The 90th anniversary of the Armistice of the First World War concentrates minds on the human cost of war.

Collective acts of remembrance also are a way of reminding ourselves that much as human beings have a shaping influence on their individual destiny, they have no control over fate, the unexpected event.

When 20-year-old Able Seaman Norman Walton found himself consigned to the burning, oily sea for the third time in the winter of 1941, he must have felt that intense burst of panic that comes with the shocking realisation that against the vast indifference of nature, one man’s hopes and dreams count for nothing – unless he survives.

In a short space of time the young man, who was a submarine-detecting Asdic operator, had had two small vessels sunk from under his feet by German dive-bombers.

“Twice within a few months in 1941 I was sunk, each time our ship being hit by those damned Stuka bombers which seemed to be everywhere in those days. Each time I was in the water for only a few hours before being picked up,” he later recollected.

During the evacuation of British and Commonwealth troops from Crete, his ship HMS Orion had been attacked with hundreds of casualties and fatalities. He had survived these experiences, as he had survived naval engagements in Norwegian waters between April and May, 1940.

And then on December 19, 1941, his ship, the cruiser HMS Neptune, got caught in an Italian minefield. The mines were laid at a depth of 70 fathoms. Just after midnight the first mine exploded. In all, four of them blew the ship apart. The order to abandon ship was given at about 2am. Other mines exploded under the cruiser Aurora and the destroyer Kandahar, eventually sinking the latter.

Three Royal Navy attack ships, based in Malta to disrupt convoys of tanks, fuel and supplies to Rommel’s Afrika Corps, had been removed from active operations. Hundreds of men were killed or wounded; but the most grievous loss of all belonged to the 6,700-ton HMS Neptune.

