IT was a chilly Saturday morning in 1858 when a delivery of peppermints landed at a stall in Bradford’s Green Market.

By the end of the weekend the city was mourning the deaths of 20 children, with 200 more people seriously ill.

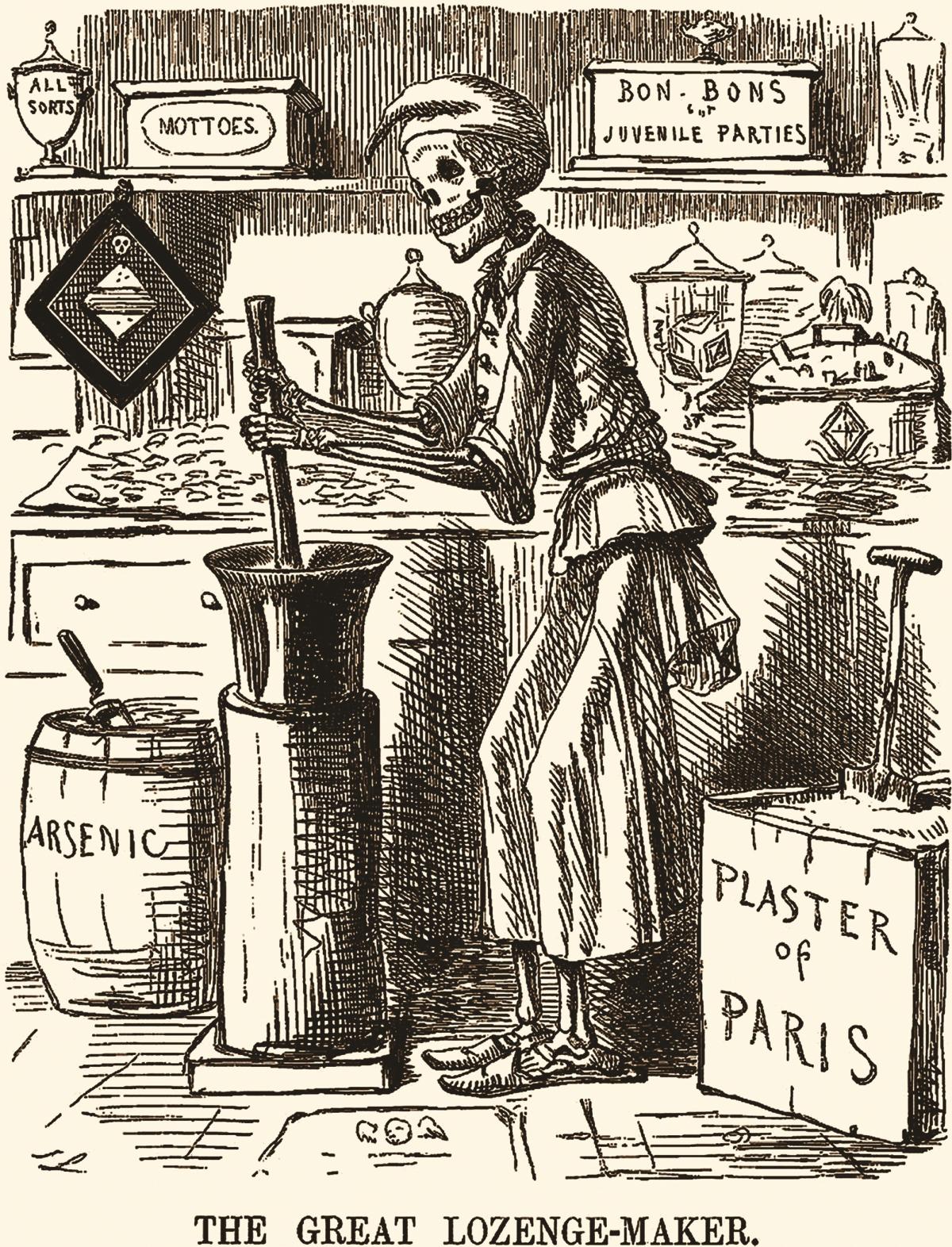

But this was no deadly Victorian disease - it was all down to the peppermints, inadvertently laced with arsenic and sold by the bagful. A dreadful mistake meant arsenic trioxide was added to the sweet mixture, instead of a cheap sugar substitute.

The sweet stall was run by William Hardaker, ‘Humbug Billy’, who bought his produce from wholesale confectioner Joseph Neal. Operating from premises in Stone Street, Neal used a substance known as ‘daff’, made from plaster of Paris, powdered limestone and sulphate of lime, widely used in confectionery.

On Monday, October 18, Neal sent one of his workers to Charles Hodgson, a druggist in Baildon Bridge, to purchase 12lbs of daff. On arrival he learned Hodgson was ill and a man called William Goddard was standing in for him. Goddard consulted Hodgson, who said the sweet maker would have to wait for the daff until he was back at work. When Neal’s worker insisted on being served, Hodgson reluctantly told Goddard where he could find the daff - but 12lbs of arsenic was sold instead. Both white powder substances were stored side by side, neither labelled correctly.

The poison ended up in humbugs made by James Appleton, a sweet-maker employed by Neal. Appleton said they seemed a little darker than usual, but Neal dismissed his concern and 40lbs of the lethal sweets were delivered to Humbug Billy’s stall on a busy market day. Sold at three halfpennies for two ounces, 5lbs of them were sold before the market closed.

Very quickly two young boys died, and many people were afflicted with sickness, diarrhoea and intense abdomen pain. It was thought at first they had cholera, but soon arsenic was established as the cause, traced to Hardaker’s stall. Each lozenge contained enough poison to kill two people, and if it wasn’t for the authorities quickly administering antidotes many more people would have died. Bell-ringers worked through the night and the city was covered with warning posters.

Goddard, Hodgson and Neal were charged with manslaughter but the trial was later dropped. The poisonings did, however, lead to new legislation on food production, and the sale of poisons.

The Bradford sweet poisoning is one of the strange and spooky incidents in Illustrated Tales of Yorkshire, by historian David Paul. David’s curious, quaint and mysterious tales from Yorkshire’s wolds, dales and moors, from its coast to towns, cities and villages, are accompanied by his photographs of places featured.

A book of strange tales of Yorkshire wouldn’t be complete without a chapter or two devoted to York. In this book you’ll find ghostly sightings at Micklegate and St Mary’s Abbey in York, haunted by Sister Hylda, a 13th century nun “dishonoured, ruined and murdered” by a man of cloth.

Closer to home, a chapter called Hell’s Bell takes us to Soothill, Batley, in the late 18th century, where an iron foundry master, in a rage, threw a young apprentice into a white-hot furnace. His somewhat lenient sentence was to provide a new bell for the steeple, but whenever he placed iron on the furnace the fire, weirdly, went out. After months of this he built another furnace... but couldn’t extinguish it. What gruesome fate awaited the foundry master when the bell was finally installed in the steeple?

Why did two lovestruck brothers end up in the hands of a Whitby press gang? Why does a howling hound haunt lead mines in Mossdale? Why were two security guards on patrol during construction of the Stocksbridge bypass, in 1987, left terrified at the sight of laughing children?

And why did the river rise in Semerwater, an isolated Wensleydale spot, covering the entire village but halting just before the cottage of an old couple? It is said the roofs and chimneys of houses can sometimes be seen below the water - a tributary of the River Ure near Aysgarth Force - and the muffled bell of the old church is heard in stormy weather.

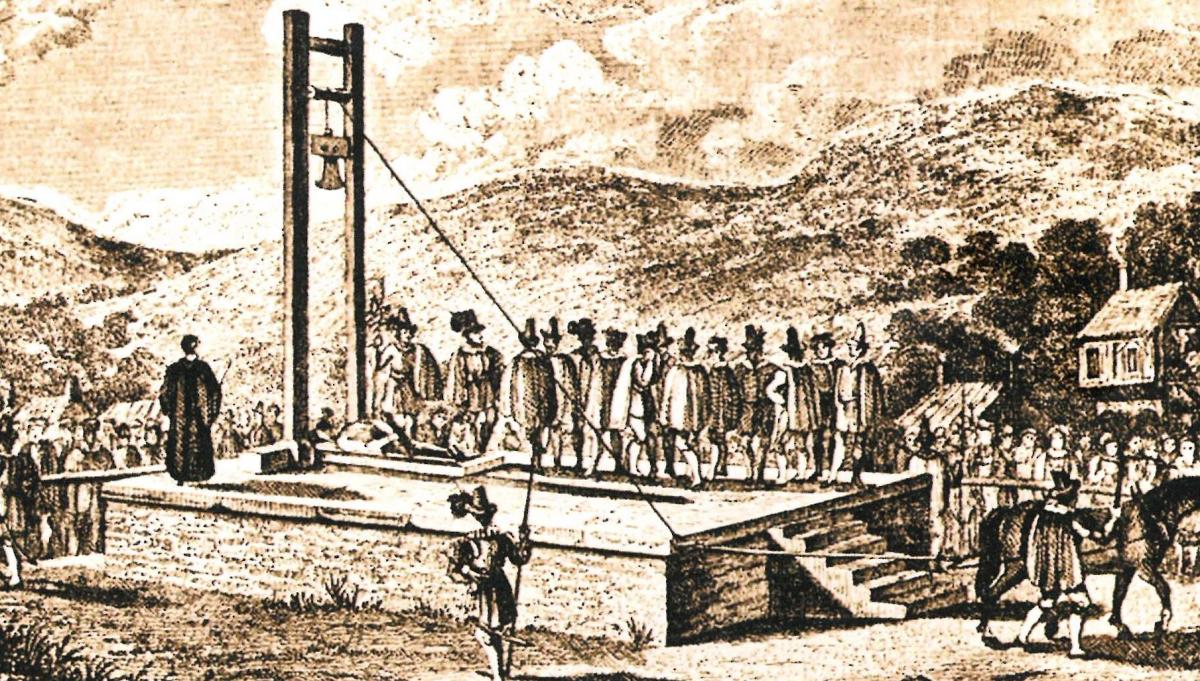

There is, writes David, an old saying in Yorkshire: ‘From Hell, Hull and Halifax, good Lord deliver us’. Halifax, with its mighty Piece Hall, had its own way of punishing thieves stealing cloth - they were instantly beheaded. The Halifax Gibbet can be traced back to Norman times, and the town’s parish register contains a list of 49 people who lost their lives to it, from the first execution on March 20, 1541.

Colourful characters highlighted in the book include Ursula Sontheil - born to an unmarried 15-year-old mother in a cave on the banks of the River Nidd, and later known as Old Mother Shipton - and William Bradley, the ‘Yorkshire Giant’, who, at 7ft 9ins was the tallest Englishman ever recorded. Born in the East Riding in 1787, weighing 14lbs, he towered over his classmates at school and went on to be a star attraction at Barnum’s circus.

l Illustrated Tales of Yorkshire, by Amberley Publishing, priced £14.99.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel