“YOU jump out the plane, everything’s covered in smoke. You see explosions where you’re going to land. All this passes by in a flash because as soon as you’re over the DZ the light goes on and out you go, jumping from 450 feet so really you’re in the air 16, 17 seconds. The lads who jumped at Arnhem, at least 50 per cent had never fired a shot before. I joined the Parachute Regiment in North Africa early ‘43, I’d been through it before. But these young lads, to fly into that chaos with lads falling down right and left...”

These are the words of 100-year-old Victor Gregg, who was with the 10th Parachute Regiment when he jumped over Arnhem on September 18, 1944. “It was chaos,” he recalls. “The lads were dropping on the bodies of those who’d dropped before. The DZ (drop zone) at Ginkel Heath was littered with dead bodies, almost as many Germans as British.”

Victor’s memories are captured in a sound archive compiled by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, marking the 75th anniversary of some of the most significant battles in history. Earlier this year the CWGC launched its Voices of Liberation Campaign, calling on people to share stories of turning points of the Second World War. Exploring the conflict from the beaches of Normandy to the mountains of Manipur, the online resource features firsthand accounts from veterans and of family pilgrimages to battlefield sites and war cemeteries. The aim, says the CWGC, is to “capture stories of those who fought in these battles, the memories we hold of those who died and what it means to look back on their sacrifice”.

Today, Remembrance Sunday, we mark the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Arnhem and the liberation of Europe. As well as reflecting on wartime experiences, the CWGC’s recorded interviews highlight what its cemeteries and memorials across Europe, the Mediterranean and the Far East mean to veterans and families today.

Andrew Fetherston, CWGC Chief Archivist, is appealing for Bradford veterans and families to get involved: “We want people to share their connections to the war and our cemeteries to ensure that as Commonwealth nations we have not forgotten their sacrifice.”

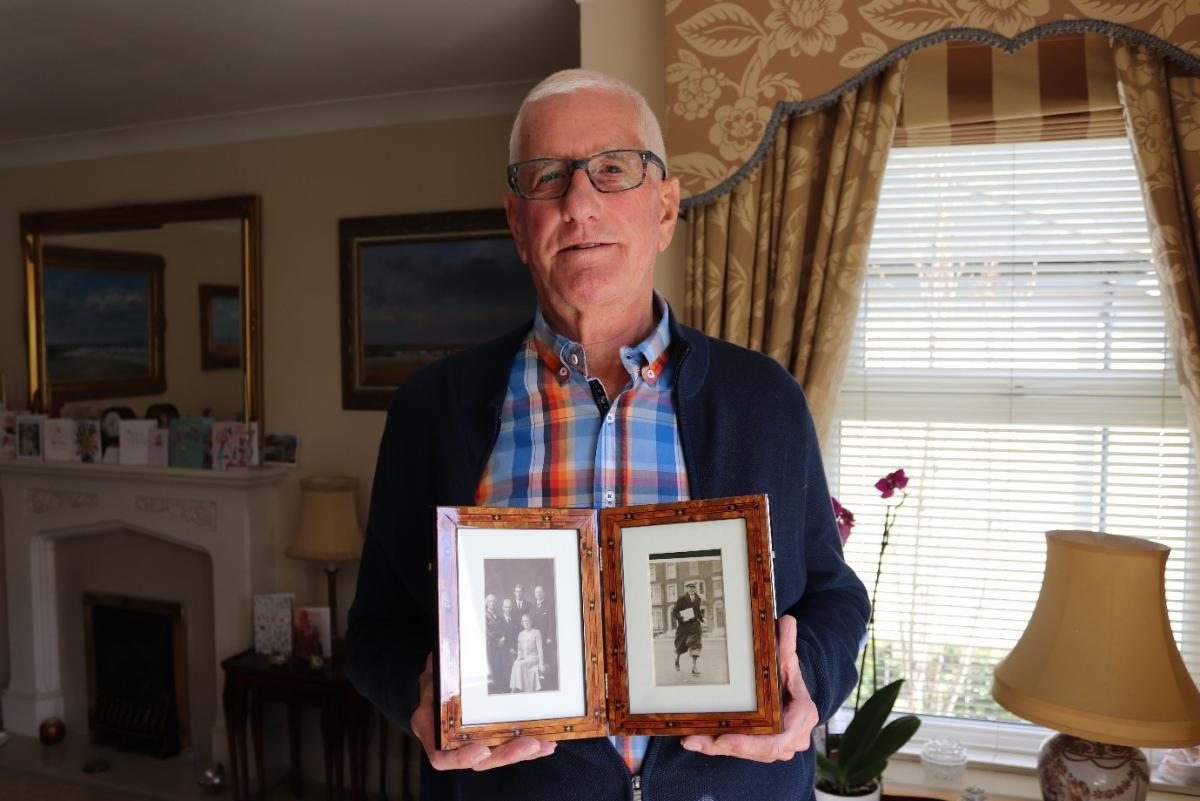

Alan Gaurdern was born on June 6, 1944 and never met his father, William, who died in Normandy on July 11, 1944. The sound archive includes Alan reading the last letter his father wrote to his mother, days before his death: “My Dearest Ethel, You know we’ve faced up to the likelihood I may not come back...We’ve had a perfect married life together haven’t we? But if I don’t come back I want you know how much I thank you for our lovely life, and to let you know it isn’t my wish that you remain a widow. I hope we can sit down one day and laugh at what I’ve written. Wish me a happy landings and be a brave lass, you’re not to worry or the milk will go sour.”

Of visiting his father’s grave in France, Alan says: “It’s a moving experience to visit these wonderfully kept war cemeteries. Everybody at some point in their lives should visit such a place...to see the result of the carnage and the way the Commission cares for them.”

Jim Hooper served with the Glider Pilot Regiment 1942-46. Now 97, he says of Arnhem: “It was a relief to us biting our nails waiting to get to the action. Most of us felt ‘It’s going to be a bit of a doddle because the Germans are in retreat. We’ll be more of an occupation force than anything else’. The powers-that-be knew that wasn’t the situation. But our attitude was: ‘At least we’ll see some action’.

“We got into Oosterbeek en route to Arnhem to a rapturous welcome from local people. Yards from the railway station, we were halted by fire. We were pretty well out of ammunition. Three Germans were just about to throw stick grenades, at that point I surrendered along with the others. We were marched to the outskirts of Arnhem and shipped by cattle wagon to Germany.

“Personally, and I think others felt the same way, I couldn’t believe how friendly the Dutch people were. They greeted us with euphoria and suffered terribly as a result, I couldn’t understand how they could be so generous in spirit. They said: ‘It’s simple - you gave us hope. When you came we knew freedom would not be far away’.”

A member of the 1st Airborne Division, Les Ransom was one of the few who made it to the bridge at Arnhem, holding it for four days. Les was sent to a PoW camp in Germany and later put to work at a tramway repair depot in Dresden during the 1945 Allied bombing of the city. Of his capture, Les, 97, says: “We were surrounded, all the houses were on fire. We had no ammunition and hadn’t eaten anything since coming off the plane. We smashed valves on the radiators and drunk the water. Germans were going round shooting down passageways, I decided it was time we packed it in. We put our hands up.”

Recalling the heavy Dresden bombings, he says: “We were in the shelter, when we came up in the morning a bomb had dropped near the window. If it had gone off we’d have been buried. The Germans said they’d march us to a demarcation line and hand us over to the Allies. We set off and the first night stopped in a barn. Three of us we were so fed up we walked off. This German shouts: ‘Come back or I’ll shoot!’ I said: ‘Shoot then! I couldn’t care less’ and we kept walking. Course we got recaptured. They were alright, they gave us a big supper.”

Adds Les: “Arnhem was a beautiful town. When we left it was nowt but a heap of rubble. Our lot, there were three platoons went, about 63 men, and 49 were killed. I go to the cemetery at Oosterbeek, I walk around and see ‘em, those blokes I served with in North Africa and Italy, killed at Arnhem.”

Eric Richards, 93, fought in the Sonnenberg area for nine days before the call to evacuate. Shot in the leg, he and many other wounded Allied soldiers, surrendered. He spent the rest of the war a PoW in Germany, near Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. “We got our ‘chutes on and took off to Ginkel Heath. We never got into Arnhem. It was bucketing with rain, we got called in to wrap material around our boots because we were going to cross the river. At 10pm the whisper came: we’re moving. A machine gun opened up, I got hit in the leg. In the morning, first time we saw the river, we went into a house full of wounded left behind. The Germans, 9 Panzer, SS, came up with a tank. A wounded glider pilot in the house went out with a white flag. As we filed out the German officer brought his men to attention and saluted us - military salute, not the Nazi salute.”

While being shot at by a sniper during the battle, Eric had climbed a tree and dropped his fighting knife. “Forty years later I’m at Arnhem with my wife. I went to the battle area and said to the gardener: ‘You see that oak tree? I dropped my fighting knife there’. Two years later I was there again. He said: ‘I found your knife while planting some rose bushes’. The blade was rusted, that knife is now in the Royal Engineers museum at Chatham.”

On June 6, 1944 - D-Day - Donald Hunter was an 18-year-old radio officer with the Merchant Navy taking troops and equipment to Normandy beaches across the Channel. “An old Merchant Navy ship was bringing bodies back in black bags, they were laying them on the deck. They were called coffin ships. That was quite a blow for a young man; troops going in, coming out, dead bodies. I see it vividly,” says Donald, 93. “I’ve visited all the war cemeteries in Normandy. Heartbreaking to see elderly men, tears streaming down when they found one of their comrades buried. It brings home to you, all the graves. You see stretches of white stone, and the real price of war.”

l For more about the CWGC archive email voicesofliberation@cwgc.org or go to liberation.cwgc.org

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here