ON September 24, 1937 the Telegraph & Argus reported on a team of hardworking volunteers turning a sanatorium near Keighley into a home for more than 100 children fleeing wartorn Spain.

They were among 4,000 children evacuated to the UK during the Spanish Civil War following the destruction of Guernica and other towns in the Basque region by General Franco’s fascist army, which eventually overthrew the Spanish Republican government in 1939.

Child refugees who came to Britain on the SS Habana in May, 1937 were from Bilbao. The boat docked in Southampton, where the children stayed before being moved across the country. Some came to Morton Banks Sanatorium in Riddlesden and a Dr Barnardo children’s home on Manningham Lane, which housed youngsters aged five to 15.

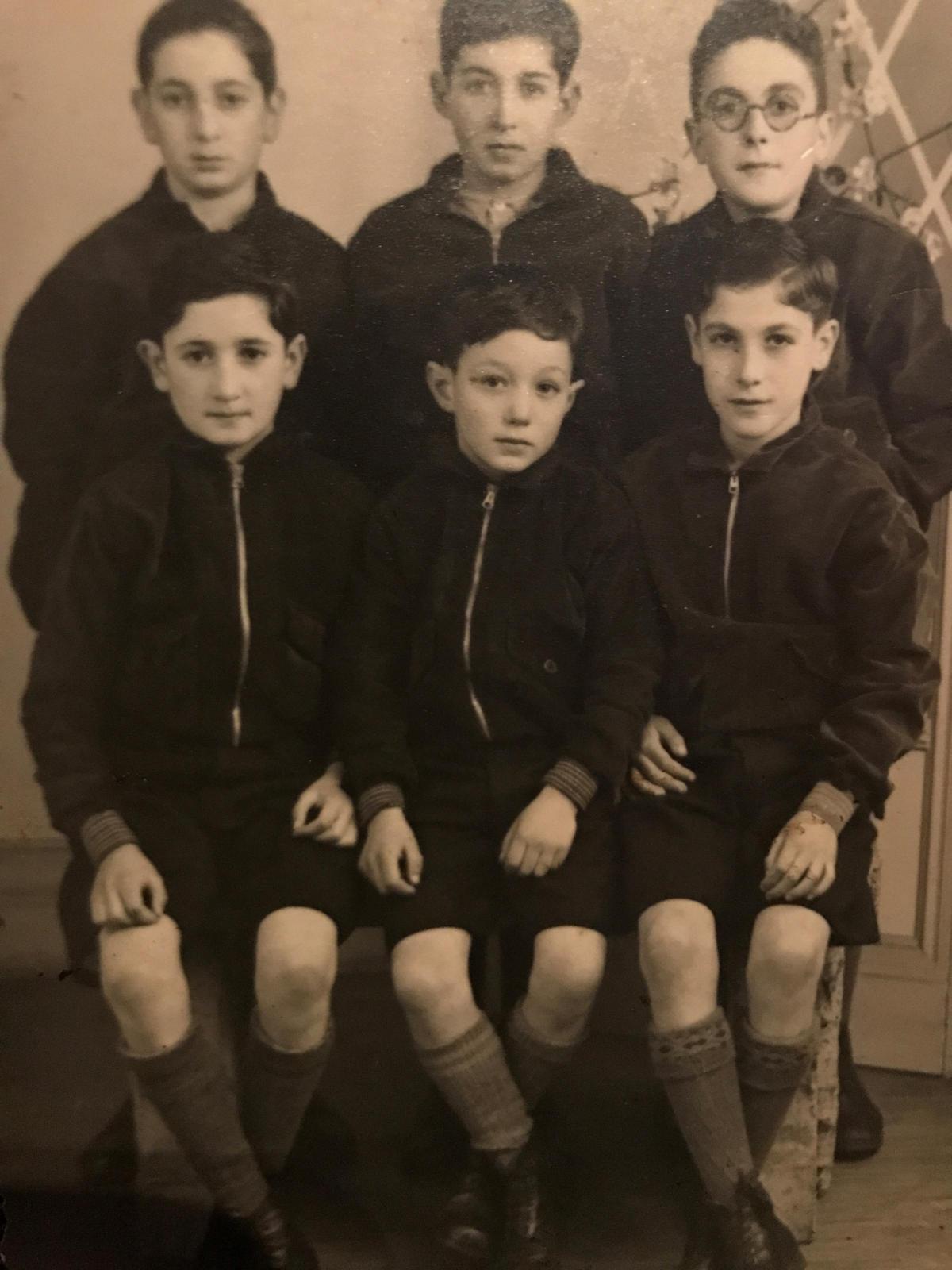

Roberto Garcia’s parents were both Basque refugee children. Arriving on the SS Habana, his father, Fausto Garcia, and uncle, Teodoro, were ‘adopted’ by a guardian who funded their stay in Britain. Fausto went to hostels around the UK, including Swansea and Oxford, and Teo was at Bradford’s Manningham Lane centre. Rob’s mother, Rosalia Blasco, came over with her mother, one of several Spanish teachers accompanying the children, and they lived in Birmingham.

The camps were requisitioned when the Second World War began, and most children were returned to their families, but about 400 stayed in the UK. Rob’s parents both remained, and met as adults. His grandparents, who opposed Franco, came to Britain after the war, and he has grown up with a strong sense of his Spanish heritage. Now Rob, a mandolin player, and guitarist Paul McNamara tell the Basque children’s stories through song, in their folk band, Na-Mara. The duo are at Bradford’s Topic Folk Club tomorrow.

“We sing about the Spanish Civil War, among a range of other songs,” says Rob. “For some children it would have been an adventure, but for many it must have been traumatic to leave their families, amidst all the bombing and devastation, for a strange country. It was the first exodus of children; they thought they were only coming for three months. Some were as young as four and by the time they returned home they could no longer speak Spanish. They had interpretors when they were reunited with their families.

“My dad had reunions over the years, but he didn’t talk much about being a refugee. My maternal grandmother lived with us, I spoke Spanish at home and grew up knowing about our heritage. But whenever we went to Spain my parents weren’t treated as Spanish, and over here they weren’t regarded as English.”

At first the British government said no to the child refugees, claiming it would be interfering in Spanish affairs but, following protests, children were allowed in - without their parents. “It became a humanitarian issue. People around the UK raised money to help look after the children,” says Rob. “It was very divisive at the time though. It happened 80 years ago but there are parallels with what’s happening in Syria today, and the unaccompanied child migrants. It doesn’t go away.”

An exhibition on the Basque children at Bradford’s Peace Museum in 2016 included drawings by youngsters of their homes in Spain. Most were of bombs being dropped on houses, and burning ruins.

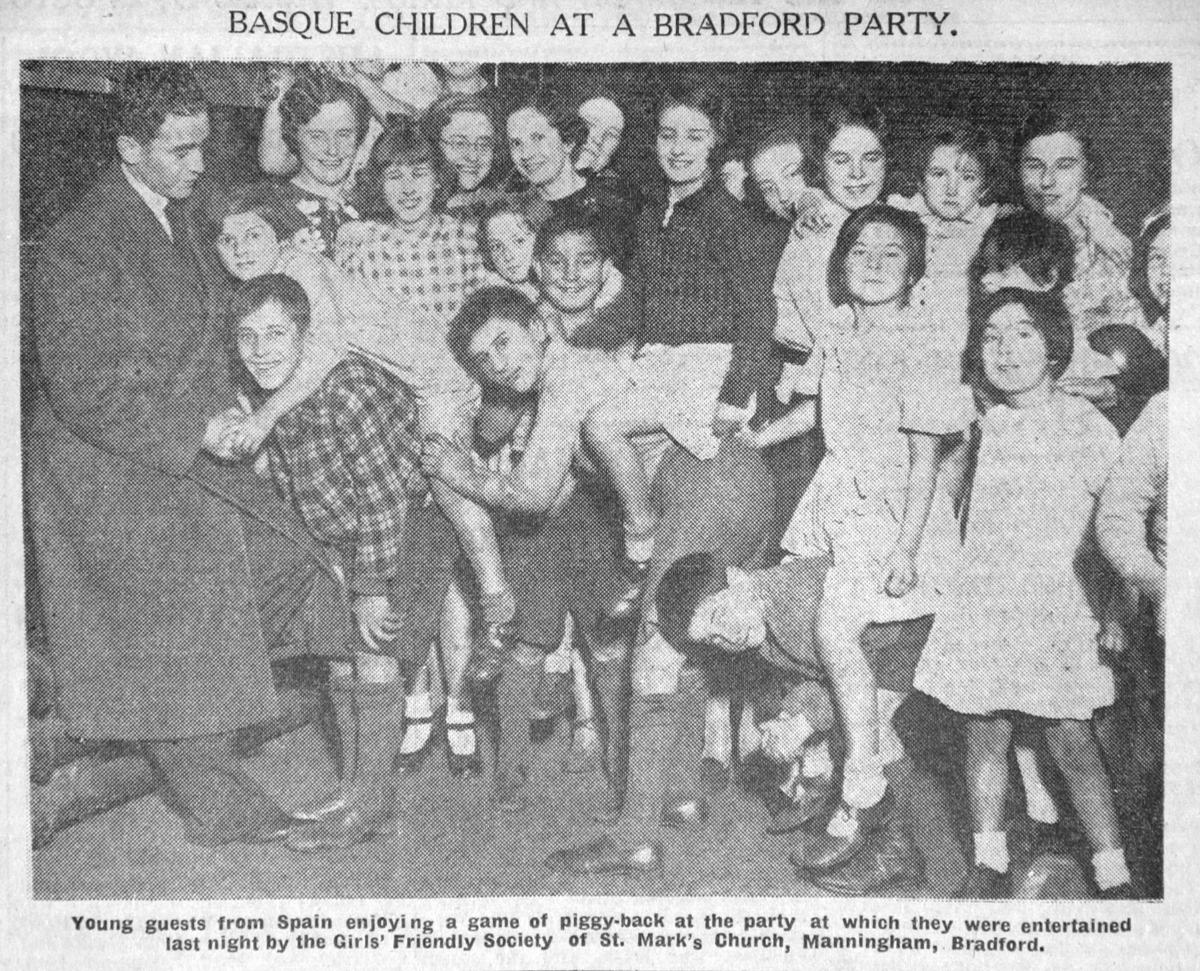

In Bradford and Keighley, the children found refuge; welcomed and cared for by local people and organisations. The Morton Banks hostel was the largest in Yorkshire, hosting 120 children and seven teachers and auxiliaries (“maestras” and “senoritas”), and 24 children were in Bradford. Each home had a matron and was run by volunteers. Children were ‘adopted’ by people who gave ten shillings a week for their upkeep and treats on birthdays. Others provided services such as dentistry, boxing lessons and interpreting. In an article on the Morton Banks home, the Telegraph & Argus, which also ‘adopted’ some children, reported that “Senor CV Alonso, an English-speaking Spaniard who came with the children said the idea is to organise the camp on a communal basis. It is hoped to complete arrangements for lessons in the concert room, and for recreation”.

Despite the language barrier, the children settled in at local schools. Football matches were organised, with shirts in Barakaldo team colours, there were Basque folk song and dance sessions and trips to the Alhambra and cinemas. Some children went skating on frozen ponds in January, 1938. One child described Keighley as: “Not pretty, not ugly, without a coastline but with swimming pools, a big park, three cinemas - The Picture House, The Regent, and The Cosy Corner - and a lake which froze over.”

* Na-Mara perform across Europe, delivering new, provocative songs in a traditional style about contemporary and historical topics. Their repertoire includes translations of Breton, French and Quebecois songs and their take on traditional music from Brittany and Spanish Celtic regions of Asturias and Galicia.

Na-Mara are at Topic Folk Club, Glydegate, tomorrow, 8pm. Call (01274) 271114.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel