For more than 80 years, from the early 1830s until 1914, people of German origin had been a feature of Bradford’s commercial, cultural and civic life.

Little Germany, Heidelberg Road, Mannheim Road and latterly Hamme Strasse: these names form a layer in Bradford’s anthropological geology. Jacob Behrens from Hamburg arrived in 1832. By 1902 there were, reputedly, 52 German textile merchants buying and selling raw materials and finished products in the city.

One of them was Julius Delius, who became a prosperous wool merchant as well as a prolific begetter of children. He and his wife Elsie had 14, the fourth of whom they named Frederick. We know him better simply as Delius, the composer.

Another of them was Frederick Gerhartz, a stuff merchant who lived with his wife, three sons and two daughters, at 8 Clifton Villas, off Manningham Lane. That was an area of the well-to-do in those days.

On the afternoon of Wednesday, August 4, 1914, according to the next morning’s Yorkshire Observer, he was crossing Manningham Lane on his way home to lunch when he was hit by a tram and knocked violently to the ground.

He recovered sufficiently to return home, but at 6pm that evening, an hour before Britain declared war on Germany, this genial man “of fine presence and affable manner” died of a brain haemorrhage.

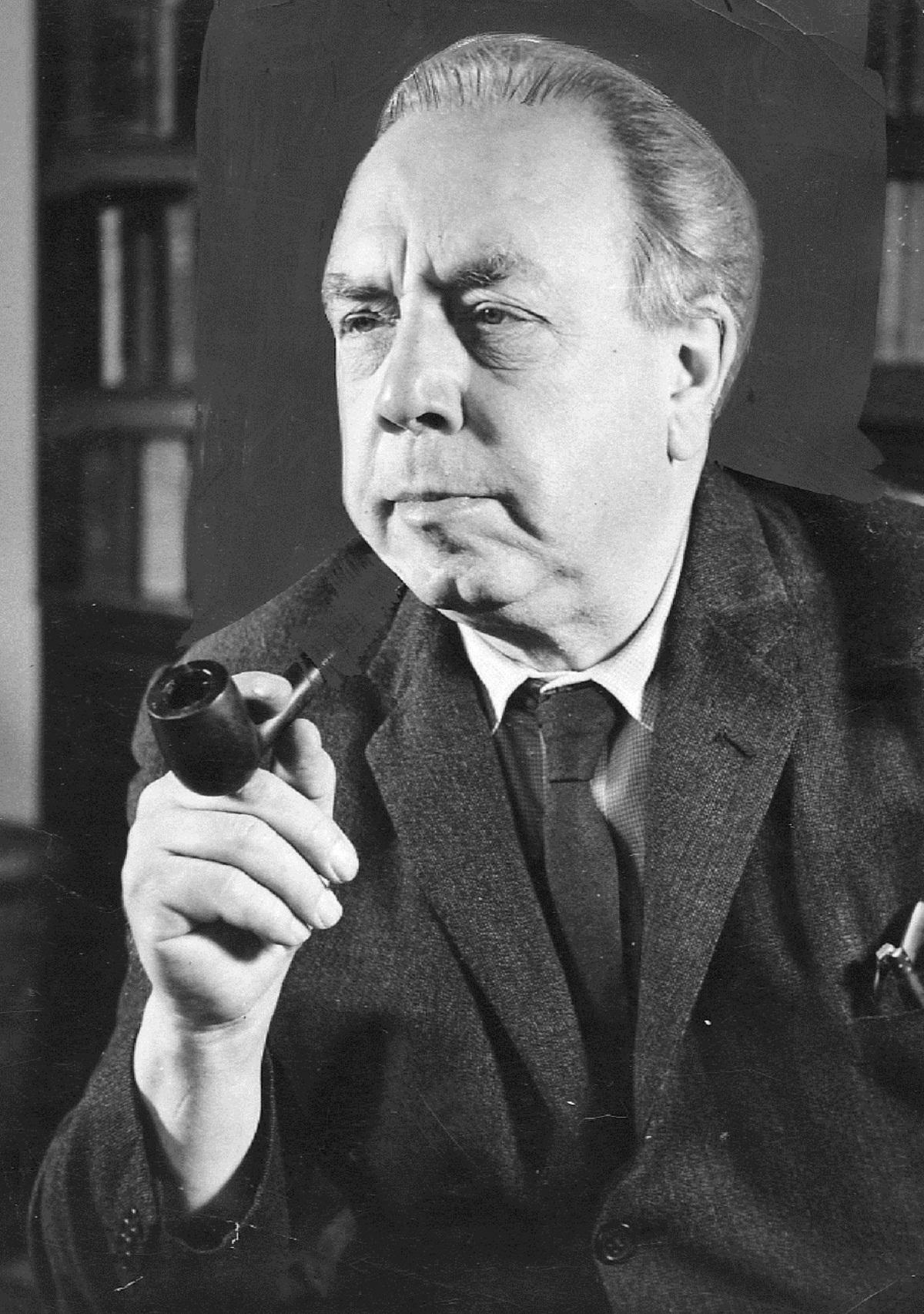

Bradford-born writer and broadcaster J B Priestley, who was born at 34 Mannheim Road, Heaton, in 1894, said the presence of mostly affluent German-Jews in Bradford was so common he never thought to ask why they were here.

“I saw their outlandish names on office doors, knew they lived in certain pleasant suburbs, and obscurely felt they had always been with us and would always remain,” he wrote in his book An English Journey.

“That small colony of foreign or mixed Bradfordians produced some men of great distinction, including a famous composer, two re-nowned painters and a well-known poet. (In Humbert Wolfe’s Now A Stranger you get a glimpse of what life was like in that colony for at least a small boy).

“I can remember when one of the best-known clubs in Bradford was the Schillerverein (on Rawson Square off Manor Row, from 1862 until 1910). And in those days a Londoner was a stranger sight than a German.

“There was, then, this odd mixture in pre-war Bradford. A dash of the Rhine and the Oder found its way into our grim runnel – ‘t’mucky beck’. Bradford was determinedly Yorkshire and provincial, yet some of its suburbs reached as far as Frankfurt and Leipzig. It was odd enough. But it worked.

“The war changed all that.”

On July 17, 1917, the war caused King George V to change the royal name from the House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to the House of Windsor. According to the book Bradford In The Great War, by the Bradford World War I Group, that step was also taken in Bradford.

“...when war was declared in August 1914, Germans became the enemy and, inevitably, attitudes changed and respected citizens became aliens overnight.

“The swimming baths complex in Morley Street /Great Horton Road, originally called the Kursaal, changed its name to become the more patriotic Windsor Halls comprising Kings and Queens Halls.”

Young visiting German reservists left Bradford by train to return, via London, to their regiments. Reportedly, a German band played at the station, which “was not popular”.

“...by August 10, over 20 ethnic Germans had been taken to the new military prison at Bradford Moor Barracks. The 1914 Aliens (Restrictions) Act was intended to prevent German spies from infiltrating the state. It required the ethnic German population of Bradford to register with the authorities.

“Approximately 300 out of the estimated 500 German population registered their names, addresses, ages and occupations. They were restricted in where they could travel and had to report regularly. Under the Act, the deportation of aliens was permitted.

“After the sinking of the Lusitania in April 1916, anti-German feeling entered a new phase. For example, women at Manningham Mills refused to work with German colleagues, who were promptly sacked. The expedience arising from a full order book outweighed the necessity for any kind of legal process.

“Major injustices were matched by minor pettiness. German bands were banned from playing in public parks, German language classes were removed from schools and street names were changed.

“Around 139 German residents escaped internment. Some anglicised their names (following the example of the royal family) and kept a low profile for the duration of the war.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article