We have already seen in previous weeks that boys under the age of 18 who were determined to join the Army in 1914 either lied about their age, gave a false name, or in some cases did both.

In those days, when boys legally became men at the age of 21, a volunteer could take the King’s shilling at the age of 18, but was not supposed to go abroad and fight until the age of 19.

Yet historians believe up to 250,000 boys joined up in the belief that they would give the German military machine a good bashing, put the Kaiser in his place and then return home before Christmas to carry on as normal.

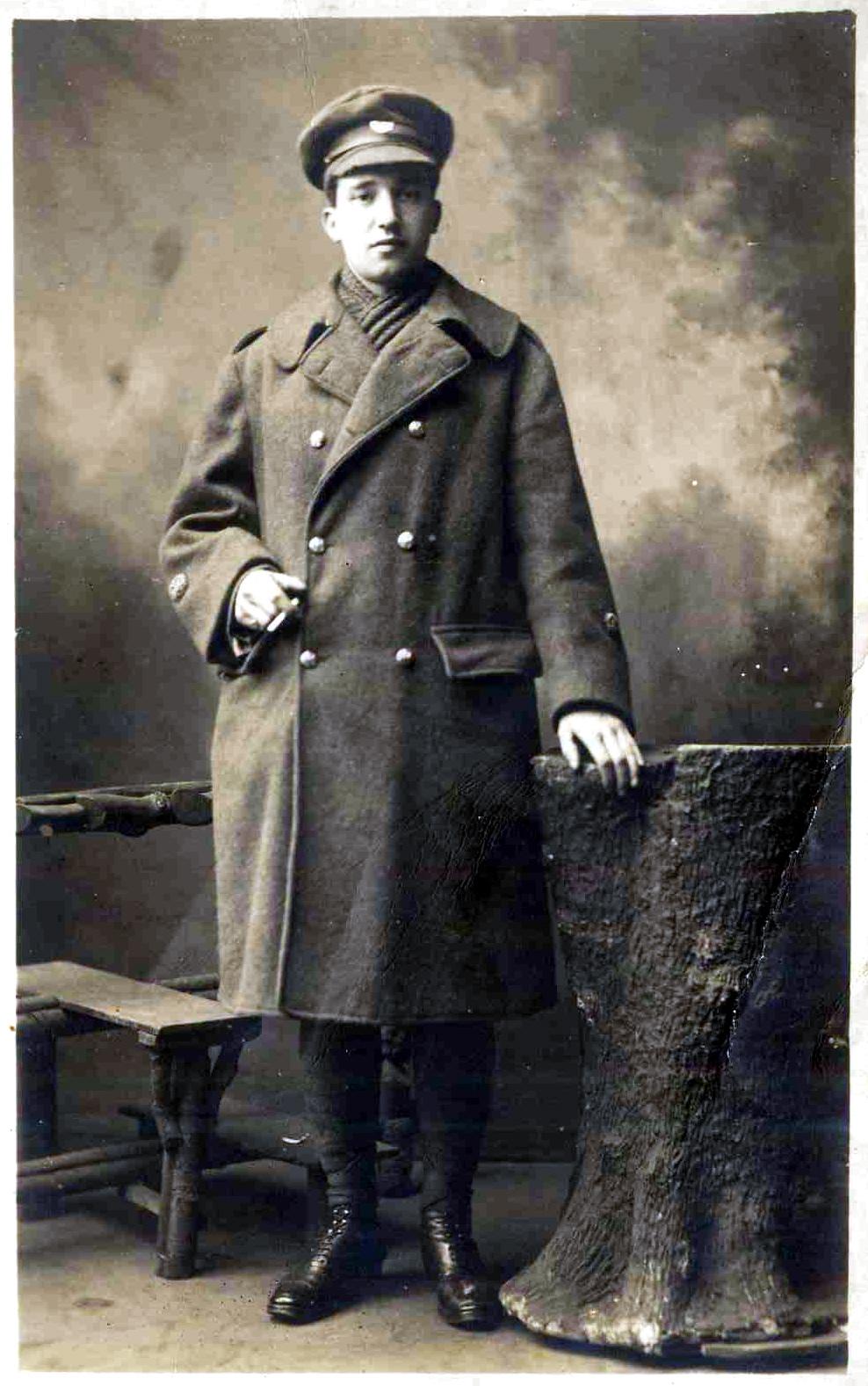

Thousands of them didn’t come back. One of them was 19-year-old Maurice Hudson, one of five brothers who lived at 18 Whetley Grove, Manningham, Bradford, the home of William Hudson, a wool merchant in Nelson Street, and his wife Hannah. There were five boys aged between 21 and four.

The 1911 Census states that Maurice was a 12-year-old schoolboy. He died of wounds on the Western Front in January, 1918 at the age of 19. The inference is that he was one of the under-age boys who volunteered before conscription was introduced in 1916. Conscripted recruits were obliged to provide proof of identity.

Mrs Madeline Schofield, of Oakworth, is a surviving niece of the Hudsons. She believes Maurice joined up under age. Perhaps he did so after two of his big brothers, Herbert and William, joined the colours.

Brothers joining up was an extension of the ‘Pals’ ethos encouraged by the military authorities. They believed that soldiers would fight harder and longer if their comrades-in-arms were friends or from the same area.

Not forseeing the nature of the war to come, they did not ponder the consequences for families and areas such as Bradford, Leeds and Manchester in the aftermath of mass slaughter.

Tricia Platts, secretary of the Bradford World War One Group, has dug out the following information about the fighting Hudsons and their units. She writes: “The Yorkshire Dragoons were a new Territorial Regiment formed in 1908 and with four Squadrons based at Sheffield, Wakefield Doncaster and, D Squadron at Huddersfield/Halifax.

“In June 1915, D Squadron was dissolved and the men dispersed among other units. 1/4th Hallamshires were a Sheffield Territorial Battalion. They were the 148th Brigade within 49th West Riding Division, thus Maurice would have served close to his older brother William who was a Bradford Territorial in 146th Brigade of the same Division.

“The Medal Card for Herbert shows that he went abroad on September 11, 1915, as a Sergeant in King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry and was later transferred into the Machine Gun Corps (MGC) and became Regimental Quarter Master Sergeant. His training as a clerk in a Bradford yarn merchant's office would have been good training for this.

“In 1914, infantry battalions were equipped with a machine gun section of two guns, which was increased to four in February 1915. The sections were equipped with Maxim guns, served by a subaltern and 12 men.

“The obsolescent Maxim had a maximum rate of fire of 500 rounds, so was the equivalent of around 40 well-trained riflemen. However, production of the weapons could not keep up with the rapidly expanding army and the British Expeditionary Force was still 237 guns short of the full establishment in July 1915.

“The British Vickers company could, at most, produce 200 new weapons per week, and struggled to do that. Contracts were placed with firms in the USA, which were to produce the Vickers designs under licence.

“On September 2, 1915, a definite proposal was made to the War Office for the formation of a single specialist Machine Gun Company per infantry brigade, by withdrawing the guns and gun teams from the battalions.

“They would be replaced at battalion level by the light Lewis machine guns and thus the firepower of each brigade would be substantially increased. The Machine Gun Corps was created by Royal Warrant on October 14 followed by an Army Order on October 22, 1915.

“Shortly after the formation of the MGC, the Maxim guns were replaced by the Vickers, which became a standard gun for the next five decades.

“The Vickers machine gun is fired from a tripod and is cooled by water held in a jacket around the barrel. The gun weighed 28.5 pounds, the water another ten and the tripod weighed 20 pounds.

“Bullets were assembled into a canvas belt, which held 250 rounds and would last 30 seconds at the maximum rate of fire of 500 rounds per minute.

“Two men were required to carry the equipment and two the ammunition. A Vickers machine gun team also had two spare men.

“There are many instances where a single well-placed and protected machine gun cut great swathes in attacking infantry. Nowhere was this demonstrated with more devastating effect than against the British army’s attack on the Somme on 1 July 1916 and against the German attack at Arras on 28 March 1918.

“William Hudson was in D Company of the Bradford Territorials. He landed at Boulogne on April 16, 1915, and appears to have served throughout the war with them. It is likely that William would have been captured on April 25, 1918, during the German attack on positions at Kemmel Hill.”

Mrs Schofield said his family back in Bradford thought William had been killed. In fact, he was taken prisoner after his unit ran out of ammunition near Wytschaete, on the Ypres front in Belgium.

William Hudson’s D Company got cut off and were surrounded by enemy soldiers. What was left of the Battalion of Territorials held on to seemingly hopeless positions and prevented the Germans from capturing the village of Vierstraat.

Tricia said: “In the evening of April 25, orders were given that all survivors should assemble at Ouderom, but with units spread out across a wide area of a badly-shelled battlefield it was some time before the order was heard by all.

“It would be many months before accurate casualty figures could be established. It was estimated that, in the 6th Battalion, 22 officers and 457 other ranks were missing, wounded or dead.”

Mrs Schofield said: “For the last eight months of the war, Willie was helping to serve soup in kitchens and managed to survive.”

His brother Herbert, who had transferred to the Machine Gun Corps, also survived the war (he died in 1948). He came out of it with a Belgian Croix de Guerre, though why it was awarded is not known. Tricia Platts said in these columns several weeks ago that foreign medals were sometimes given out to British troops fairly randomly.

Unlike his older brothers, Private Maurice Hudson, of the 1/4 Hallamshire Battalion, the York and Lancaster Regiment, did not survive. He was died on Sunday, January 20, 1918. He was buried at Roclincourt Military Cemetery, Pas de Calais, Northern France.

During World War 1 the York and Lancaster Regiment recruited about 57,000 men. Of these, 72 out of every 100 were either killed or wounded. Fatalities totalled 8,814.

The records of Private Hudson’s battalion are currently being digitised at the National Archives in Kew and will be available online after next Monday, May 19, by typing in the code W095/2805/1 under the heading discovery catalogue.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article