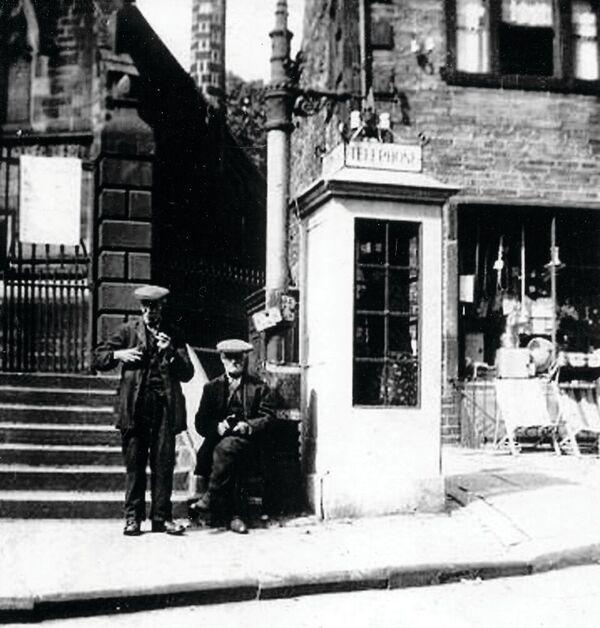

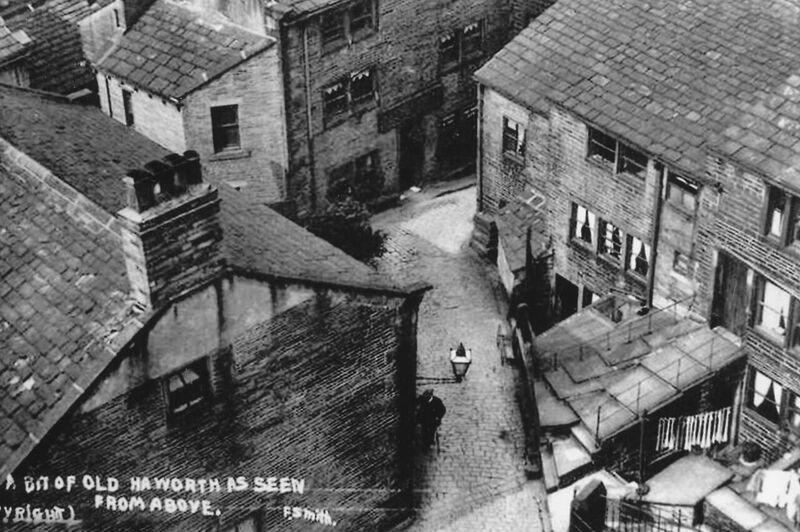

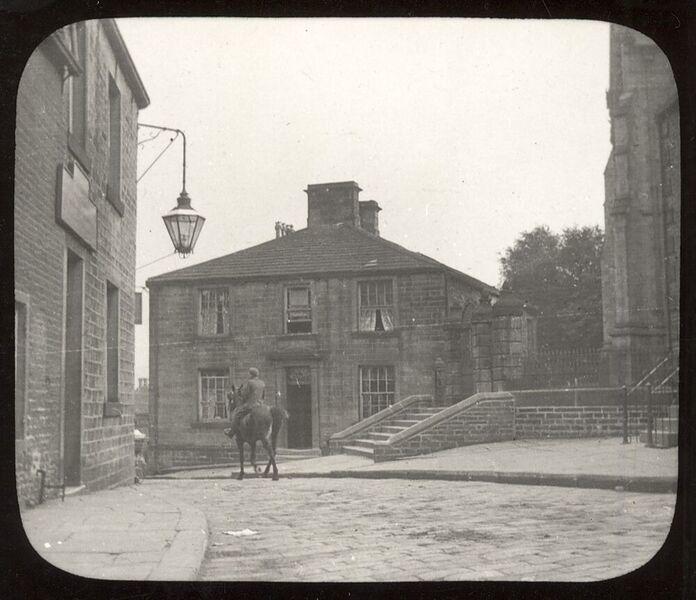

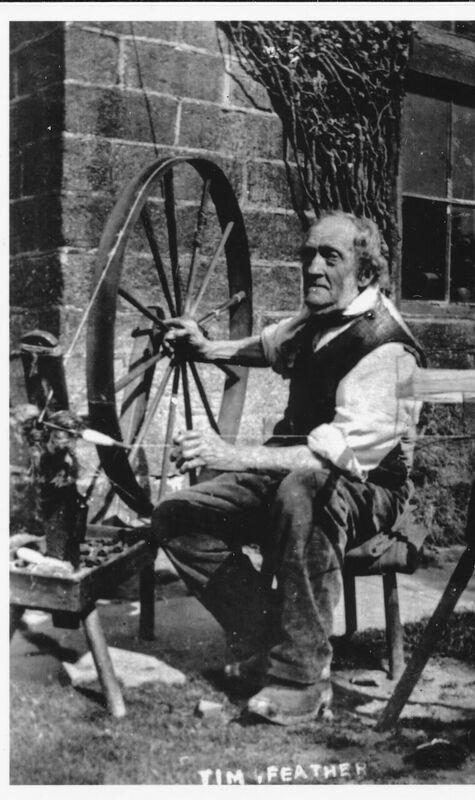

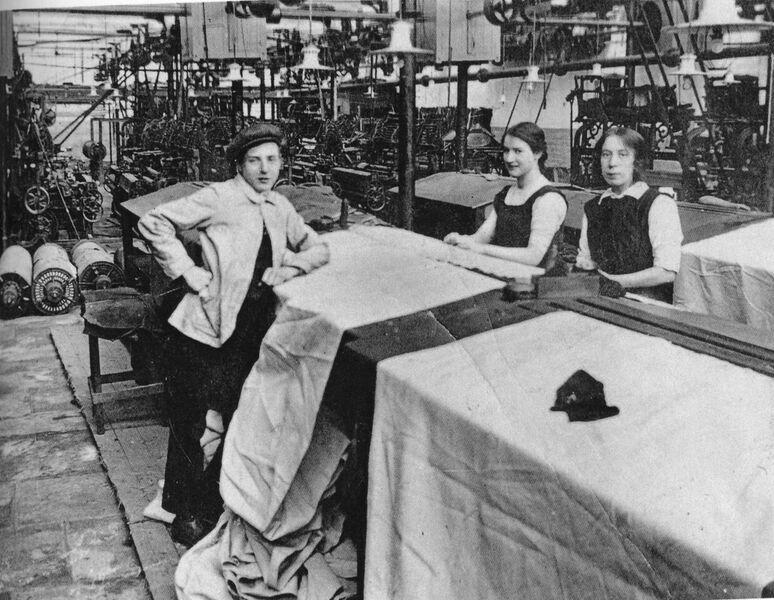

