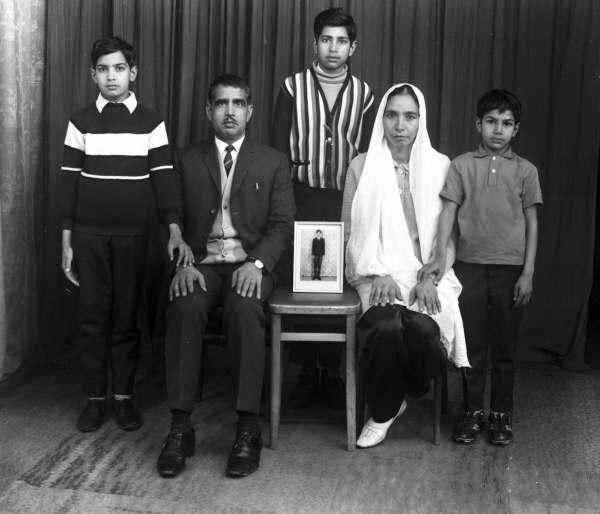

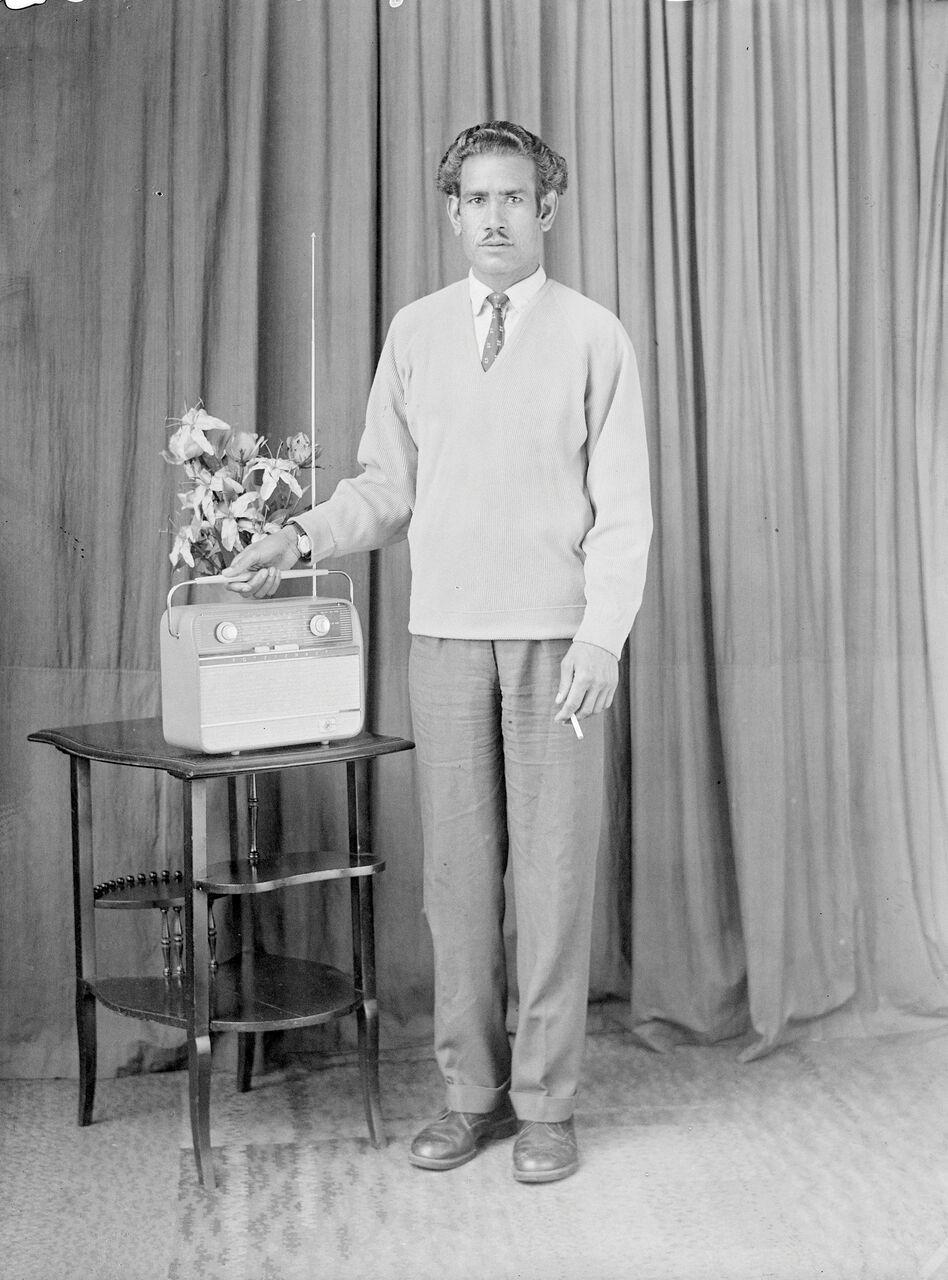

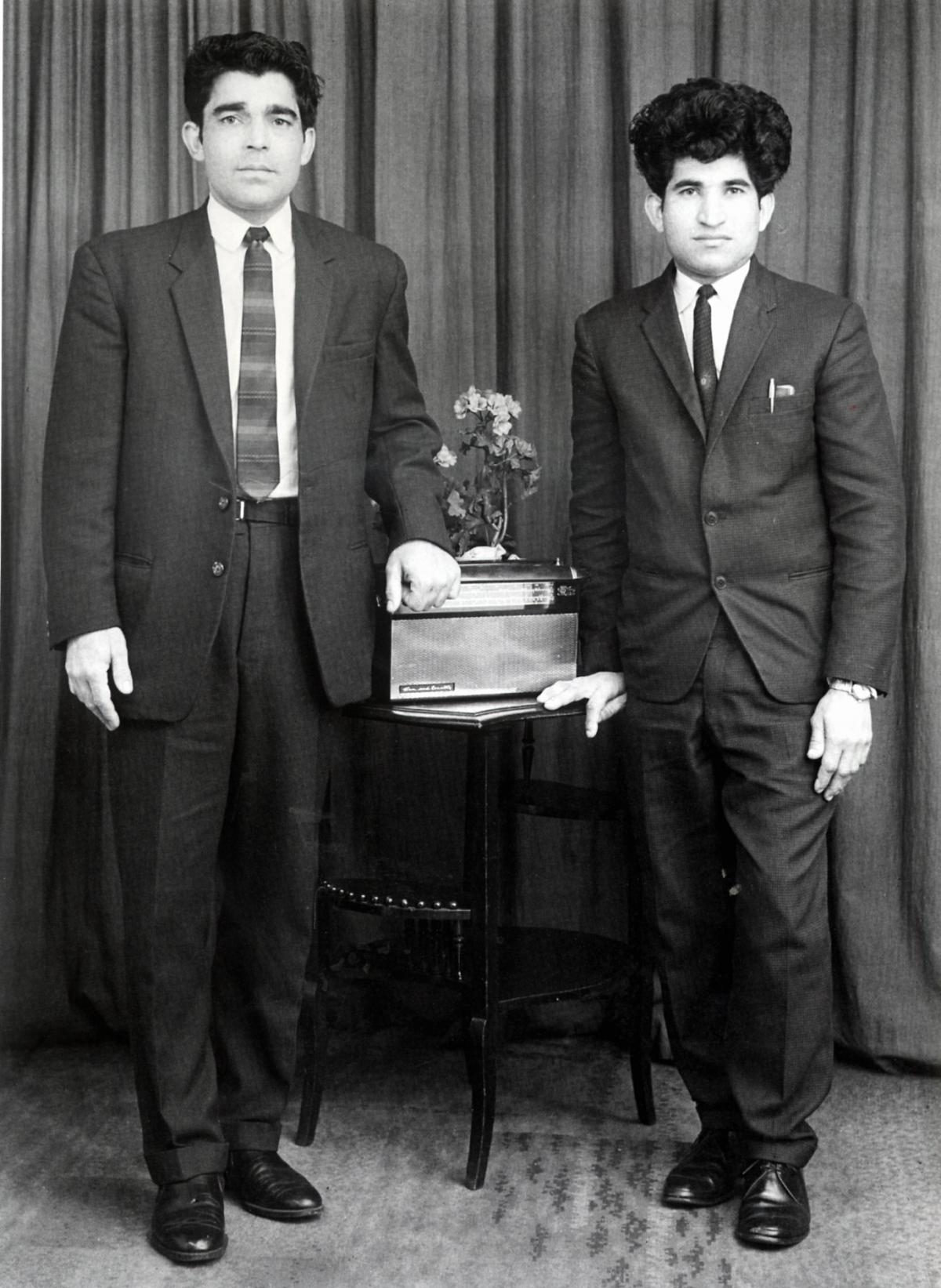

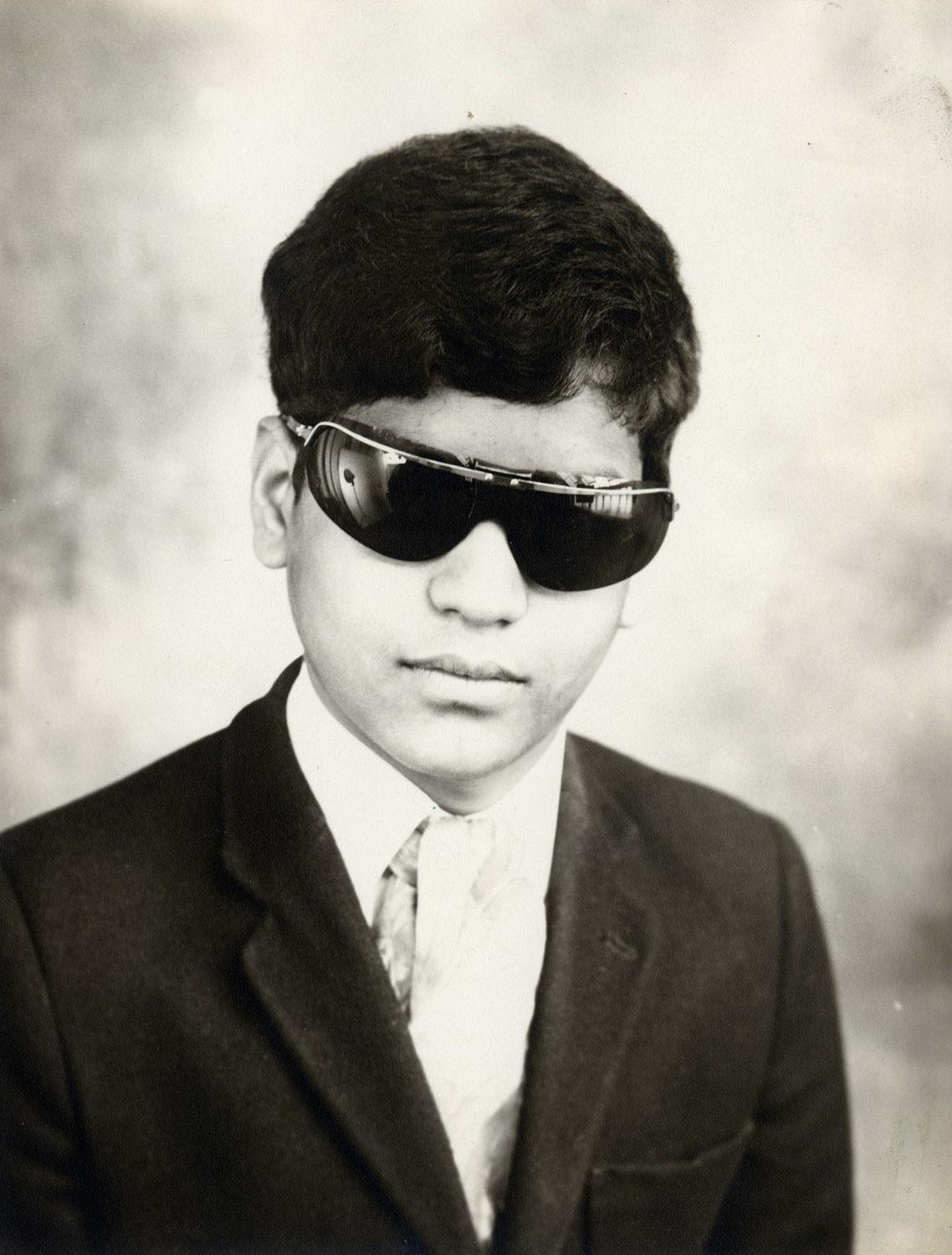

DRESSED in smart suits and shiny shoes, standing to attention against a heavy curtain backdrop, generations of people posed for the camera at Bradford’s Belle Vue Studio.

The photographic studio, on Manningham Lane, was popular with new arrivals from the South Asian subcontinent, the Caribbean and Eastern Europe, who settled in Bradford to work in mills. The formal portraits were often sent back to relatives in countries they’d left behind.

When the studio closed in 1975, thousands of its photographs were saved from a skip. The portraits, dating back to the early 1900s, were all taken on the same camera, and record the changing face of 20th century Bradford.

Now this remarkable collection of images is the focus of a BBC Four documentary, Hidden History - The Lost Portraits of Bradford.“From a single Victorian glass plate camera in one back room, this studio told the story of extraordinary post-war changes,” said Bradford photographer Tim Smith, who appears in the programme.

Belle Vue Studio was established in 1902 by Benjamin Sandford Taylor. After he died in 1953, his assistant Tony Walker took over. “There were dozens of these studios in Bradford, up to the Second World War,” said Tim. “Post-war, lots of people started to own new hand-held cameras so most high street studios closed. Belle Vue managed to survive partly because of its location and partly because Tony welcomed newly-arrived migrants. From the 1950s-70s Belle Vue Studio was widely used by these communities. People from India, Pakistan, the Caribbean and Eastern Europe were used to formal Victorian-style photography because that style of studio portraiture had been exported around the world.

“All the Belle Vue portraits were taken on a single camera in a single spot in the studio, which never moved in 50 years. Tony continued using daylight, and the same backdrop, until 1975. Nothing changed in the studio - but outside, the city was transforming city, and he recorded that through these portraits.”

Tony Walker closed the studio in 1975 when his wife was ill. “I interviewed him a couple of times, he’d planned to re-open the studio but when his wife died his heart wasn’t in it,” said Tim.

Thousands of negatives lay forgotten in a cellar until the 1980s when Tony came to empty the building and started throwing the archive out. The negatives would have ended up in a skip were it not for the man who was buying the building, who spotted them and contacted Tim at the Bradford Heritage Recording Unit.

“I was expecting endless pictures of weddings and babies on rugs, but he brought a couple of dozen along and I thought, ‘Wow, these are extraordinary’,” said Tim. “Not only are they are a record of these migrant people, they’re beautiful pictures. There’s a stillness about them, a timeless quality.”

Around 17,000 of the negatives were saved and stored in Bradford Museums and Galleries archives.

The images reveal a fascinating snapshot of life for people settling in Bradford from across the world. Props provided by the studio were displayed as visible signs of success. A briefcase hinted at white collar aspiration, a book showed off an education, rows of pens in a pocket signified a clerical job, watches were pulled low on wrists. Tony had an arrangement with a gentlemen’s outfitter to borrow suits. Asian and Caribbean bus drivers were photographed in their uniforms. “The message to loved ones was ‘I’ve arrived!’ They showed the best of themselves, which is what everyone does in photos. It was the Instagram of its day,” said Tim. “These pictures are a moving reminder of the dreams and aspirations that brought people to Bradford. But the studio and its props had long been used locally; mill girls often posed with fur stoles.”

Working with Tim and Bradford museums staff, presenter Shanaz Gulzar identified and tracked down people in the portraits for the documentary. “We held pop-up exhibitions at Windrush events and places like Bradford’s Ukrainian Club. People recognised themselves as children, it was very emotional,” said Tim.

Bradford Museums and Galleries and the National Science and Media Museum have teamed up to digitise the images. A re-creation of Belle Vue Studio is planned at the Media Museum next spring. “I’ve been fascinated by the people in these pictures since 1986, I’m delighted they’re now being shared with a wider audience,” said Tim. “The old Belle Vue Studio is now Al-Mumin bookshop. I took a BBC researcher there, a young man behind the counter showed us a photo of his parents, taken when they arrived in the UK. He thought it was a London studio, when I told him it was taken in a back room at that very shop he was gobsmacked.”

l Hidden History BBC 4, Mon, 9pm.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel