FOR the British public, wars before 1914 were conflicts that occurred in far away lands, but as the First World War entered its second year, that image had already been challenged as war's reality was increasingly felt around the country.

In December of 1914 the towns of Hartlepool, Whitby and Scarborough had come under fire from German warships leaving many dead and injured. From the air came the threat of bombing raids as giant cigar-shaped Zeppelins flew over our towns and cities. On the seas around Britain a new weapon in the form of the submarine, or U-boat, appeared which quickly began taking a toll on allied shipping.

On February 4, 1915, Germany declared the seas around Britain a war zone. Two weeks' grace was given before allied shipping would become legitimate targets on February 18.

MORE NOSTALGIA HEADLINES

For the people of Britain, who relied upon food and raw materials arriving on the shipping lanes, this proved to be a near disaster as the war progressed.

In the first month alone, U-boats had sunk around 85,000 tons of allied shipping. This had an impact on passenger transport between North America and Britain, but there were still enough people willing to take the risk and cross the Atlantic on the lavish vessels of the Cunard Line.

On the afternoon of May 7, 1915 the liner RMS Lusitania was rounding the south coast of Ireland. She had made over 100 crossings between New York and Liverpool, and was almost home. Lying in wait was U-20 commanded by Kapitanleutnant Walther Schwieger and his last remaining torpedo.

The Lusitania still held the ‘Blue Ribbon’ for the fastest crossing of the Atlantic and ordinarily would easily out run any U-boat, but on this day the giant four-funnelled vessel sailed straight across U-20s path.

Schwieger fired his torpedo and within minutes of the ship been struck she began taking in water through the gapping hole in her side. There had been no evacuation drills during the voyage and many lifeboats failed to get launched.

At 2.28 pm, 20 minutes after the torpedo struck, the Lusitania vanished beneath the waves with the loss of 1,195 passengers and crew.

The loss of the ship caused outrage around the world. America lost 128 of its nationals, including millionaire sportsman Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, but it was still not enough to bring the world’s largest industrial nation into the war.

Nowhere, it seems, was unaffected by the incident and Bradford was no exception. Among those that perished was 21 year old Harry Long from Undercliffe.

Harry was born in Bath but had lived for many years with his parents in Cordingley Street off Otley Road. His elder brother, William, went to America to work in the Ford automobile factory in Detroit and Harry followed him over.

However, Harry’s twin brother Percy caught pneumonia and died within a week. Their mother sent a telegram and he replied saying he would catch the next ship back for England. He purchased a third class passenger ticket on the Lusitania, but never made it back to Bradford.

Another passenger, initially listed as missing was a seventeen year old youth named Allan Swallow, whose parents lived at 3, Albion Street, Buttershaw.

Allan was formerly employed at Lingards offices, Bradford, and left to pay a visit to his aunt at Hamilton, Canada, two years earlier. He had previously expressed his intention of coming home, but his parents had requested him to postpone it until it was safer, has he was their only son, and was a youth of considerable promise.

They had no idea he was on the Lusitania until the morning after the sinking, when they recieved a letter from him saying that he had decided to travel by the Lusitania in company with a young man from Sheffield.

In the letter he expressed confidence that they would be quite safe from submarines as the boat was well protected. Sadly Allan’s confidence in the ship’s ability to ward off U-boats cost him his life.

On the morning of May 7, 1915 Harry Taylor set off to Liverpool to meet his fiancee, Miss Ida Exley of Barry Plains, Massachusetts.

Harry, who was in the painting and decorating business with his father, Mr. Henry Taylor, at 425, Tong Street, Dudley Hill, had arranged for the marriage ceremony to be performed by special licence on Monday, May 10, 1915.

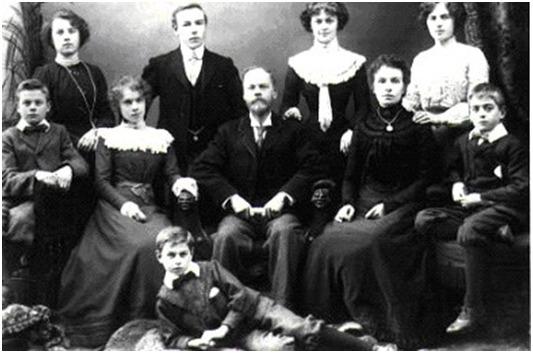

Ida, 21, was the daughter of Joseph and Hannah Exley who were originally from Shipley. Joseph, a wool sorter looking to escape the smog filled industrial streets, and his family had emigrated to New England in 1910. It proved to be a good move and five years later he had his own farm on Barry Plains, Massachusetts.

Instead of his bride-to-be waiting for him in Liverpool, all that met Harry was the terrible news that the Lusitania had been sunk and that Ida had not made it to safety. Harry would have to return home to Bradford and break the distressing news to his family and Ida’s relatives who still lived in Shipley.

Among all of this tragedy here was also those who had survived the atrocity such as a family from Great Horton. They were Mr and Mrs Eddie Riley and their young twin children.

For several years the Riley’s had been living in Lawrence, Massachusetts which is located 25 miles north of Boston, and was built in the 1840's as the USAs first planned industrial city.

The massive mill buildings lining the Merrimack River, produced both woollen and cotton textiles for the American and European markets and many families from the North of England emigrated there as both living standards and wages were much better than could be expected back in England.

For reasons unknown the Rileys boarded the Lusitania to return to Bradford and, having made several previous crossings of the Atlantic, were not too worried about the threat from enemy submarines as both passengers and crew did not believe the Germans capable of committing a felony against a civil passenger liner.

Thoughts of and attack seemed to fade as the ship began its home run and everyone was in high spirits prior to the torpedo finding its mark.

The Rileys were fortune to be placed in one of the first life boats which was launched successfully. Minutes later and they would have perished as the ship began to list preventing more boats from been launched.

Having witnessed the scenes of men, women and children screaming for help, and the whole sea strewn with human beings and floating wreckage, the family were naturally in a state of shock when they arrived at the house of Mr Timothy Taylor, the father of Mrs Riley, at 33, Ewart Street, Great Horton the following Monday.

After not sleeping for three nights, Mr Riley remarked that it felt grand to be back home again, surrounded by their friends and family.

A lucky escape was also made by Mr Henry G. Burgess, head of shipping department at Masrs. Wm Wade & Co, stuff merchants. He had not intended to sail on the Lusitania, but was driven to do so because the Anchor Line Cameronia, on which he had booked his return passage, had been taken over by the British Government.

Like most passengers he did not take the warning issued by the German Embassy seriously and was not duly worried about the possibility of attack.

Henry was in the dining saloon finishing lunch when the torpedo struck the ship’s hull. He immediately went up on deck, saw that things were pretty bad, and returned to his state-room to put on his life jacket.

Once back on deck he assisted in lowering the boats then went to the Marconi wireless operator to check if a message had got away. The operator told him it had and threw him a office chair by way of something to cling to if he was suddenly plunged over the side.

Two or three minutes later there was another tremendous list, which he thought was a second torpedo hitting the ship, and Henry realised the ship was going down.

At this point the ‘Marconi Operator’ came out of his office and began taking pictures on his camera! Weather he or his film survived is not know.

Henry Burgess jumped into the first boat he saw. There were a few others also in the boat and a steward was desperately trying to cut the ropes with a pen-knife. The ship heeled over causing Burgess and his fellow passengers to be thrown into the sea.

He managed to grab hold of some wreckage and drifted away from the sinking vessel. After about an hour in the water Henry was picked up and taken to Queenstown, Ireland.

After arriving back in Bradford on the morning of Sunday, May 8, 1915, Henry was met by Councillor William Wade and was able to recount the tale of his most fortunate escape.

The sinking of the Lusitania has been the subject of controversy for many decades. This was because the Germans believed she 'carried contraband of war' and 'was classed as an auxiliary cruiser,' which made her a legitimate target.

Cunard, unable to foot the full cost of building Lusitania and her sister ship Mauretania, had asked the British Government for help. This was granted on the understanding that the admiralty’s designers made ‘modifications’ should both vessels be needed for war duties.

The British denied any claim that Lusitania was carrying ammunition, but the fact was that the modified holds were packed with around 4,200,000 rounds of rifle cartridges, 1,250 empty shell cases, and 18 cases of non-explosive fuses. It also came to light that those ‘empty shell cases’ were in fact 1,248 boxes of filled 3" shells totalling 50 tonnes.

Kapitanleutnant Schwieger’s log noted an unusually large explosion followed by a black cloud after his torpedo struck. Then there was the second explosion, at first thought to be another torpedo striking the ship.

In 2014, a release of papers revealed that in 1982 the British government warned salvage divers that there was indeed a large amount of ammunition in the wreck, some of which remains in a highly dangerous state.

The date of May 7, 2015, marks the 100th anniversary of the sinking of Lusitania. To commemorate the occasion, Cunard's MS Queen Victoria is undertaking a voyage in May 2015 to Cork in commemoration of the loss of the big ship."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here