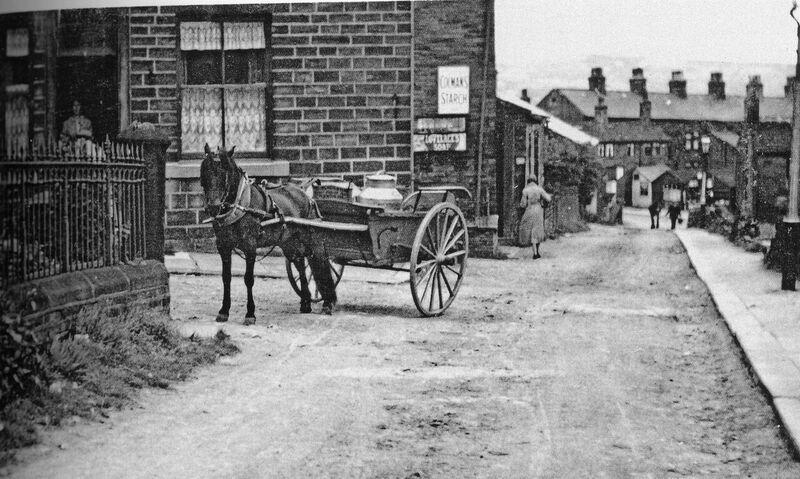

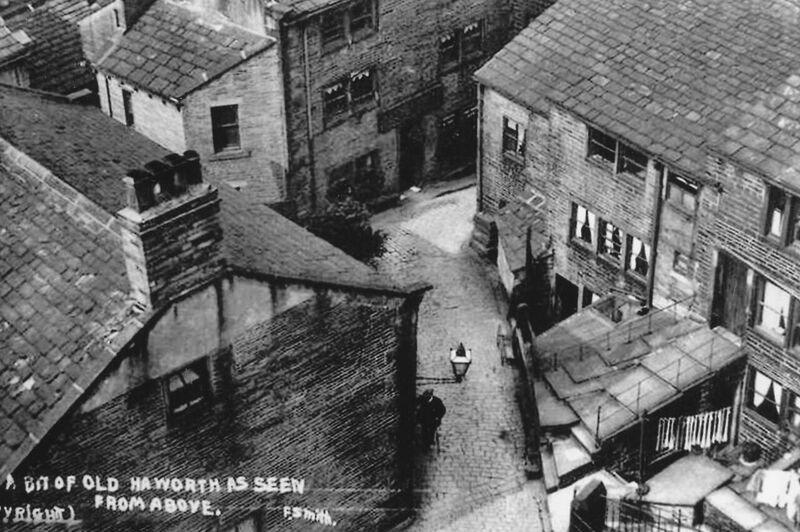

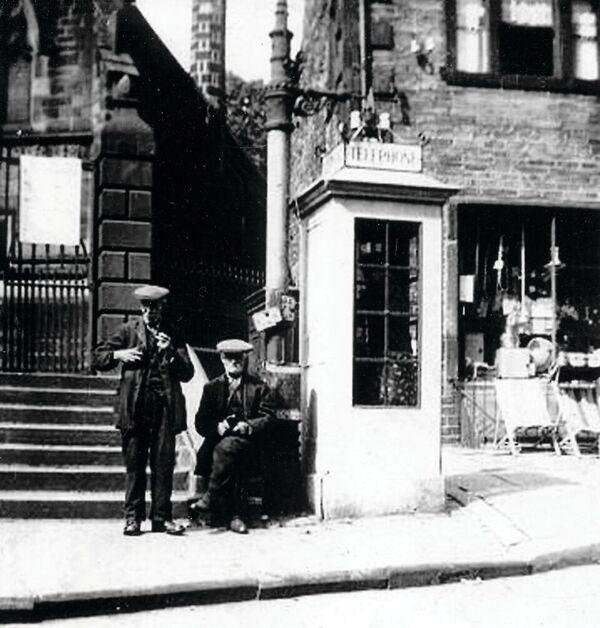

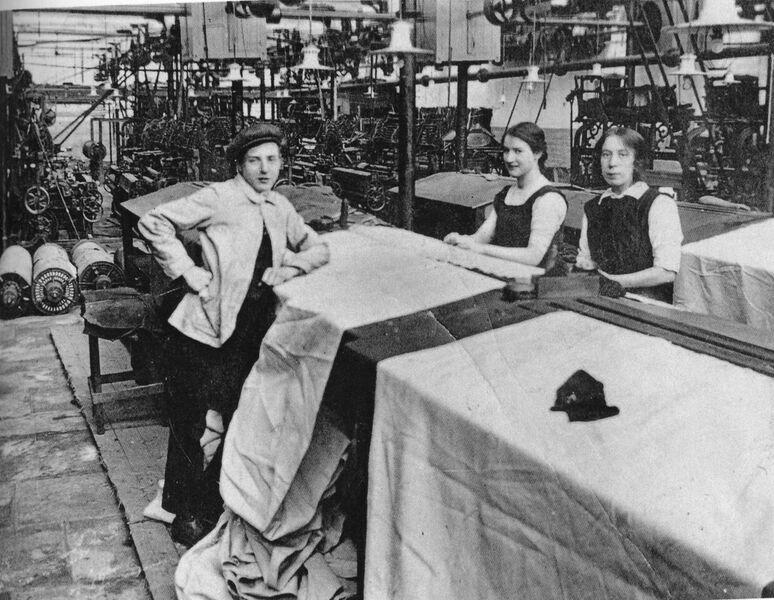

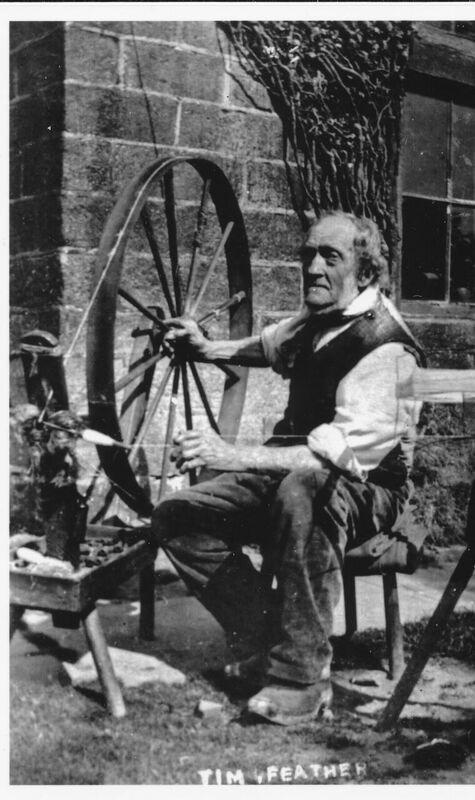

A HORSE stands patiently waiting on a street corner, its cart pulling a milk churn. Two flat-capped old men, one puffing on a pipe, pass the time in a sunny spot beside a telephone box. Three young workers pause to smile for the camera in a weaving shed.

