ALBERT Waxman was at home with his family the night SS officers broke in. “We ran up to the attic. They broke everything,” recalled Albert. “Stoves were thrown out of the window, beds destroyed, windows smashed. There was nothing left. We fled in our nightclothes.”

It was November 9, 1938 - Kristallnacht, when Nazi leaders unleashed pogroms against Jewish communities in Germany and Austria, destroying and looting businesses, homes and synagogues.

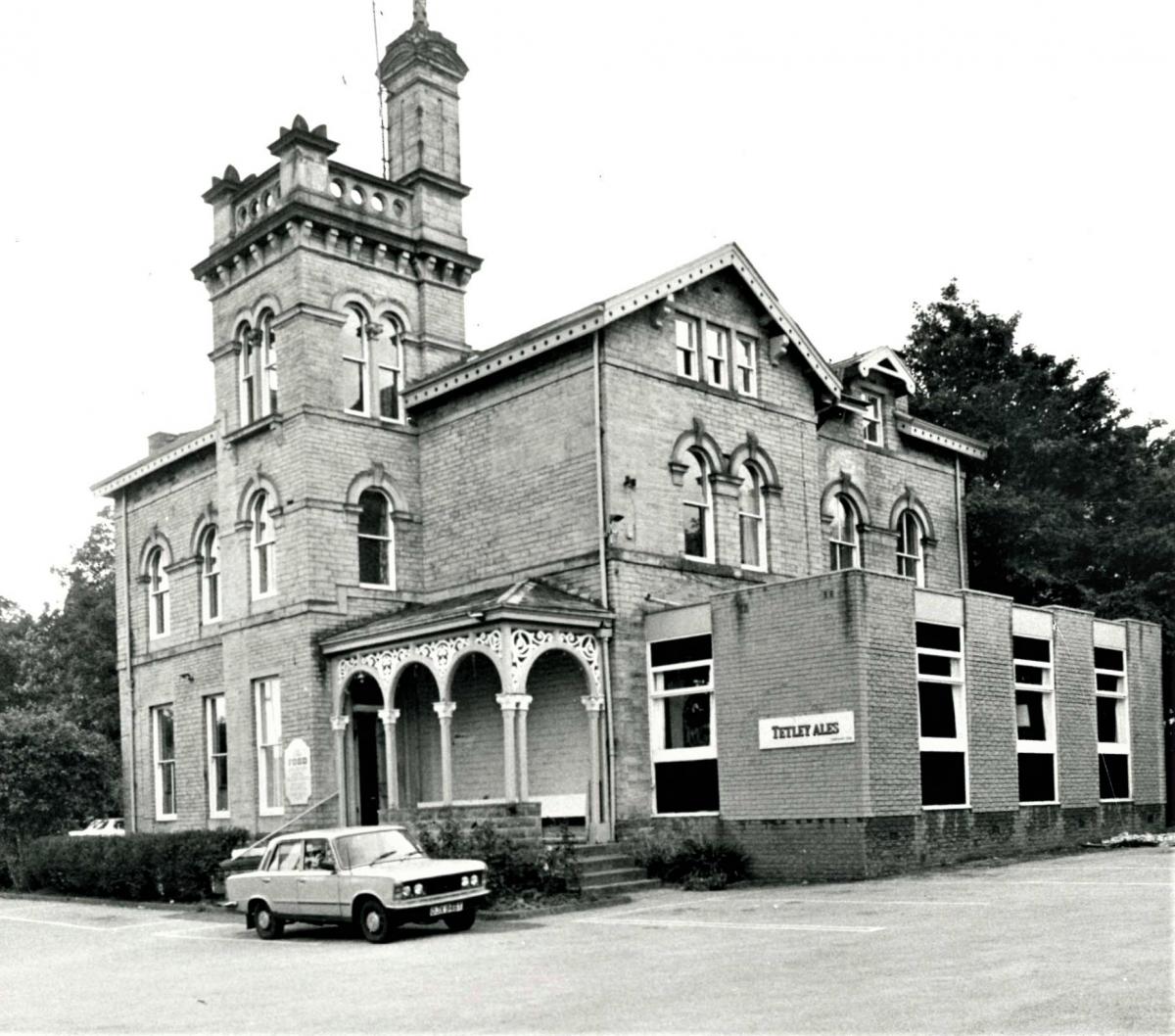

It sent shockwaves around the world. In Bradford, one evening shortly after Kristallnacht, Oswald Stroud stressed the plight of Jewish children to the Bradford Committee for German Jewry. “There must surely be some among us who can provide a home for one or two children,” he said, in a T&A report. Mr Stroud - founder of worsted manufacturers Stroud Riley Drummond on Lumb Lane - suggested training youths in business or as domestic servants. His wife suggested a refugee home. So it was that a house on Parkfield Road, Manningham, was bought and furnished, by both Bradford’s Jewish community and non-Jews.

Albert Waxman was 14 when he arrived there, in March 1939, with 23 other boys who had escaped Nazi-occupied Europe on the Kindertransport, bringing 10,000 Jewish children to safety.

The theme of Holocaust Memorial Day, held last week, was ‘Stand Together’, highlighting how we should unite against division and the spread of hatred in society. Over 80 years ago, Bradford people stood together to open up the Jewish Refugee Hostel. “This hostel, in the security of a provincial city, will be a blessed haven to these children, torn from their parents,” the T&A reported in January 1939.

Albert died last summer, aged 94. A prominent industrialist and philanthropist, he was the former Bradford Hebrew Congregation president at the Orthodox Synagogue in Shipley, which closed in 2013. In 2012 he told the T&A about his time at the Jewish hostel, and how he tracked down the other boys 50 years later.

Born Albert Wachsman. the son of a draper, he was the only child from his town, Saarbrucken in Germany, chosen for the Kindertransport. A stroke of luck had already saved the family from deportation to Poland. In 1937, his Polish-born parents were arrested, but because Albert and his brothers weren’t on their passport the Gestapo turned them away at the border. “I was lucky to come to England, and even luckier not to go to Poland,” said Albert.

Aged 11, he’d had to change to an all-Jewish school. “We used to go to a swimming pool, then a sign went up saying, ‘Dogs and Jews Not Allowed’,” Albert recalled in his memoir, compiled by his friend Tamar Yellin.

His two older brothers were in Palestine and his younger brother was hidden on a farm in France when Albert’s mother put him on a train to Cologne in February 1939. He joined youngsters travelling to Harwich, Essex, then to a holiday camp in Dovercourt, Kent, housing 2,000 children. Most would never see their families again. Many of them were traumatised, but Albert saw it as an adventure. “I was pleased to leave Germany, it was my only chance of escape, and excited to go to England,” he said.

Soon he was chosen by Mrs Stroud as one of 24 boys aged 14-16 for the Bradford hostel. They went to Drummond School to learn English, then were forbidden to speak German. Albert recalled daily life at the hostel; pillow fights, card games, cricket, going to the cinema to see King Kong and collecting bluebells in Heaton Woods for Mr Stroud’s mother, “a prolific sock-mender” at the hostel. “Mr Stroud visited every Sunday to check how it was being run,” said Albert. “He arranged that we boys could go to the Odeon on Manchester Road for free once a month. Once Mr Stroud took me out to his farm in his Rolls Royce. I said to myself, ‘If I can ever afford it I will buy myself a Rolls Royce’. Eventually I did.”

Three months after arriving at the hostel Albert was sent to work at Bloch and Adler comb factory. He later landed an engineer apprenticeship at Coward Brothers. Opening a Post Office account with seven shillings, he later recalled: “My bank book was the book that changed my life.”

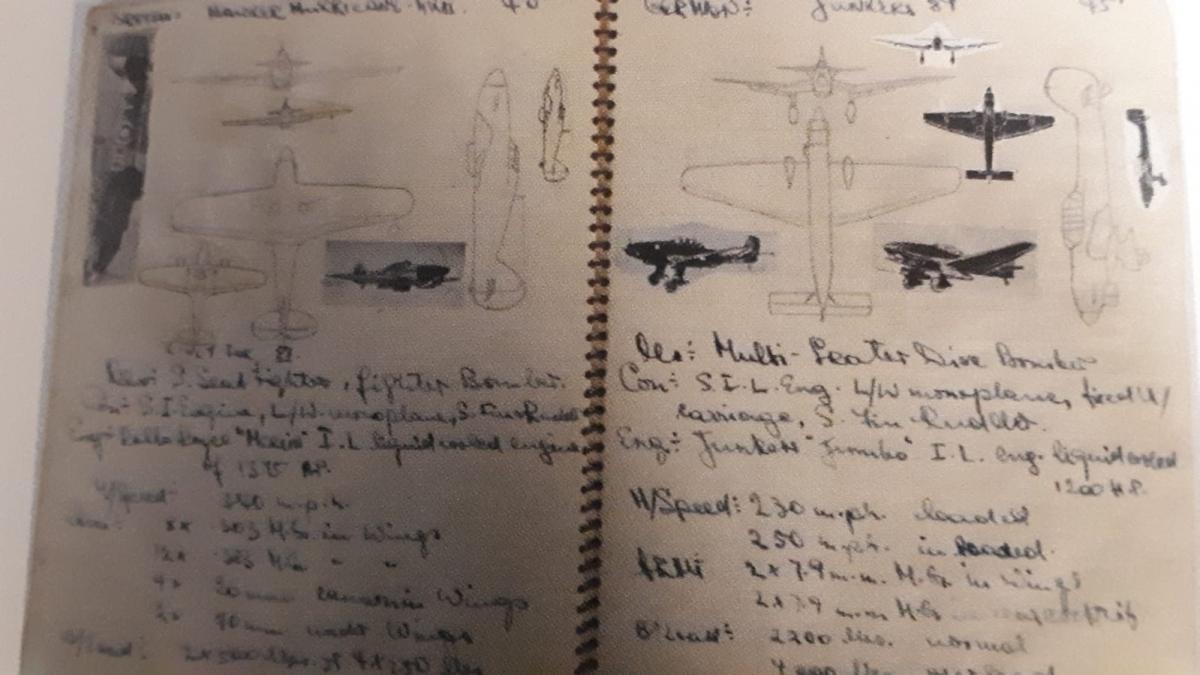

When he turned 18 Albert, born in France and a Polish national, was allowed to join the RAF. Training as a fighter pilot, he spent the rest of the war in South Africa. “Our unit was surplus to requirements, I never did see action,” he said.

While in South Africa, he heard that his parents were alive. Escaping to France, they’d been hiding in a Paris flat. “My mother didn’t set foot outside for three years. The concierge used to bring them food,” he said.

Albert was reunited with his family in Paris - he was the only boy from Bradford’s Jewish Refugee Hostel whose parents survived the Holocaust. When the war ended he was an interpreter at a prisoner-of-war camp near Peterborough, then joined his parents back in Saarbrucken where they’d set up a cloth business. On a buying trip to Bradford in 1949, he stayed at the Manningham hostel he’d called home - now a hotel, run by the couple who were the hostel wardens. One evening, invited by their daughter to a party, he met Lilly Sobol, and three weeks later they were engaged. Albert moved back to Bradford and they married the following year. The couple, who lived in Nab Wood, had three children and later two grandsons and a great grandaughter.

Returning to Bradford, Albert had studied at the Technical College to learn the wool trade. He later took over his father-in-law’s mill and in 1958 started a textile business, A Waxman (Fibres) Ltd, in Manningham. He acquired three mills in Denholme and bought and expanded Sobol’s mill in Elland. As Waxman Ceramics, his company became one of the UK’s leading distributors of tiles and mosaic.

Albert was President of Shipley Golf Club, the Bradford Jewish Benevolent Society and Bradford Club. In 1989, 50 years after coming to the Parkfield Road hostel, he tracked the other boys down for a reunion there (it was then the Carlton Hotel), filmed for BBC documentary Bradford Kindertransport. “Some men were emotionally scarred by what happened to them and their families. They had never talked about it, not even to their wives, “ Albert told the T&A. “We never forgot the kindness of Bradford, not just the Jewish community, but the Quakers and Salvation Army.”

Aged eight, Lilly came here from Leipzig in 1938. Her parents were interned on the Isle of Man and she and her sister went to boarding school in Ilkley. “English people were so friendly,” she recalls. “We went back to Leipzig after the war. The things we’d had to leave behind had been auctioned. The words ‘Heil Hitler’ were stamped on them.”

Now 90, Lilly believes Albert’s success, in the business world and local community, stems partly from his time in the hostel: “He had a great determination there to make a success of his life.”

Rudi Leavor, chairman of Bradford Tree of Life Synagogue, whose family befriended Albert as a boy, said: “The hostel saved 24 boys and the wardens’ lives and turned out to be a very happy place of sanctuary.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel