MARK Keighley spent his entire working life steeped in Bradford’s two major industries; wool textiles and engineering.

In 1962, after several years editing the company newspaper of Hepworth & Grandage, one of the city’s “Big Three” engineering firms, he joined the staff of the Wool Record, a magazine with a worldwide circulation covering the wool-textile industry.

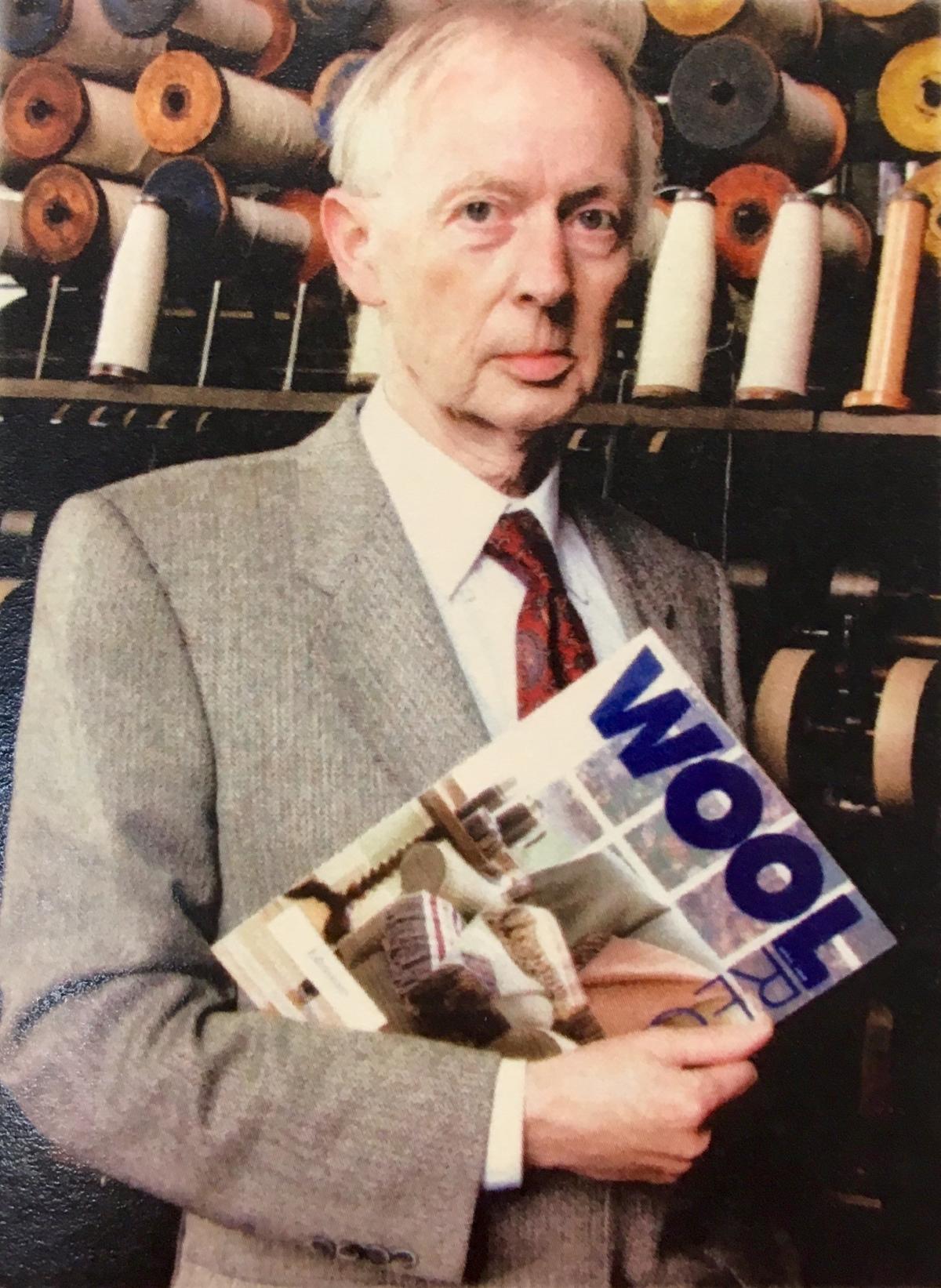

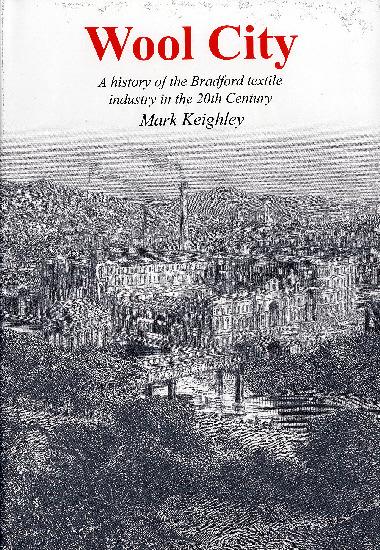

During the many years he wrote for and later edited the Wool Record, Mark became an authority on the industry. He drew on that vast knowledge for his book Wool City, a comprehensive account of Bradford and the industry on which its fortunes were founded. A decade later, in retirement, he realised there were still stories to be told and began writing a planned booklet to be entitled The Golden Afternoon Fading - a reference to the time in the 1960s when the decline of Bradford’s wool-textile industry had begun. His intention was to hand-print a few copies for friends and family.

“So much has happened in recent years that the 1960s and 70s now seem as remote as the 1920s,” he wrote. “After I had drafted the initial chapters I began to feel like the policemen who used to patrol the city’s streets after the pubs had closed - shining torches into shop doorways and dark corners, sometimes surprised by what they found.”

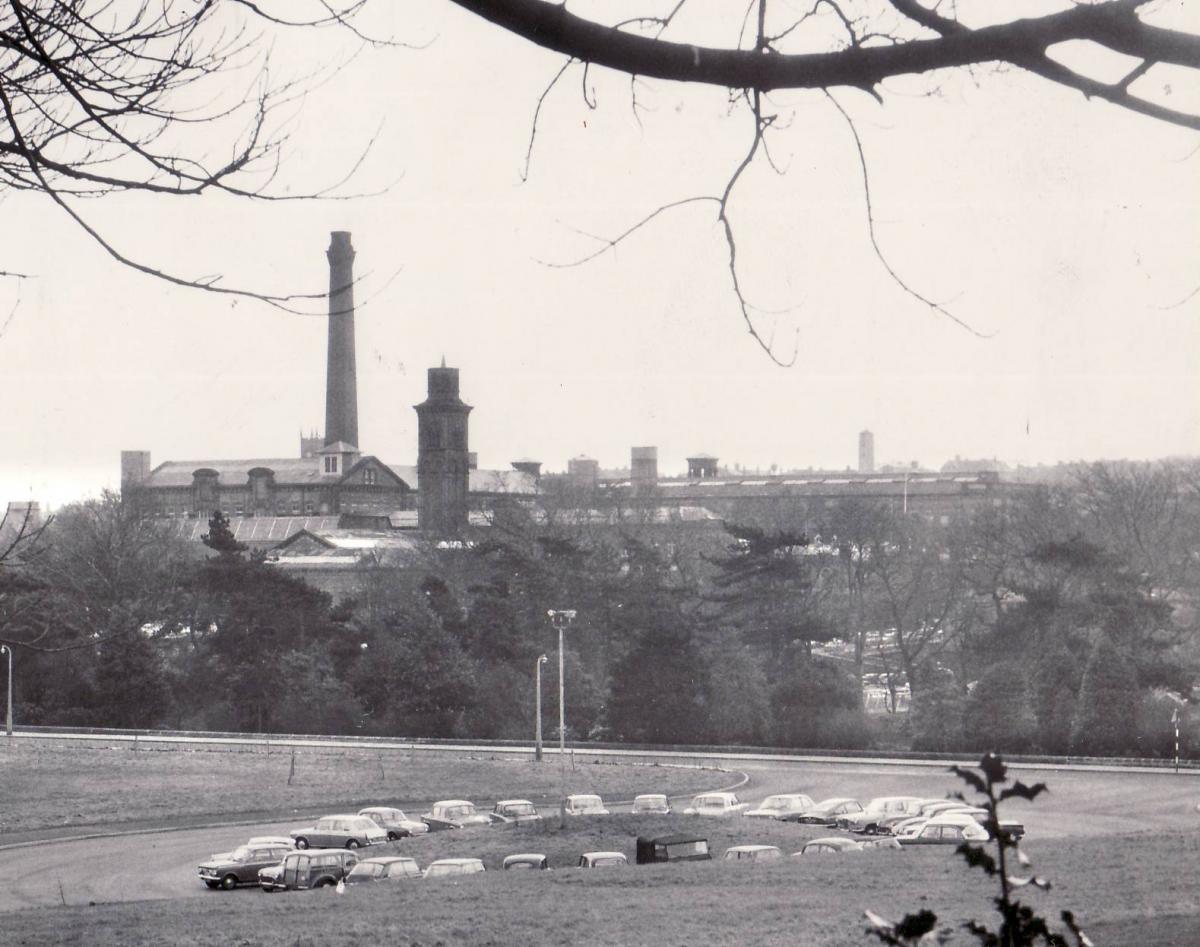

After Mark died last year, aged 77, his surviving son, Matthew, made copies of The Golden Afternoon Fading and a copy was sent to the Telegraph & Argus. In this memoir gave Mark writes about Bradford’s engineering sector at greater length, and considers the closure of textile giants Salts of Saltaire and Lister & Company in greater detail, together with the long-running battle to maintain manufacturing at Black Dyke Mills. He also takes a whistle-stop tour of Bradford’s tea-rooms, restaurants and cafes in the 1960s.

Here we publish the first of several extracts from this remarkable look back at the industrial, business and social life of Bradford.

“It is more than 50 years since my old friend Mike Priestley and I joined the Wool Record as sub-editors. It was December 2, 1962. The city was in the harsh grip of winter and it was a bitterly cold Monday morning. ‘We were the new kids on the block,’ Mike commented years later in his popular column in the Telegraph & Argus.

The Wool Record was a weekly publication established by Samuel Banks Hollings in 1909. As a boy, Hollings had learned about textiles from his father, who owned a flannel-weaving business in Holly Park Mills, Calverley, and took him to the London wool sales. Eventually he became adept at identifying and assessing wools of all descriptions from Britain and overseas. He was 40 when he launched the Wool Record while continuing to act as a wool broker, a newsheet devoted to reports of wool sales and lists of prices and quotations. A year’s subscription was one guinea (21 shillings). It was printed by Percy Lund, Humphries & Co, of Drummond Road, Bradford, and posted to subscribers every Thursday afternoon two hours after the Bradford Market closed. By 1911 it had grown to 12 pages and Hollings agreed to accept advertisements from wool merchants. The business was run from his home in Calverley and an office at No 10 Booth Street close to Bradford Wool Exchange.

Hollings was one of the most popular lecturers at Bradford Technical College, freely sharing his knowledge with local boys training to be wool sorters, and, when the First World War ended, with Australian and New Zealand soldiers who had served on the Western Front and been given six weeks’ leave with pay to attend his talks. He retired in 1936 after selling the Wool Record to Thomas Skinner & Co, a London firm of publishers.

When I joined the magazine it was regarded as the world’s most influential wool-trade journal and occupied offices at 91 Kirkgate. It was one of the most successful trade magazines in Britain, packed with advertisements, and making a lot of money. Its market value was estimated to be £0.5 million (the present-day equivalent is probably around £8 million).

I had previously worked for Hepworth & Grandage, a company I joined after leaving Belle Vue Boys’ whose old boys included not only Mike Priestley but also JB Priestley, my father Tom Keighley, landlord of the Smiling Mule at Eccleshill, and my elder brother, John.

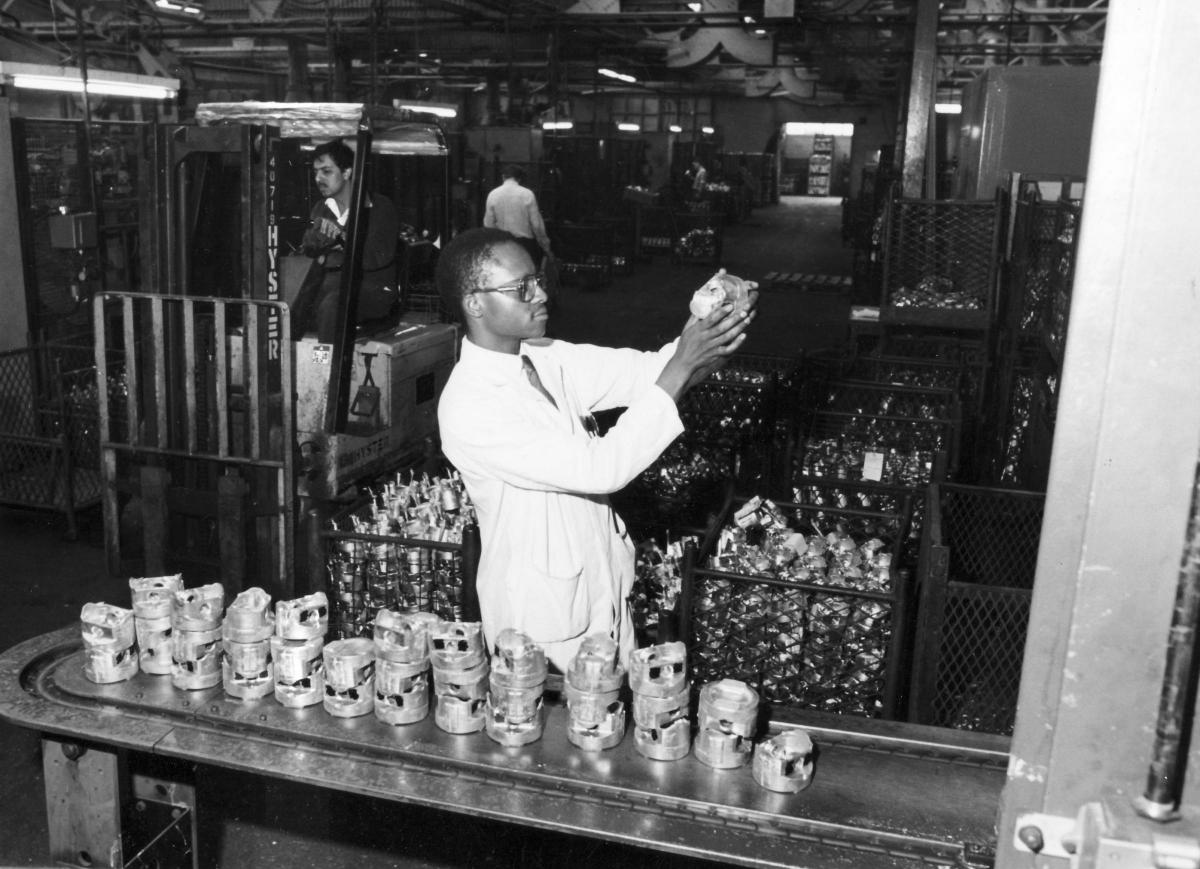

Hepworth & Grandage were one of Bradford’s “Big Three” engineering firms, with Crofts (Engineers) and English Electric. All three were companies of international fame and importance. As editor of The Messenger, the company’s monthly newspaper, I gathered news and information in the vast, noisy production departments at St John’s Works where rough castings were transformed into high-performance pistons and given a mirror finish; piston rings in tens and tens of thousands were ground on special machines costing a fortune; and the atmosphere was redolent with the aroma of lubricating fluids and grease, morning to night. I even had access to the sand-casting and centrifugal-casting foundries so long as I was accompanied by genial Scottish manager J McPherson. Hepworth & Grandage opened an experimental centrifugal casting foundry in 1938 to produce alloy iron sleeves for the manufacture of aircraft piston rings. When war was declared in 1939 it became necessary to build a new foundry for that particular purpose. By 1957, metal was melted in high-frequency induction furnaces then transferred to molten-metal holding furnaces of 12 tons’ capacity, glowing like bonfires in the buildings alongside Neville Road, East Bowling. The entire site throbbed with activity; several thousand people were at work, and many hundreds more in H&G’s plants at Yeadon and Hunslet, and Hirst Wood, Saltaire.

Working at Hepworth & Grandage I met people in every aspect of the business: highly-skilled men making jigs, tools and gauges under the direction of veteran engineer Herbert Swaine; white-coated boffins in the works-study department managed by Allan Rowntree, who later became director of the company’s turbine-blade manufacturing facility on the edge of Yeadon Airport, and eventually the entire Hepworth & Grandage Group.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here