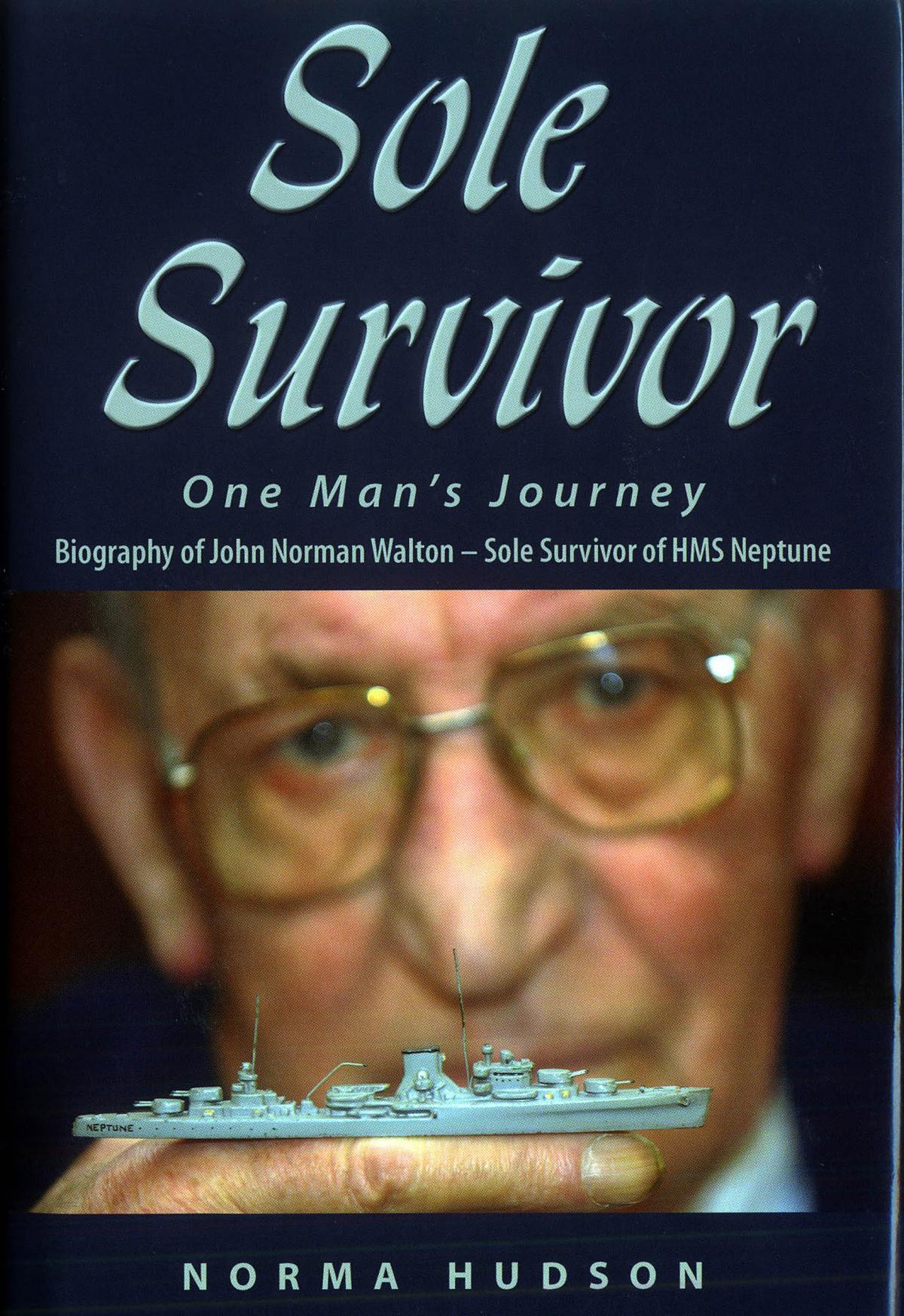

Using her Geordie-born father’s notes, discovered in a box after his death in his adopted home of Pudsey in 2005 at the age of 84, Norma Hudson pieced together the sequence of events.

“When Rory O’Conor (Neptune’s Captain) had given the order to abandon ship, everything happened so fast that almost anyone still below was trapped as water deluged madly through her open side. The telegraphists that were left would have died instantly as their second wireless transmitter office disintegrated when Neptune drifted sideways on to the last mine.

“So did everyone in the stokers’ mess-decks and low power room. Men in the torpedo room, keyboard flat and officers’ galley were hurtled into space by the eruption which also dashed men to their deaths against the bulkheads in the gunroom and marines’ mess-deck. There was no hope for those previously injured or for those caring for them in the sick bay. There was no hope for anyone.”

Just after 4am, Neptune was in her death roll. None of the four other ships in the attack force, Force K, were either too badly damaged to help or were not allowed to. The captain of the destroyer Lively asked permission to search for survivors. The reply came back: “Regret, not approved…I hate to leave them but I’m afraid we must.”

Thirty of the ravaged Neptune’s crew were in the water, in a Carley raft. Three miles away the crippled Kandahar, caught by strong winds, drifted further away. Some of the survivors lost the will to hold on and slipped below the cold, oily water. Kandahar, caught in the swell of high waves, took on more water and sank.

Able Seaman Walton had spent his first day hanging on to the raft and occasionally swimming around it to keep himself awake. His notes describe his struggle to survive.

“I get off the raft and swim round it a couple of times as I had been trying to do at regular intervals each day, but I find it too difficult, my leg joints and arm joints are not working. I can hardly see and think how much longer before somebody finds me. I’m still hoping for the best although there are only two of us left by the 24th (December). It’s getting a bit rougher and I’m thirsty. I can’t swallow as my tongue is swelling up.

“After five days in the water I was starting to wonder where were all the ships in the Med; British, German, Italian. I wasn’t bothered by this time as long as I get picked up. As I watched my shipmates die around me the guilt and depression was over-powering, not being able to help them and letting them go.”

The other man left in the raft was Leading Seaman Albert Price. But he died too.

On Christmas Day, 1941, battered and blinded by the effect of sea-water and oil in his eyes, Norman Walton awoke in an Italian hospital in Tripoli. All he could digest was a bowl of hot milk.

The circumstances surrounding the loss of all but one of Neptune’s 766 multi-national crew (more than 200 of whom were from New Zealand, South Africa, the Irish Republic and Australia) were kept secret. Next-of-kin merely received a telegram stating that their husband or son was “missing on active service”. There was no publicity.

Norman Walton’s will to survive stayed with him through the remainder of the war. He was a prisoner-of-war until 1943 when he was released. Back in England he married his sweetheart, Irene, and returned to active service. He was transferred to convoy duty on the terrible runs to Murmansk, and later went back to the Mediterranean.

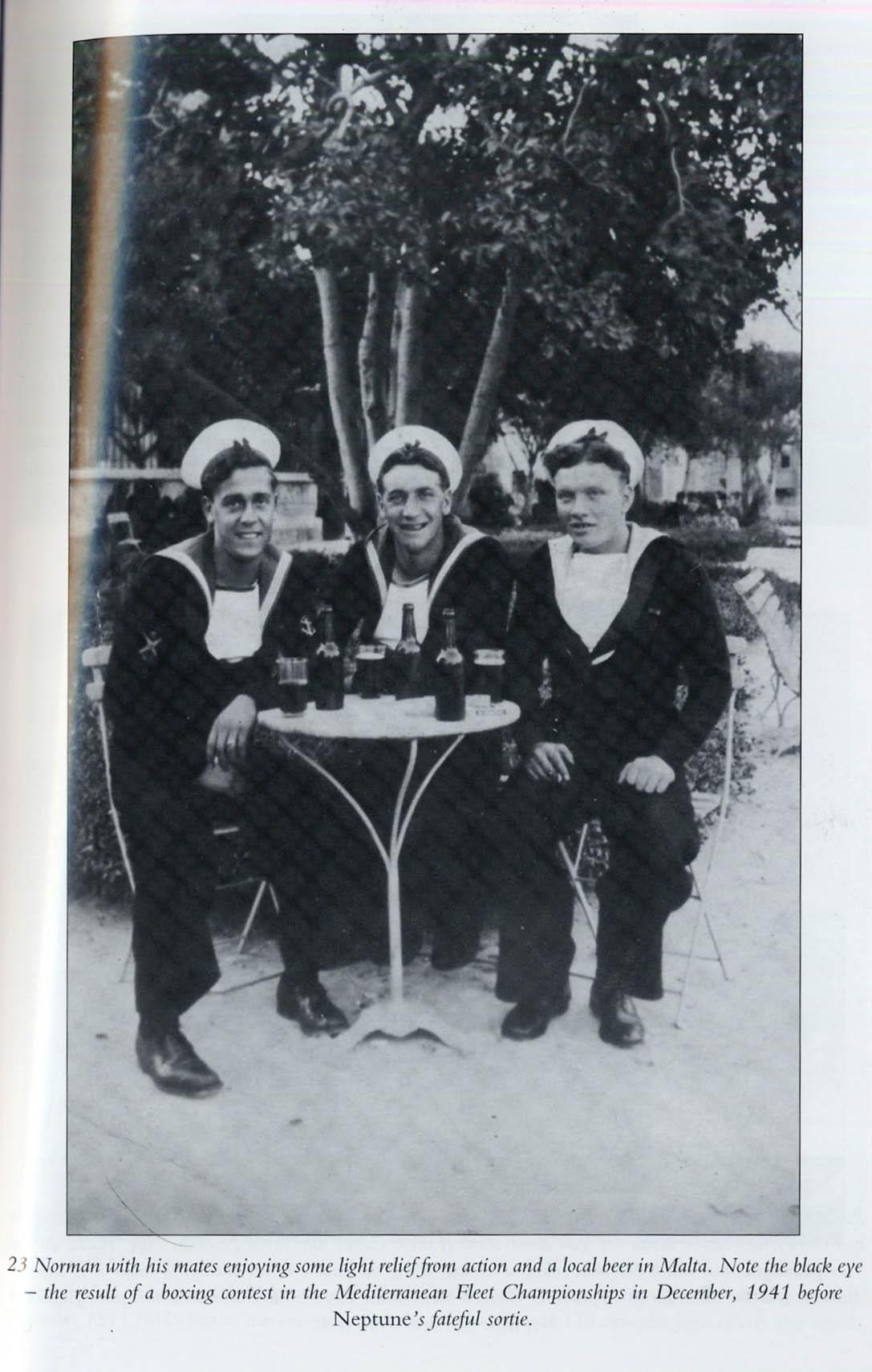

After the war he took up professional boxing as a middleweight in and around Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and fought 146 fights under the name of Patsy Dodds in fairgrounds and in the ring until 1952, when he rejoined the Royal Navy during the Korean War, finally retiring in 1957 at the age of 36.

Norman and Irene Walton had two children, but their son John died very young. Norma grew up and married. Her father and mother later moved to Pudsey. He worked for Glendinning (Containers) Ltd, in Armley Road, Leeds, rising to works manager and director.

Throughout his life he remained active in sport – a habit that he was wont to say helped to save his life in the cruel sea in 1941. He played bowls and darts and he and Irene were regulars in the Fox and Grapes public house, near their home on Smalewell Road.

Irene died in 2002, the year that the Neptune Association was founded, to honour the dead and survivors of Force K. Norman was invited to be its first president.

Sole Survivor – One Man’s Journey, compiled and written by Norma Hudson, is published by The Memoir Club at £19.95.

‘Diaries revealed so much’

Writer Norma Hudson, a 60-year-old grandmother-of-two, said of her father: “I did always know he was a sole survivor but he never talked about it, and I was so interested in getting on with my own life, I never asked him any questions.

“But when he passed away and I found his belongings, there was a wealth of diaries and writings and I felt I just had to document it all.

“There was too much history to throw away, but it was an emotional rollercoaster reading through it all because he was doing all this writing as a teenager, and was very young when it all happened.

Norma (pictured), a former teacher, added: “The research was very hard as I had to put it all into context.

“It has taken me nearly three years but I met some fantastic characters.

“I interviewed a lot of seamen who served in the Med and the Far East, and a lot of former boxers, and they were all great old blokes.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article