He was the lifeguard who swam the Channel - a fitness fanatic, master horseman and exemplary soldier who died in a mental institution, misunderstood by his family. Newly found family mementos offer a more sympathetic understanding of the story of Sgt Stanley White whose nerves were shattered by years as a prisoner of the Japanese, as Tony Earnshaw discovers.

STANLEY White sat quietly on a bench and gazed out at the world. He said little, smiled occasionally and looked on with a mixture of bemusement and detachment at the children playing noisily around him.

It was the mid ‘60s and this strangely isolated man was receiving a rare visit from his Yorkshire relatives. Grace, his niece, had travelled from Brighouse to her home town of Dover to catch up with the White clan and to introduce her new baby son to his grandmother.

Also on the agenda was a catch-up with Uncle Stan. A photograph taken on the day shows a happy and smiling mother and children. The older man appears distant.

That is how Grace, now 76 and living in Scholes, remembers her uncle. Remote and uncommunicative. Spending time with him was something that had to be done. A duty, mainly to her grandmother, also named Grace. A courtesy borne of familial loyalties.

Husband Robin remembers him very differently: “We used to go and see him at the hospital where he was a patient and to get to him we had to go through several different wards. Every one of them was locked. Stan would come out and have a sandwich and a cup of tea in the grounds but there was always a warder there, watching.

“On one occasion at Grace’s mum’s house it was a Sunday and Stan came for tea. They let him out every so often. We were all sitting there and a Japanese war film came on the TV. And he flipped.

“He was underneath the table, coming out with bad language, trying to kill them. I was shocked. That was the first time I’d met him, and I was frightened. It shook me. They never let him out again after that.”

Adds Grace: “It was a shame, really, because he was a lovely chap.”

Stan has recently re-entered the Barracloughs’ lives thanks to the discovery at their home of a cardboard box filled with the everyday ephemera and detritus of family life. It yielded evidence of the extraordinary and tragic experiences of Stanley Ernest Paine White, a perfect British soldier whose nerves were shattered by war.

Now Grace is seeking to piece together the true story of the uncle whose mental breakdown made him a family shame.

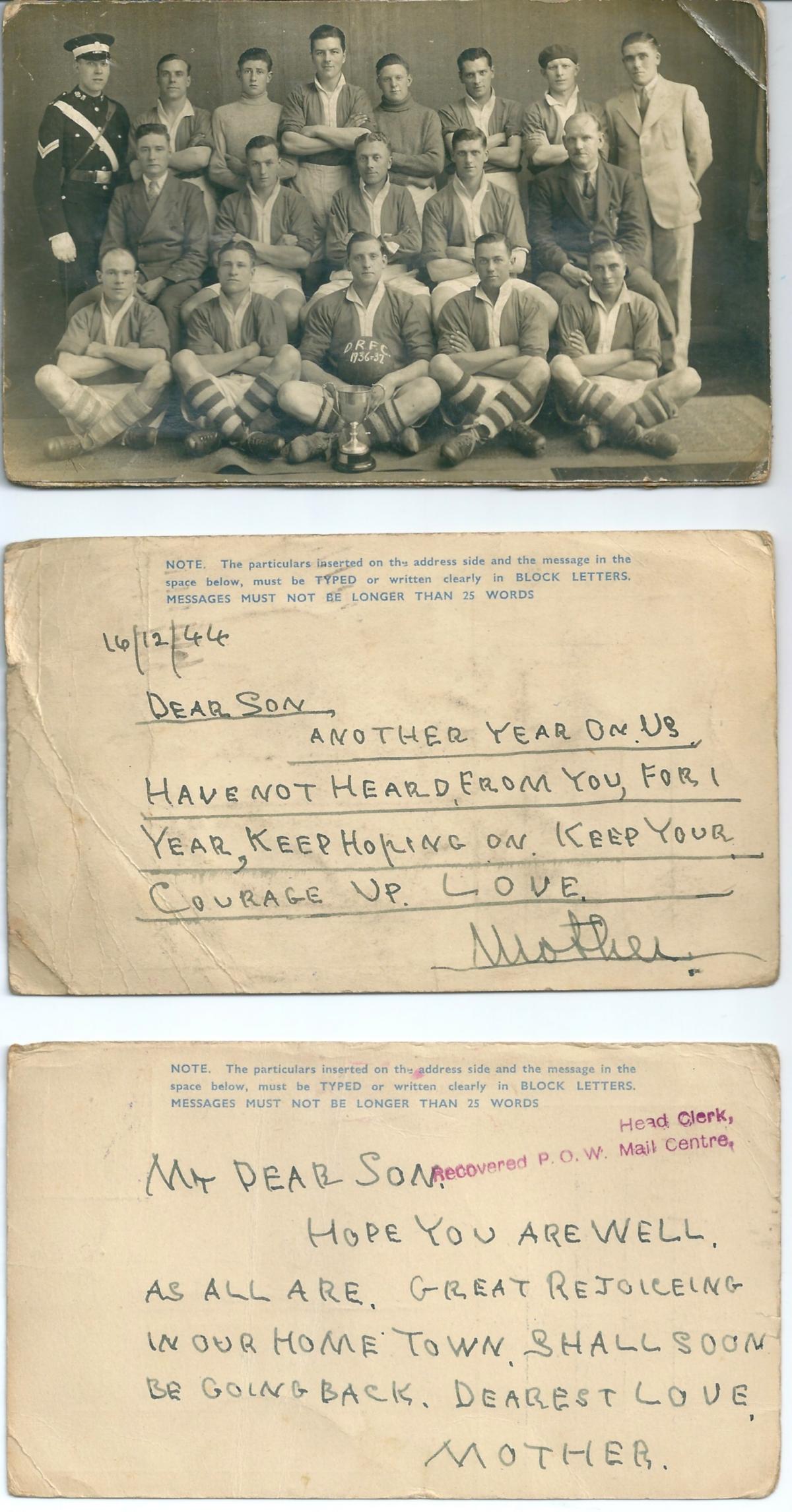

A family photograph, with Stan on the left

Born in Dover on March 1, 1907 Stan White was the son of Ernest, who died four days before Christmas, 1939, and Grace White. He was the eldest of their five children and grew up loving sport and horses. As a teenager he became a lifeguard and even swam the English Channel. An extremely fit, athletic and well-educated young man, he gravitated towards the army and enlisted three days after his 17th birthday.

Stan began what would become 22 years’ military service on March 4, 1924, when he joined the Territorial Army to become Sapper 2210562. In September the following year he transferred to the Royal Signals, the regiment with which he would remain as soldier and, eventually, prisoner of war.

Documents in the box outline Stan’s service. After an eight-year block with the Royal Signals he was called up on September 2, 1939. There followed 18 months in the UK before he was sent to Malaya, his first posting abroad.

Stan wrote several times to his mother from Malaya. Her responses have not survived but his letters are scattered with references to home and to life in a quiet zone of the war. “I’m okay myself and don’t mind soldiering here provided we are not messed about,” he writes in one. He mentions playing football – “a game here and there does one a world of good” – and how the heat and the “mossies” combine to be a nuisance. But there is entertainment in the form of movies, such as Boom Town, starring Spencer Tracy, and swimming.

“I wonder how Dover is looking just now with all the trouble at home,” he writes. “It does not stop the spring in its season and I can just imagine how nice the glades and woods must look with spring flowers such as bluebells and primroses, which are so plentiful around Kent.

“With so much rain this country looks very nice in parts. Bananas are very plentiful, also pineapples and coconuts. One can buy a bunch of bananas for the sum of 3d. Life here is very quiet but one can never tell with the war developing as it does. You can rest assured I am okay. I dreamt I saw Dad the other day. That is the second time since I’ve left England. I guess he must be around somewhere in spirit.”

A telegram from Stan's mother

Stan was captured on February 15, 1942 and sent to a Prisoner of War camp in Thailand, spending three years and 238 days in captivity.

“A group of them were captured in Burma, I think,” says Grace. “Later they all helped to build the Death Railway. In the camp he was the only sergeant in his section and must have been in charge. Or maybe he took charge. But he made a map of the camp and also drew up instructions for the other men as to how to write letters home.”

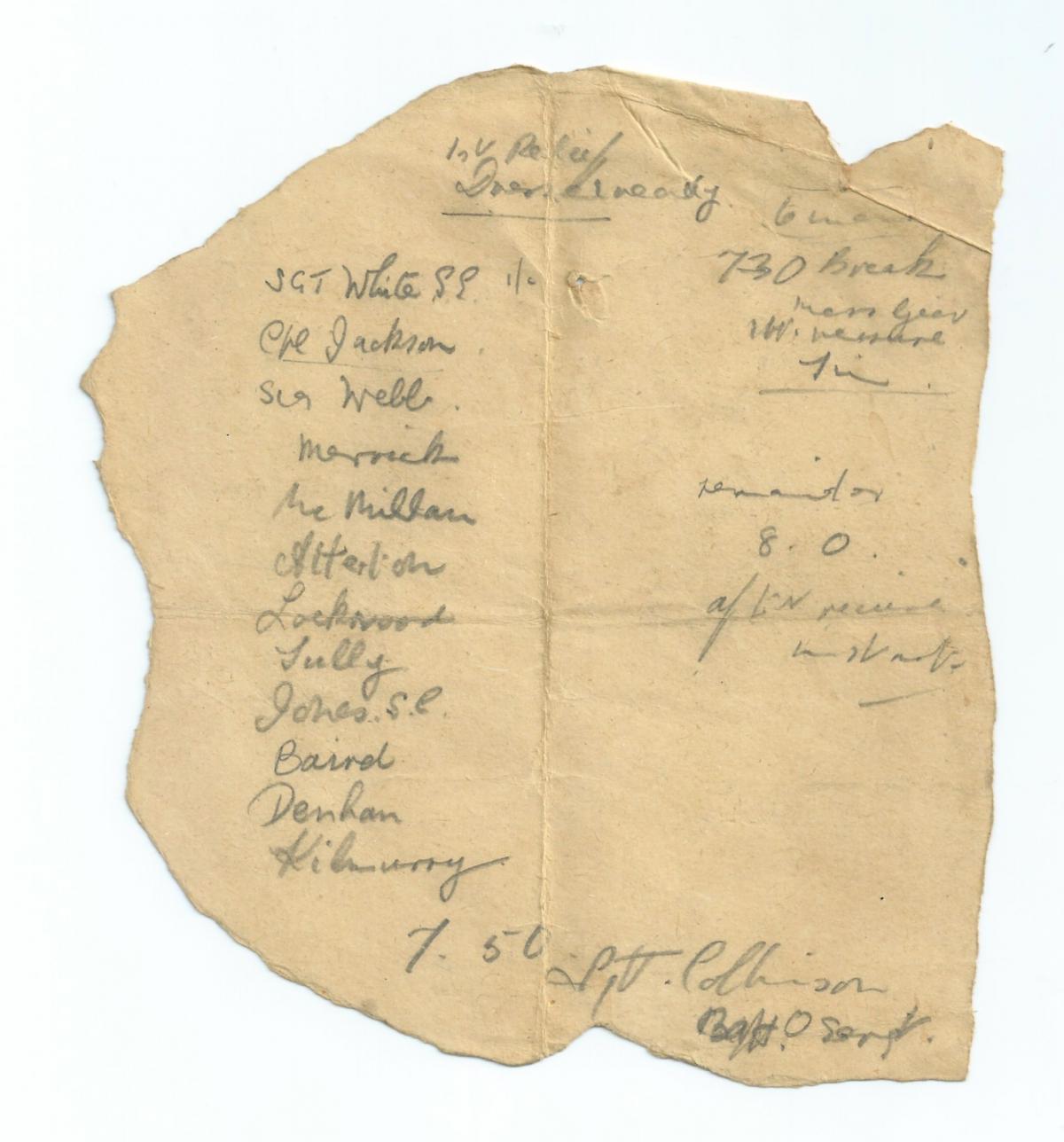

The personnel list and the letter-writing guidelines, written on thin cardboard from Red Cross parcels, have survived. They are much faded but point to a man attempting to maintain discipline and order in the face of extreme circumstances.

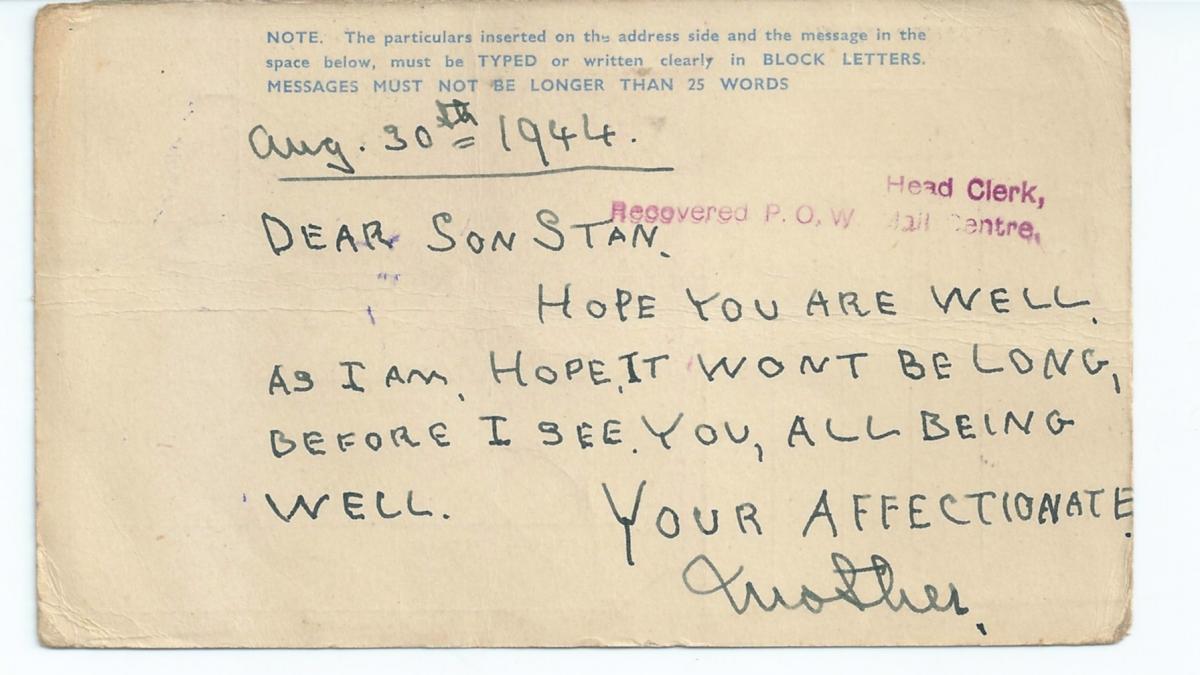

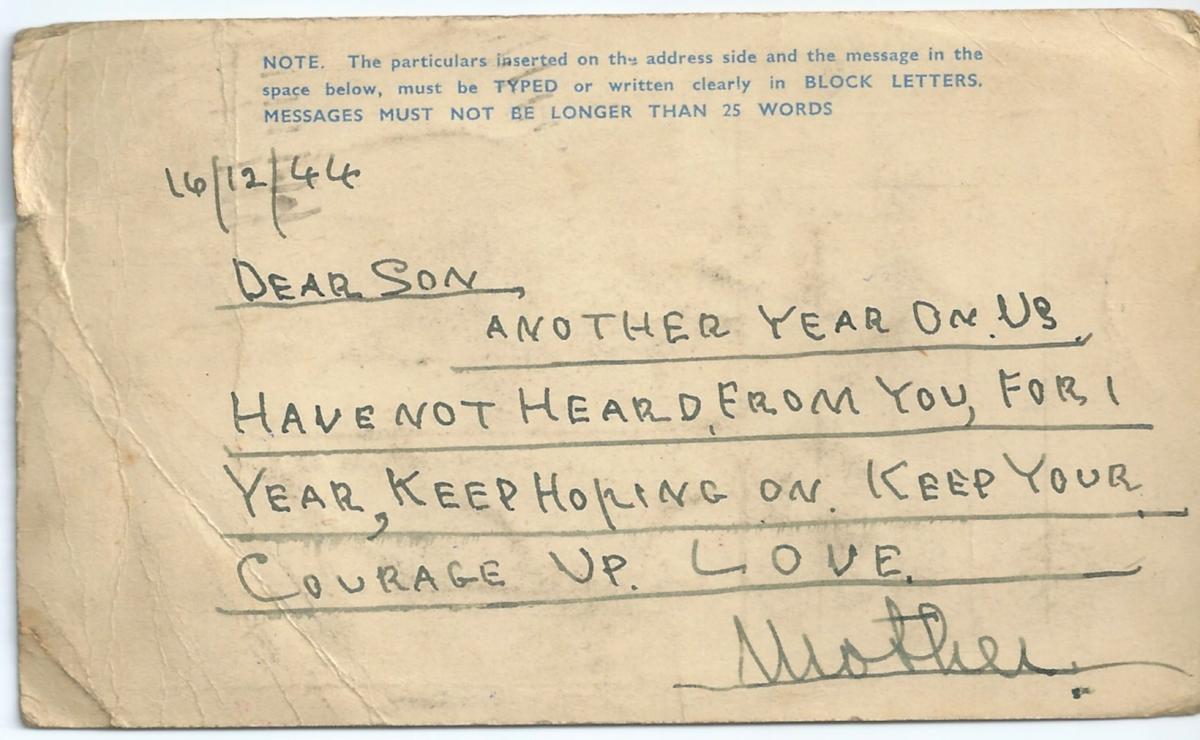

A series of postcards to Stan from his mother chart the increasing mood of disquiet that accompanies his situation as a PoW. One, dated December 16, 1944, reads: “Dear Son, Another year on. Have not heard from you for one year. Keep holding on. Keep your courage up. Love, Mother.” It was sent to Stan via Prisoner of War Post to a camp in Thailand. It came back to Dover almost a year later stamped “Returned as undelivered mails from territory formerly occupied by Japanese forces.” There were several others.

On being released Stan was repatriated to Britain retaining his NCO status. He was assessed in October 1945 and found to be suffering from a range of ailments including malaria. He was transferred to the army reserve on June 7, 1946.

But on November 14, 1947 his military career came to a halt. The stamp on his Certificate of Discharge reads: “Ceasing to fulfil Army Physical Requirements”. A final assessment of his conduct and character described him as “exemplary”. It added: “A steady, reliable and diligent man with a keen sense of responsibility. He is punctual and sober in his habits and is thoroughly honest and trustworthy. He is a keen and loyal worker and is capable of controlling and supervising others.”

Stan in his uniform

It had been more than two years since he had left the Far East. He was welcomed home to Noah’s Ark Road by his mother. But his behaviour was already providing cause for concern. Call it Shell Shock. Call it Battle Shock. These days it would be called by another name: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

So what happened to Stan “Blanco” White? And why, sometime in 1949, did he tip over into extreme mental instability? Grace takes up the story.

“I was born in 1939 and he came out of the war in 1945. I first met him then. I wasn’t that old but I do remember him. One night he set fire to the curtains in the house. So he had to be sectioned. He never came home. He was in St Augustine’s Hospital in Chartham. From then on he suffered with mental illness and never walked the streets again. He died in hospital.”

The clues to Stan’s experiences at the hands of the Japanese lay in the length of time he spent behind barbed wire, the deprivations he suffered, the illnesses listed on his Field Medical Card and his behaviour in the years that followed.

The punishment meted out to Allied PoWs by the Japanese is well documented. But many soldiers found it difficult or impossible to put their experiences into words. Stan never spoke in any meaningful way about his suffering. Instead its effects were manifested in extreme behaviour.

There are two key facets of PTSD. One is experiencing intrusive thoughts or images in the form of flashbacks. The other is avoidance – not wanting to discuss one’s experiences.

Dr Adrian Skinner, Clinical Psychologist and former Head of Clinical Psychology in Harrogate, says Stan’s behaviour was typically borne of experiences that could induce severe trauma.

“The country after the war was full of people that had suffered or were traumatised to a lesser or greater degree. The Japanese PoW camp was extra special. It introduced new levels of concentrated beastliness. PTSD was recognised even if it was not given that label. It was recognised as a mental disorder and it’s more likely than not that people did talk to him about it. Unfortunately it just wasn’t enough to recycle him into society.

“Diving under the table is par for the course. A lot of people exposed to military trauma fear being taken back to an experience that they find appalling. Seeing a film on TV is a frequent culprit. We can deduce that something very strange was going on in his head and that setting fire to the curtains seemed like a good idea.”

He says the stigma of mental illness was “still pretty rampant” in the 1950s. That allied to fear, anxiety and non-understanding of the condition meant society turned its back on many of those displaying acute psychiatric behaviour.

“At the time you would get large numbers of people that slid into the back wards of psychiatric hospitals where the treatment was custodial and caring rather than active. It was about monitoring. Stan became institutionalised.”

It offers a degree of comfort to Grace and Robin, and goes some way to explaining the family’s reaction over almost two decades.

“He had a 20-year period of struggle,” says Grace. “When he came back to England he was the never the same man. He came home poorly. He didn’t have a life. He was no good to anybody. It ruined his life, definitely. He never talked about it. He became an outcast. It was terribly sad.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here