FLORENCE Farmborough was a governess when the First World War began in 1914. She spent most of the conflict on front lines, living among soldiers in field tents and dug-outs.

“At breakfast the news broke: ‘Russia is at war with Germany’. It seemed as though someone had drawn a curtain down on happiness,” Florence recalled. Soon after the outbreak of war, the British governess, who was working for a family in Moscow, volunteered for the Red Cross. She trained as a surgical nurse, passing her exams in Russian, and was assigned to a mobile unit of the Russian Army, close to fighting on the Eastern Front. An amateur photographer, Florence took her plate camera and tripod with her and captured striking images of daily life on front lines in Galicia, a region in present-day Poland and Ukraine.

Florence’s photographs, which include soldiers resting on haystacks and tending to their injured goat mascot, are part of a fascinating exhibition, No Man’s Land, of images taken by women in the First World War. In 1914, when war was declared, women weren't allowed to vote or fight in the armed forces. Yet many still wanted to be involved, and volunteered to help. Offering rarely-seen female perspectives - at Bradford’s Impressions Gallery ahead of a UK tour - the exhibition presents women at work as nurses, ambulance drivers and mechanics, as well as informal snapshots of soldiers and nurses at leisure, haunting images of execution sites, and innovative artwork inspired by war photography.

It presents women at work as nurses, ambulance drivers and mechanics, as well as informal snapshots of soldiers and nurses at leisure, haunting images of execution sites, and innovative artwork inspired by war photography.

No Man’s Land is accompanied by a £35,000 Heritage Lottery-funded project involving the gallery’s New Focus group of 16 to 25-year-olds. Visiting venues such as Bradford’s Peace Museum, they used wartime archives to create an impressive book about women’s role in the war, which is available at the exhibition and used in schools.

“Most people think of war photography as male soldiers in combat zones. With the First World War we think of soldiers in the trenches. Women’s role in the war didn’t make it into official history books,” says curator Dr Pippa Oldfield. “No Man’s Land shows how women have photographed war in many other ways, from different viewpoints.”

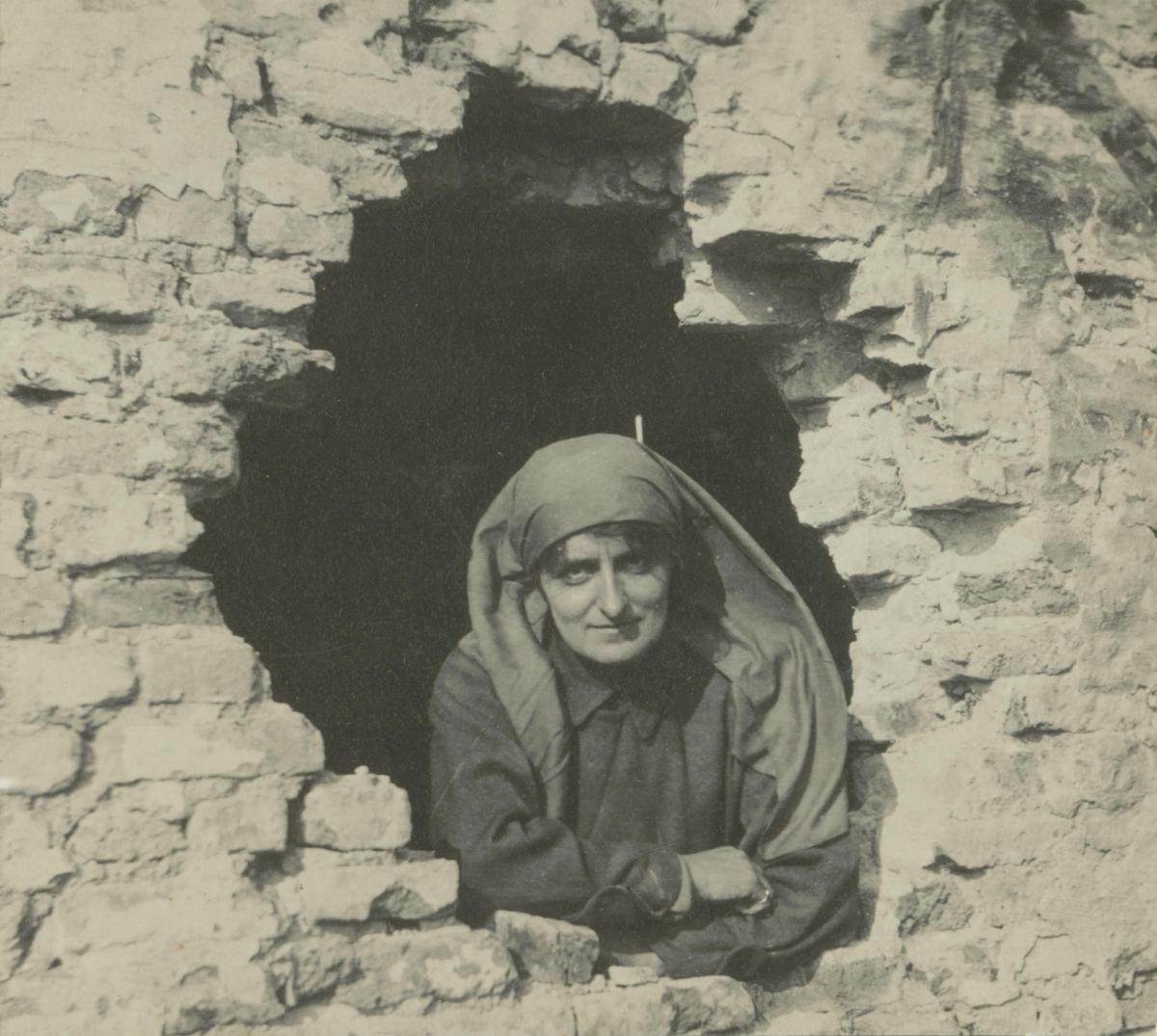

Mairi Chisholm was 18 when she ended up a long way from home in Scotland, at a medical unit in Belgium, as a volunteer with the Flying Ambulance Corps. There she met Elsie Knocker and, realising that many wounded soldiers were dying of shock between battlefield and hospital, the two friends turned the cellar of a bombed-out house in Pervyse, a Flanders village, into a First Aid post. While the British Army disapproved of their operation, Belgian soldiers appreciated the pair risking their own lives on the Front, calling them the ‘Angels of Pervyse. They returned to Britain in 1918, after surviving a poisonous gas attack, with medals for saving lives.

Mairi and Elsie used snapshot cameras to photograph life and suffering around them. “These cameras were quite affordable and made photography more accessible; the equivalent of using a Smartphone to take instant snaps like we do today,” says Pippa.

There is humour in some images; Elsie is snapped sticking out her tongue in a ‘selfie’ pose, two Belgian soldiers are on a makeshift see-saw, a ‘game of roulette’ against incoming bullets, and three others are larking around, balancing on each others’ shoulders. The women also captured the brutality of war, with Mairi commenting: “One sees the most hideous sights imaginable, men with their jaws blown off, arms and legs mutilated”. In one photograph, a dead German soldier lies in reeds by a river. British newspapers didn’t show corpses, but Mairi recorded several.

The exhibition also pays tribute to Olive Edis, Britain’s first official female war photographer. Olive was running her own business, photographing high profile figures such as David Lloyd George and Emmeline Pankhurst, when she was commissioned by the Imperial War Museum’s Women’s Work sub-committee to record the changing roles of women in war. On the battlefields of France and Flanders, she used a large plate camera from her Norfolk portrait studio, (often developing her pictures in x-ray units), to photograph women in traditional female roles such as nursing and driving ambulances, but also working in RAF engine repair shops. “These images were important in changing perceptions of women in work, against the backdrop of the women’s suffrage movement,” says Pippa.

Also featured in No Man’s Land are contemporary photographer Alison Baskerville’s portraits of female soldiers in Afghanistan. Using an early 20th century colour process, Alison was influenced by Olive Edis, who pioneered the technique in her Norfolk studio.

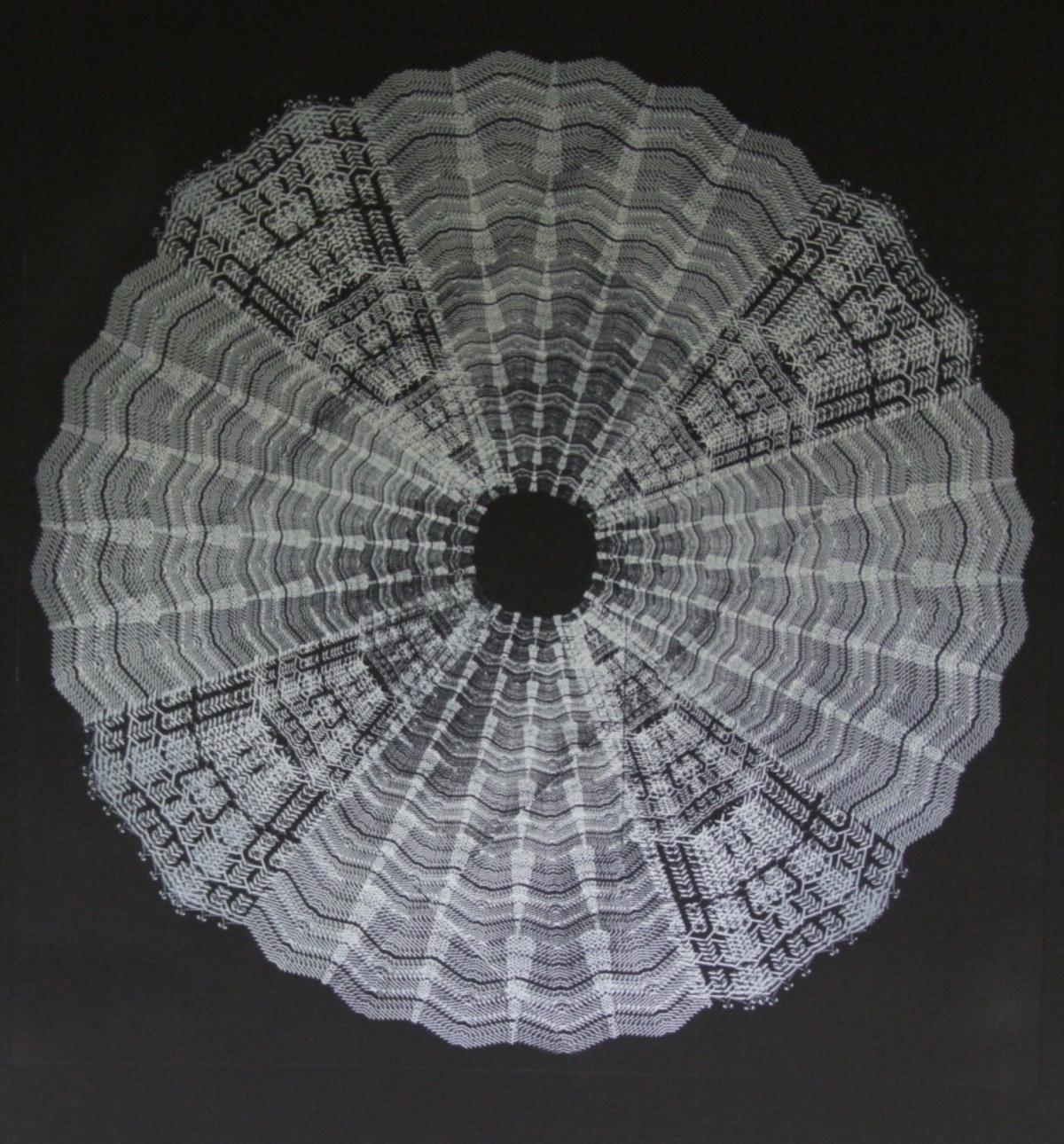

When artist Dawn Cole saved her great-aunt’s old suitcase from the skip, she discovered photos and diaries revealing a firsthand account of horrors of war. Clarice Spratling was a nurse in northern France from 1915-18. Struck by the contrast between her cheerful, composed photographs of nursing life, taken with a pocket Kodak, and her diary accounts of horrific soldiers’ injuries, Dawn created a series of remarkable lace designs. Combining photo-etching and digital manipulation, each bear words from Clarice’s diary - ‘Wound in back, bullets came out in front’, ‘Man had eyes removed’ - intricately woven through. “Lace has associations with the war; lace-making was a feminine pastime, and shellshocked soldiers made lace too. Lace-edged postcards were sent to loved ones,” says Pippa.

Around1,000 British, French and Belgian soldiers were executed by their own men during the 1914-18 conflict. Photographer Chloe Dewe Mathews visited execution sites to take a series of haunting images on the same date, at the same time, as some of the men were killed. Called Shot At Dawn, they include a brick wall strewn with bullet holes and present an eerie stillness, offering a different perspective from the archetypal action-packed war image. “As I stand in the 4am darkness at the edge of an empty field in Flanders, I know there is an absurdity to what I’m doing,” said Chloe. “But by photographing these places, I’m re-inserting the individual into that space, stamping their presence back onto the land, so their histories are not forgotten.”

* No Man’s Land runs at Impressions Gallery, City Park.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here