JACK Firth was barely out of St Bede’s Grammar School when he found himself working as a spy at the tense frontline of the Cold War.

Aged 19, he was on top of a ‘listening tower’, dangerously close to Soviet-occupied East Berlin, translating Russian military operations in the dark of night. “I didn’t feel safe, but I had a job to do” he says, recalling the rumble of nearby tanks blowing in on the east wind.

Jack, from Low Moor, was called up for National Service in March, 1956 and chose the RAF, on his father’s advice. He went to RAF Bridgnorth for basic training and, while other conscripts took on roles of drivers, cooks and clerks, Jack spotted a Russian language course and applied. “I liked languages at school; French, German and Latin,” he says.

Initially he heard nothing and was sent on a clerical course - “learning how to fill in forms and write polite letters to Commanding Officers” - then, two weeks later, he was handed a travel warrant to Scotland, where he was to train to be a Russian linguist.

Jack spent eight months at JSSL Crail, a former naval air station on the Fife Coast. Founded in 1951, the Joint Services School for Linguists (JSSL) trained selected National Service conscripts in languages, mainly Russian. The aim was for them to listen in on and interpret Soviet military communications. Among the conscripts at Crail were a young Alan Bennett, Jack Rosenthal and Dennis Potter, all learning Russian.

Like them, Jack was taught by a colourful mix of aristocracy, professors and Soviet defectors. He recalls princes and countesses with gold rings and gold-topped canes.“They were mainly Eastern European people who’d escaped the Russians after the war. One teacher, Lydia Matvenna Daniloshkina, was a teenager during the Russian Revolution. It was living history,” says Jack. “They’d had to work for two years in industry over here - one or two had been in Yorkshire mills, so they understood my northern accent.”

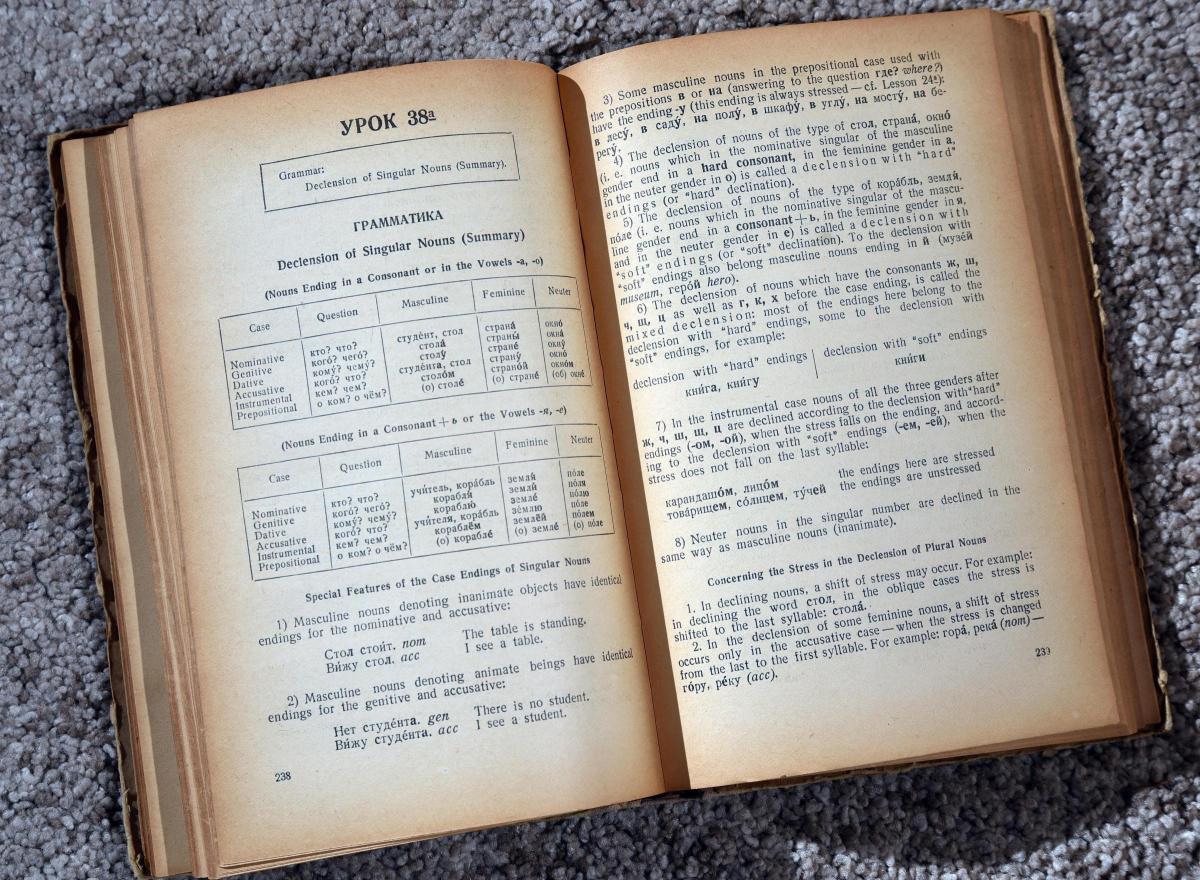

For Jack JSSL Crail was “like going back to school”. He took to Russian lessons well. “Once I’d learned the alphabet I was okay, then we were taught grammar,” he says. “Numerals were important, for taking down the height and speed of aircraft.”

