WEAPONRY of the First World War caused wounds never seen before. As Bradford soldier Private Walter Ashworth was to discover, trench warfare carried a high risk of horrific facial injuries.

Aged 23, Walter was the first man to join the 18th West Yorkshire Regiment (2nd Bradford Pals). On the first day of the Somme Offensive, July 1, 1916, he suffered gunshot wounds to his mouth, back and leg, destroying much of his face. He laid in a water-filled crater for three days until someone noticed him moving. Referred to the Cambridge Military Hospital, Aldershot, he was treated at pioneering plastic surgeon Captain Harold Gillies’s new plastic unit. Walter, who later moved to Queen Mary’s Hospital, Sidcup, was one of the first soldiers to have plastic surgery by Dr Gillies, whose methods were adopted by surgeons worldwide.

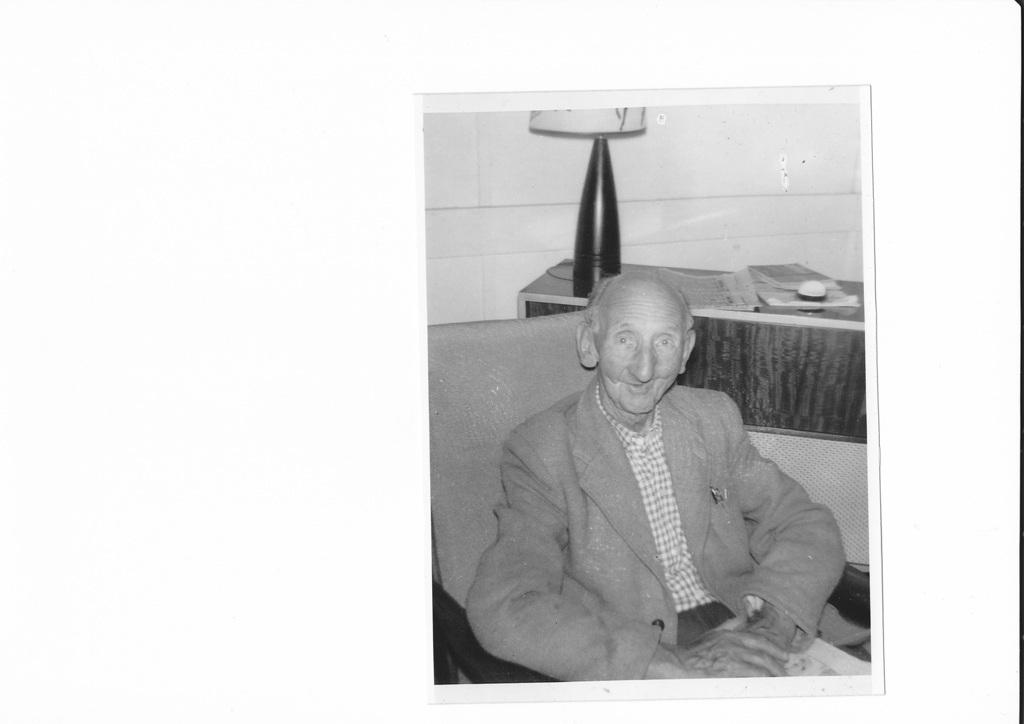

Walter suffered from his injuries throughout his life. “He recalled prejudice, because of his disfigurement, but never let it get him down,” says his granddaughter, Diane Smith. “He carried his facial scars and a shrapnel-riddled back all his life with dignity and bravery. We’re very proud of him. I still remember the humour in his eyes.”

Walter is remembered this week in an exhibition by Bradford World War 1 Group, exploring aspects of the 1914-18 conflict. “Only a few accounts survive of patients in First World War plastic wards,” says WW1 Group president Tricia Restorick. “Returning to civilian life, prospects for men like Walter with life-changing injuries were harsh. An estimated 300 disabled servicemen with families were looking for work in Bradford in 1919, employers were asked to contribute at least one opportunity for a disabled man.”

After his recuperation, Walter returned to the Bradford tailor’s shop where he’d served his apprenticeship but, with a severe facial injury, his boss made him work in a back room. “He was told he’d scare the customers away,” says Diane. “He was so upset he resigned, but a week later his boss begged him to return; the customers were outraged at his treatment and wouldn’t deal with anyone else. Bradford employers said all the Pals would have a job when they came back, but my grandfather felt too bitter to return to that employer.”

Walter married his fiancee Louise Grime while in hospital in 1917 and later built a new life overseas. “Before being shipped to France, he’d been sent to Egypt to defend the Suez Canal and met some Aussie diggers,” says Diane. “In 1922 - when Walter was still having operations on his face - Sir Harold Gillies suggested he go somewhere with a warm climate to build up his strength. He found jobs for himself and my grandmother out in the Australian Bush; a two-year contract as housekeepers on a huge sheep station. It was an adventure and people treated them with respect, as his face was so badly disfigured. Walter grew stronger and when the contract ended he vowed to come back and live here.”

Returning to the UK, Walter and Louise settled in Blackpool and opened a tailor’s shop. “When the Second World War began he tried to sign up - against my grandmother’s wishes!” says Diane. “They told him: ‘Mr Ashworth, you’ve done your duty. It’s the turn of these young fellows.’ He joined the Civil Service instead.

“In 1949 he and Louise came out to Sydney again, this time with me in tow, a full house of furniture and two dogs! We were later joined by my mother, stepfather and sister. We all went back to Blighty two years later, joining thousands of UK citizens known as the ‘Whinging Poms,’ as we all missed home. Then, in 1967, my grandmother died and Walter yearned again for Australia, so back we came! He carried Yorkshire with him wherever he went, with that strong Yorks accent of his.”

Walter was reunited with Sir Harold Gillies in the 1960s when the New Zealand-born surgeon tracked him down in Sydney and offered him another operation. “He said he could do a much better job second time around,” says Diane. “My grandfather thanked him but said he couldn’t go through another operation. I think he’d suffered too much, even though medicine had moved on a lot.”

Walter’s injuries took their toll on his work in later life. “He still carried bullets in his back which had moved and were pressing against nerves, giving him a lot of pain, so he applied for a British pension,” says Diane. “He was refused, which hurt him badly. After re-applying, a doctor examined him and in due course he received a pension. He started to have problems digesting food due to his facial injuries, and in 1977 he died of pneumonia.”

Bradford’s Shared Remembrance exhibition looks at those who, like Walter, returned from the war. The WW1 group has a database of survivors and is helping visitors piece together their family stories.

The exhibition was opened by Lord Mayor of Bradford Councillor Zafar Ali, who spoke about his relatives serving in the British Army in both World Wars. “He underlined the message that almost everyone in Bradford today will have a connection with the Great War. We should cherish this common bond,” says Tricia.

* Shared Remembrance is at Bradford Mechanics Institute Library, Kirkgate, Bradford, until Sunday. Call (01274) 722857 or visit ww1bradford.org

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here