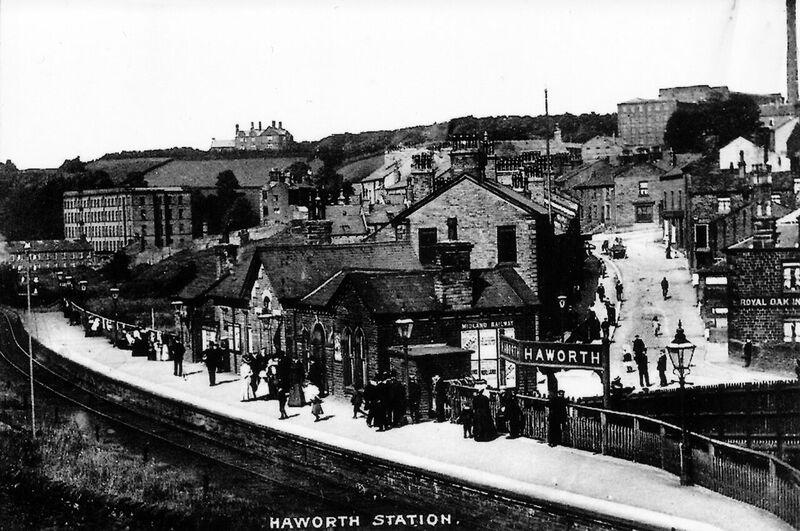

These evocative images of times gone by are among many contained in Haworth Timelines, a book by Yorkshire-based local history author Paul Chrystal, that looks back at the village over time.

It focuses upon the period when the community’s most famous residents, the Brontes, lived there. They arrived in April 1820, when Patrick, their father took up the post of curate.

‘When Patrick Bronte arrived he inherited a parish blighted by unemployment,’ writes Chrystal, adding that Haworth men typically had two jobs to make ends meet.

He goes on to describe the harsh living eked out either in agriculture or textiles. ‘Food was relatively scarce, often little more than gruel or porridge, resulting in widespread vitamin deficiency. As noted, public hygiene was atrocious: lavatories were crude. The facilities at the parsonage were no more than a plank across a hole in a hut at the rear, with a lower plank for the children.’

Dental health was poor. Charlotte Bronte in her thirties was described by Elizabeth Gaskell as having a ‘toothless jaw’, a ‘large mouth and many teeth gone’.

The paperback includes Haworth before the Brontes, with sections on the Parsonage and the village’s chapels and schools.

Chrystal refers to Charlotte Bronte’s complaint as to the ‘apparent ignorance of the Haworth people’, yet adds that ‘this is hard to reconcile with the strides various church officials, not least her own father, made in advancing educational opportunities in the village.’

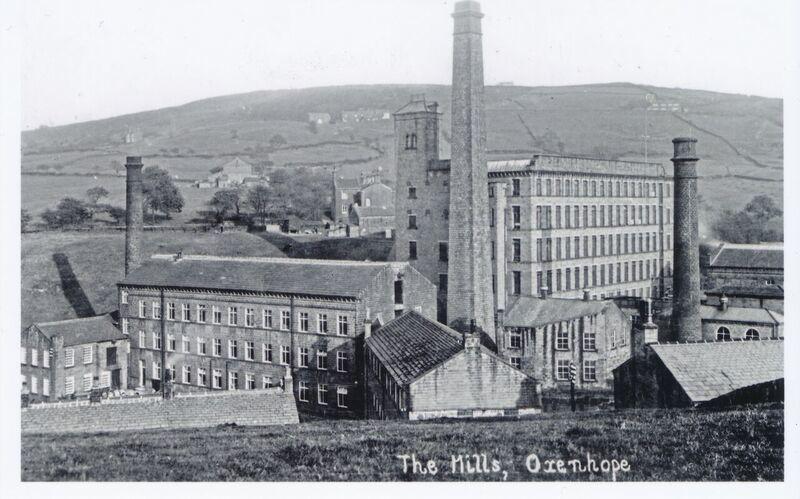

The wild, moorlands associated with the Bronte novels were how many people saw Haworth, but there was another side to it. Chrystal refers to author John Bowen’s work ‘Walking the landscape of Wuthering Heights’, in which he says ‘it is important to remember that Haworth was a modern working town with several mills and a good deal of industrial unrest. ‘

In the 19th century child labour was common in Haworth’s textile mills. In 1833 half of the 60 hands at Bridgehouse mills - Haworth’s biggest factory - were under 16; some were under ten. Before the Factory Act of 1833 hands worked 69 hours per week, 12 hours a day, nine on a Saturday. The eight full and three half-day holidays were unpaid.

One boss, Richard Butterfield, employed 42 under 16s and only four adults. He was, writes Chrystal ‘a tyrant and a bully whose style of management caused a stir at his mill’ The harsh treatment of staff went to a tribunal of sorts, which found in favour of the workers.

In the 1833 Factory Act no children were to work in factories under the age of nine (though by this stage numbers were few). A maximum working week of 48 hours was set for those aged nine to 13, limited to eight hours a day; and for children between 13 and 18 it was limited to 12 hours daily.

Only two of the Bronte sisters’ seven novels - Charlotte’s The Professor (1846) and ‘Shirley (1849) - deal directly or in any deal with factory workers and the textile industry that kept Haworth and its inhabitants alive. But while the latter treats the working poor sympathetically, ‘it is told from the point of view of the comfortably off factory owner and his family.’

Not everything relating to work was bleak. There’s a wonderful photo of a charabanc full of women workers from the firm Merrall & Son, dressed up in their best clothes and wearing summer bonnets, setting off for a day trip.

The book examines the village’s chapels and schools. ‘Along with the Brontes ‘Anglican church, the chapels often provided the village with education,’ writes Chrystal.

In 1851 Patrick Bronte’s average congregation was around 500 worshippers - very respectable given the population - but, between them, the three chapels drew in three times that.

Chrystal devotes a section to the Parsonage and the Bronte Society, which over the years has presided over a number of refurbishments, the latest of which was completed in 2013. The house was ‘faithfully redecorated’ using contemporary descriptions, surviving invoices and accounts, plus other evidence, to achieve its 1850s look. Most of the furniture is authentic, collected by the Bronte Society from the 1890s.

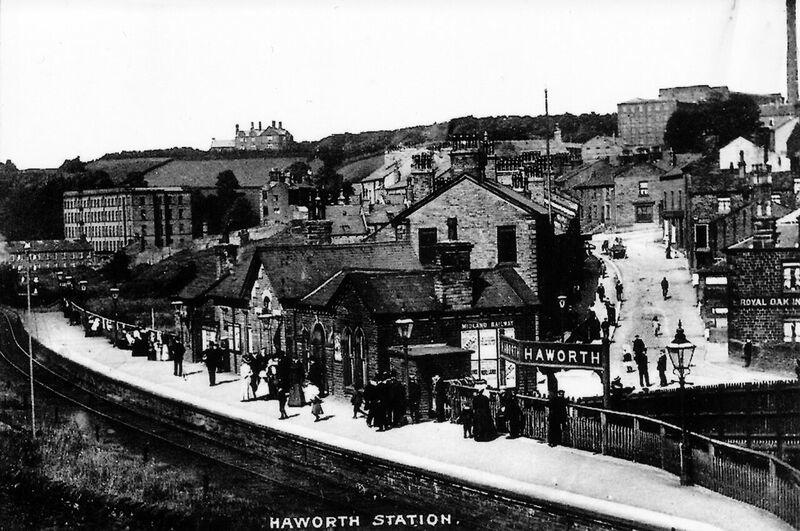

The Keighley and Worth Valley Railway features in the book. Previously a five-mile long branch line serving mills and villages in the valley. Building it, at a cost of around £36,000 (more than £3million today) was scheduled to take a year, but delays caused by buying the land, a cow eating the plans near Oakworth and various engineering problems lead to it overrunning by nearly a year. It opened in 1867. Saved after Beeching by a preservation society made up of local people and rail enthusiast, it now attracts 100,000 tourists every year.

Haworth Timelines by Paul Chrystal published by DestinWorld priced £12.99.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel