Three brothers, born in Huddersfield in the last decade of the 19th century, came to Bradford with their family (eight in all) some time before 1911.

Archie, Lorrice and Hector Hill all joined up to fight in First World War. Archie came back badly gassed and suffered from respiratory problems until his death at the age of 73 in 1964. Lorrice was badly crippled from bullet wounds to his back, legs and arms and suffered pain until he died in 1963, aged 67.

Hector didn’t come back. He was killed on the Somme in April, 1918, five months short of his 21st birthday.

The family had been eight-strong before the war: five sons, Archie, Lorrice, Hector, Arthur and Allen; one daughter, Ivy; and parents Allen and Mary. He was a car bodywork painter, she was a spinner in a textile mill.

During the war the family left Dracup Road, Bradford, and moved to 57 Halstead Place, Great Horton. It was this address to which various Army forms were posted telling the Hills about their boys.

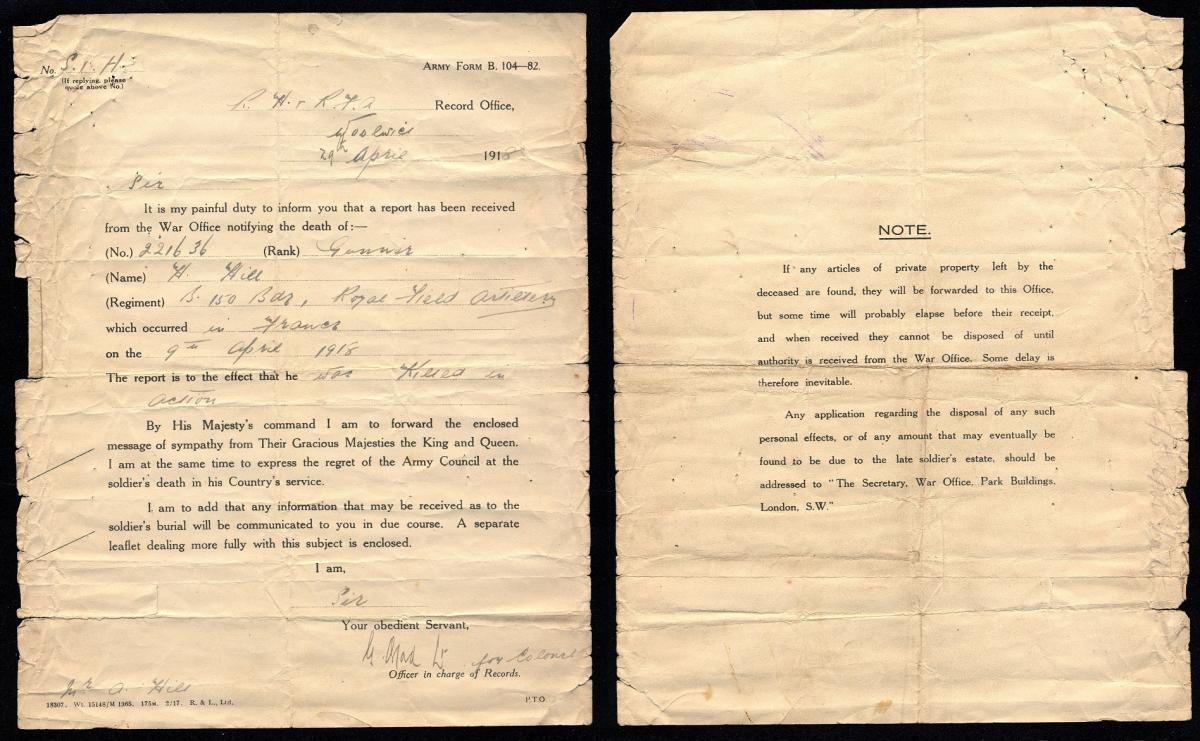

Facsimiles of these forms, at least some of them, were sent to us by Hector Hill, whose three uncles went to war. Mr Hill, who now lives in Settle, North Yorkshire, also sent us a few thoughts on what he called “the bureaucracy of war.”

He wrote: “A war with slaughter and maiming on a vast, industrial scale clearly needed an equally vast, and industrialised, bureaucracy to process the associated paperwork.

“In reviewing the documents relating to two of my uncles (one killed, the other paralysed) my eyes were drawn to the printed codes in the corners of the page.

“These weren’t letters; they were official forms tailored to their life-devastating purpose, with formally structured sentences and dotted lines at appropriate points where the foot-soldiers of a small, desk-army would write the details of the victims and the names and addresses of the next of kin, who were victims in their turn.

“It is quite chilling to contemplate the printing presses of His Majesty’s Stationery Office (HMSO) churning out hundreds of thousands of these blank forms, to be brown-paper-parcelled in reams and transported to stationery stores and on to stationery cupboards and thence to scores of desks where clerks wielded their pens.

Army Form B. 104-82 beginning with the phrase, ‘It is my painful duty’ brought news of death with the name, number, rank, regiment, where and when being handwritten.

“There followed a printed paragraph of His Majesty’s appreciation, etc; and the final paragraph made mention of future notice of burial arrangements. On the reverse was a two-paragraph notice relating to the handling of personal effects.

“That devastating letter came in an envelope. Army Form B. 104-121 did not. Its dotted lines carried information about the burial location. On the reverse, it had printed marks to guide the clerk as he folded it in three. The centre panel was printed with On His Majesty’s Service, a round Official Paid stamp, and dotted lines for the address of the next of kin.

“In the years after the war, many bodies would be disinterred and aggregated in military cemeteries, or designated parts of civilian cemeteries, as part of ‘an agreement with the French and Belgian Governments to remove all scattered graves... and... cemeteries containing less than 40’.

“This news arrived on Form B3; a sheet of foolscap paper that had passed through a spirit duplicator (teachers and pupils of the pre-photocopier area will recall it as ‘The Banda’).

“Army Form B. 104-80 was an HMSO printed letter carrying news of a loved-one being wounded. At the top right there were dotted lines for the address of the sending office and the date.

“By 1917 it received a just cursory oval stamp and a hand-written date; like issuing a vehicle licence at the Post Office. It didn’t merit an envelope, nor even OHMS and Official Paid. The clerk was left to fold it approximately in three, write the address and use a postage stamp to hold it closed.

“The role of telegrams would bear some consideration. Even as a child in 1950s back-to-back Great Horton, one could sense the tension in the air whenever a GPO telegram delivery man’s moped passed along the street.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article