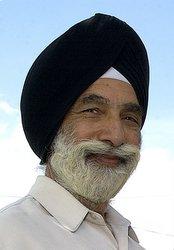

Dr Ramindar Singh is a former lecturer in economics and head of contemporary studies at Bradford College. He is the author of The Struggle for Racial Justice: from Community Relation to Community Cohesion; The Story of Bradford 1950-2002.

The regional master plan, representing a shared vision of 11 local authorities about their future prosperity, under the title Leeds City Region Development Programme, is a commendable long-term blueprint.

It acknowledges that local authority boundaries are irrelevant to those looking for rewarding job opportunities, and recognises the interdependence between developments in housing, education, transport and economic growth.

So far, Bradford's economic prosperity has largely come from spending lead growth'. The city has benefited from tourism, large government grants for economic regeneration and other projects and private sector investments in housing. Jobs and incomes generated through short-term public sector funds soon reach their peak. And consumer spending-led economic growth doesn't create a self-sustained economy. A stable self-sustained economy for the city is possible only through investment-led growth in areas such as electronics, and digital technology industries as proposed in the master plan.

However, turning the plan into reality would very much depend on future co-operation between the elected politicians and the location of new businesses or public sector projects. Any efforts to weaken local identities or local influence on decisions are destined to raise tensions and revive traditional local rivalries. The sharing of benefits from new investments and future prosperity also depends upon the Council's capability to exploit the new opportunities open to them.

The economic principle of comparative advantages for economic growth is relevant here. For instance, an expected rapid increase in the population of Bradford in the coming decades will mean labour in abundance. By exporting its labour beyond the city boundaries, it should be able to grab a large proportion of 150,000 new jobs to be created through an estimated £7 billion new investments in the region.

But, this is only possible if the new workers are more mobile and offer the skills appropriate to the specific needs of the labour market. Therefore, the quality and nature of education and training these youngsters achieve is going to be a decisive factor.

The biggest worry for Bradford should be the current dismal achievement of children in inner city schools. A big shift is essential in how young people view education and life in general. Schools and parents, working in partnership, can make a big difference in changing the culture of gloom and despondency from which many young people in inner city communities suffer. The long-term negative impact on life of welfare dependency culture' must be pointed out to them. To build their self-esteem and self-confidence, the prevailing race, religion or class-based notions of victimhood' among many young people must be challenged too.

The practice of frequently lowering targets set for achievement in schools for reasons such as English language deficiency in children on entering school, social deprivation, and parental attitudes must be challenged. Ways have to be found to overcome the negative impact of these long-term issues inhibiting improvement in standards.

If young people from Bradford fail to take up the new employment opportunities as envisaged in the plan, an influx of workers from abroad or from other parts of Britain would leave them in their current level of social deprivation. For the city, it might affect the current fragile community cohesion even more adversely.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article