Not that Jack knew this at the time. “We were told nothing at Crail,” he says. “It wasn’t until later on that we really got to know about the job we were going to do.”

On completing the course at Crail, Jack was posted to RAF Wythall, near Birmingham, for radio training. Learning he was to be a spy, he signed the Official Secrets Act. “I was told never to speak about it, and I never did,” he says.

After six weeks he was put on a train to London, then a ship at Harwich for an overnight crossing to the Hook of Holland. “Exciting for a lad of 19 - I’d never even been out of Yorkshire,” he says.

His first sight of a Russian uniform was on the train journey to Berlin: “I’d fallen asleep and when I woke up the train had stopped on the East German border. I looked out of the window and saw a British officer handing over documents to a Russian. The train was there for ages. Were the Russians taking note of our details? It was very still and eerie, I felt uncomfortable.”

Arriving at Berlin, Jack was transferred to RAF Gatow, an intelligence gathering centre. From 1957-58 Jack worked in a concrete building filled with rows of radio receiver sets. Armed with a pencil and piles of paper, he and around 20 other young National Servicemen meticulously translated details of Russian air traffic and ground movements. The information was then flown to London to be de-coded.

It is only recently that JSSL files have been declassified. For nearly 60 years, Jack kept his undercover work a secret. “I guessed what he was doing, but he never told me,” says Audrey, his wife of 62 years.

Now 82, Jack says: “If I said anything, I could be sent to prison - I was very much aware of that. In Berlin, we only knew what we needed to know. It wasn’t until later on that I learned the importance of what we did.”

Speaking to Jack at his Queensbury home, it is clear how much that work meant to him. He still has his Russian grammar books from Crail, and has fond memories of friends he made in Berlin.

But there was, he says, constant tension: “At times we felt unsafe.The Russians had tanks and could’ve swept in at any time. We had the Army on our station but we were told if the Russians took over there was nothing they could do.”

After the 1945 separation of Germany, Berlin was divided into four sectors, occupied by the British, US, French and Soviet. As the East-West divide hardened into the Cold War, the city became East and West Berlin. Jack found himself uncomfortably close to Soviet-controlled East Berlin.

He recalls night shifts in the Direction Finding Tower: “I’d cycle to an airfield, and a tower with an aerial sticking out of the roof. I used a ‘direction finder; turning a disc with an aerial. It was very close to the Soviet sector. On the other side of the fence was a Russian tank testing station; when the east wind blew on cold winter nights you could hear engines rumbling in the dark. I worked there from 5-11pm, then I was straight down that scaffolding and back on my bike!”

He adds: “We were left to get on with the job. We gathered information to build up a picture of the Soviet airforce. Our notes were driven to an airport, in a diplomatic bag, and flown to London, then to GCHQ in Cheltenham for de-coding.”

Jack worked a three-day cycle - “five hours, 10 hours then a day off, over a weekend, then a week of nights” - and leisure time was often spent in American and French sectors. “The Russian sector was forbidden but this was pre-Berlin Wall, and some of the lads sneaked in,” he says.

When Audrey, Jack’s then fiancee, decided to visit him, she discovered her own safety was at risk. “The authorities wouldn’t let me go on a train, because of Jack’s work, so they arranged for me to fly, with a visa,” says Audrey, who stayed in Berlin five days at Christmas. Jack took her to the French sector. “They had nice bars, with telephones on the tables,” says Audrey.

Adds Jack: “The French club’s food was better than our meat pie. They had caviar and steak. The US sector had French fries.”

Each sector had bars and cinemas, and Jack played cricket against army teams at Gatow. “They didn’t like being beaten by the RAF,” he smiles.

By 1959, with the onset of spy satellites, the JSSL ceased training. The “spy school” in Crail is now a farm, and RAF Gatow a Luftwaffe base. In 1958 Jack returned to Bradford, where he’d married Audrey the previous year, while on leave. The couple lived in Wibsey and had three children. Today they’re great-grandparents.

Next month, on Remembrance Sunday, a group of ex-linguists will march, with the RAFLing Association, to London’s Cenotaph. Like Jack, they were the youths who, armed with pencils, played a vital role in national security.

After he was de-mobbed Jack worked at Bowling Mills for 35 years. These days his Russian is “a bit rusty”, but he says: “I will never forget my time as a teenage spy.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here