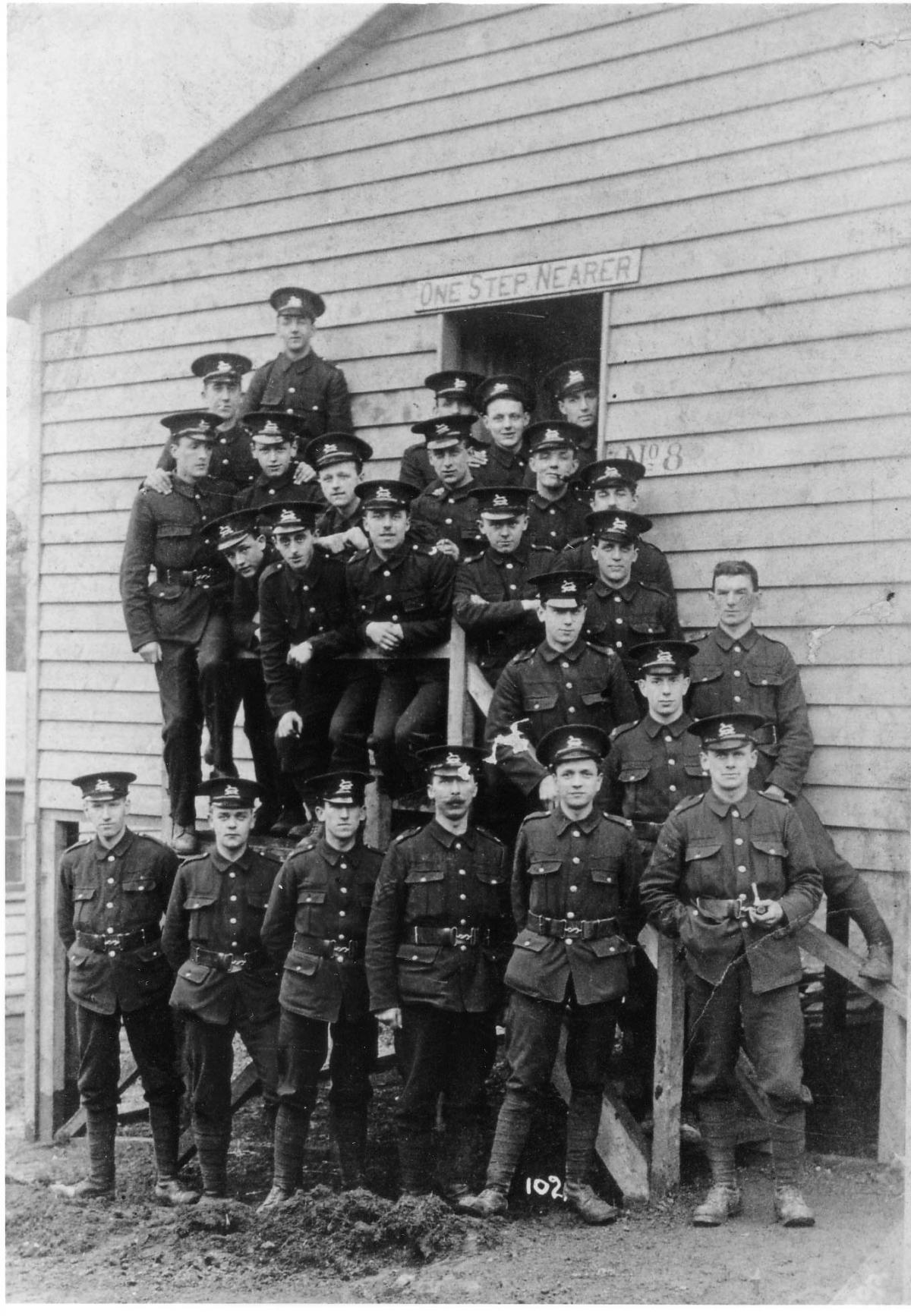

German officers and their men also fell victim to the pandemic, when it swept through Raikeswood Prisoner-of-War Camp at Skipton early 1919. Of 683 Germany prisoners at the camp, 47 died; 42 of them in Morton Banks military hospital in Keighley and five in the camp. The funerals took place at Morton Cemetery and the surviving prisoners designed a memorial. In the 1960s the graves were moved to Cannock Chase German Military Cemetery in Staffordshire.

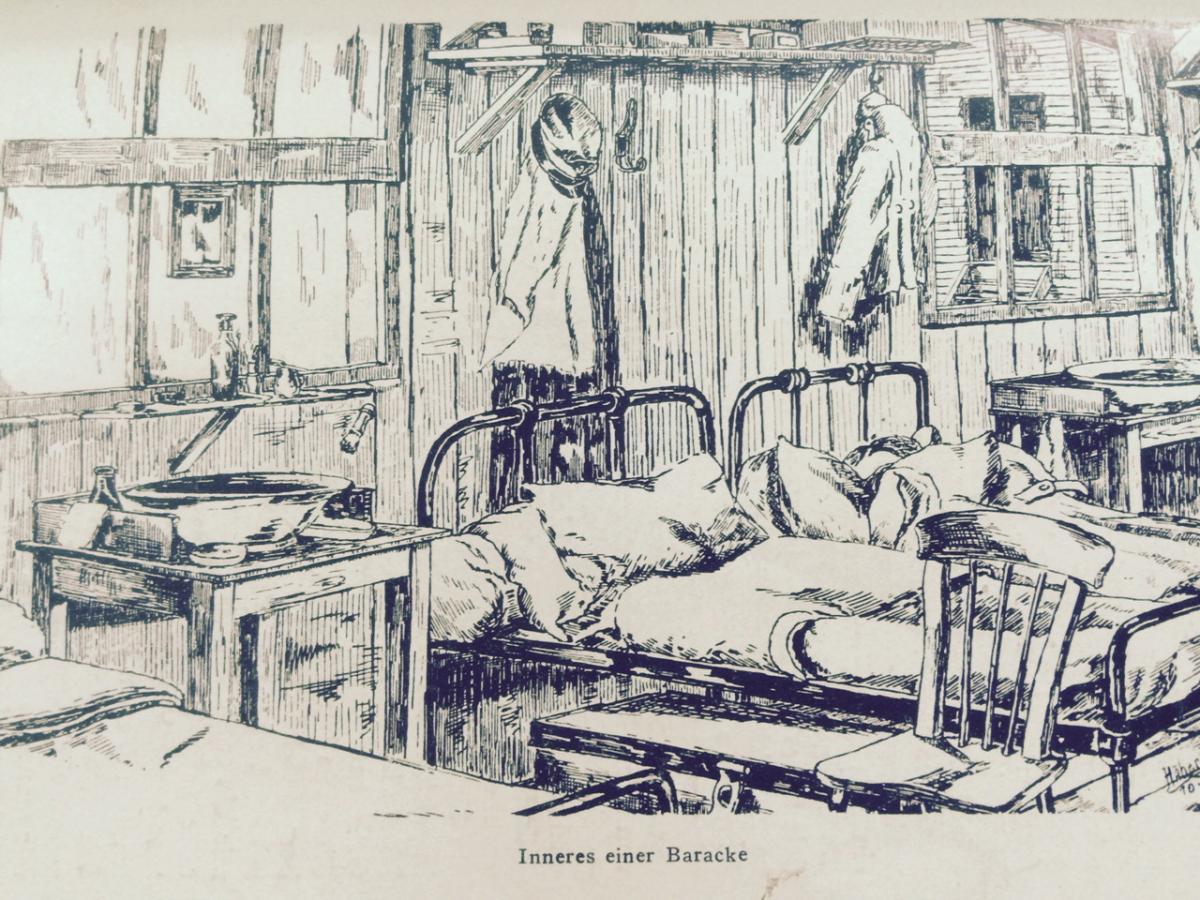

The outbreak is detailed in Kriegsgefangen in Skipton, a book published in 1920, compiled from prisoners’ smuggled diaries. Extracts read: “On February 12 five orderlies fell ill with influenza. The sick were treated in their barracks at first. The illness soon spread...on February 15 it spread to the officers. It would develop as follows: after an incubation period of two to three days, during which the symptoms were a lack of appetite and tiredness, a fever would suddenly break out...accompanied by fits of shivering, high temperature and headache. The patient would suffer from constipation and lack of appetite, he would feel weak and appear apathetic. Additional symptoms were coughing, nosebleeds, backache and aching limbs, and occasionally an ear infection. The fever would peak on the 4th or 5th day when the crisis point was reached. In most cases the temperature would gradually fall and the patient would begin to recover. However, lung damage and heart problems were often lasting consequences. Complications arose due to tissue and nerve damage. Almost all the sick, especially the most seriously affected, were no older than 30.”

Another extract reveals the “sombre” mood in camp: “Classes and lectures were suspended. The usual noisy comings and goings of mess rooms ceased. The few who were still healthy ate at sparsely occupied tables and went about with tired faces, strained by worry about their own fate. One constantly saw stretcher bearers everywhere; we asked reluctantly which comrade lay under the blanket. Vehicles rattled through the camp gates, stretchers were loaded in.

“With fear and hope in our hearts, our eyes followed the departing vehicles. In the sickbays our comrades lay in feverish delirium: strong men, soldiers prepared to bear anything, even death; now frightened men with shattered nerves. One asked for a rosary, another leapt out of bed in his fever thinking his mother was waiting for him.

“The camp hospital was soon overcrowded”...”Ten barracks, formerly dining and living quarters, were converted into makeshift sickrooms. Eventually the War Office gave permission to accommodate the sick at Morton Banks; designated a war hospital since the Somme offensive. Eventually two buildings were allocated to German patients. Sadly, too late for many.

“One great difficulty was communication between patients and carers. At the request of the senior German officer, one of our comrades was sent to the hospital as an interpreter.

“Recovering officers were allowed to walk in a section of the hospital gardens. A protestant and a catholic priest frequently visited the sick.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel