JIM GREENHALF on the Bradford soldier who rose through the ranks to lead his battalion to battle success in the First World War

One of the many Bradford young men who joined up in 1914 – Britain had a volunteer army then, conscription was introduced in 1916 – was Harry Hartley.

Remarkably, he served throughout the years of the First World War, rising from the rank of private to a commissioned second lieutenant.

He was born on July 3, 1889, to Thomas and Hannah Hartley of 74 Undercliffe Street, which no longer exists. The family moved to nearby 118 Newlands Place.

Harry was a travelling salesman for the Bradford textile firm of Richardson and Hartley on Fountain Street. His job required him to journey extensively in Germany, Poland and perhaps pre-revolutionary Russia. He spoke German fluently and won a tennis tournament in Germany in 1913.

His talent for tennis was passed on to his granddaughter Catherine, who was eight times Yorkshire tennis champion.

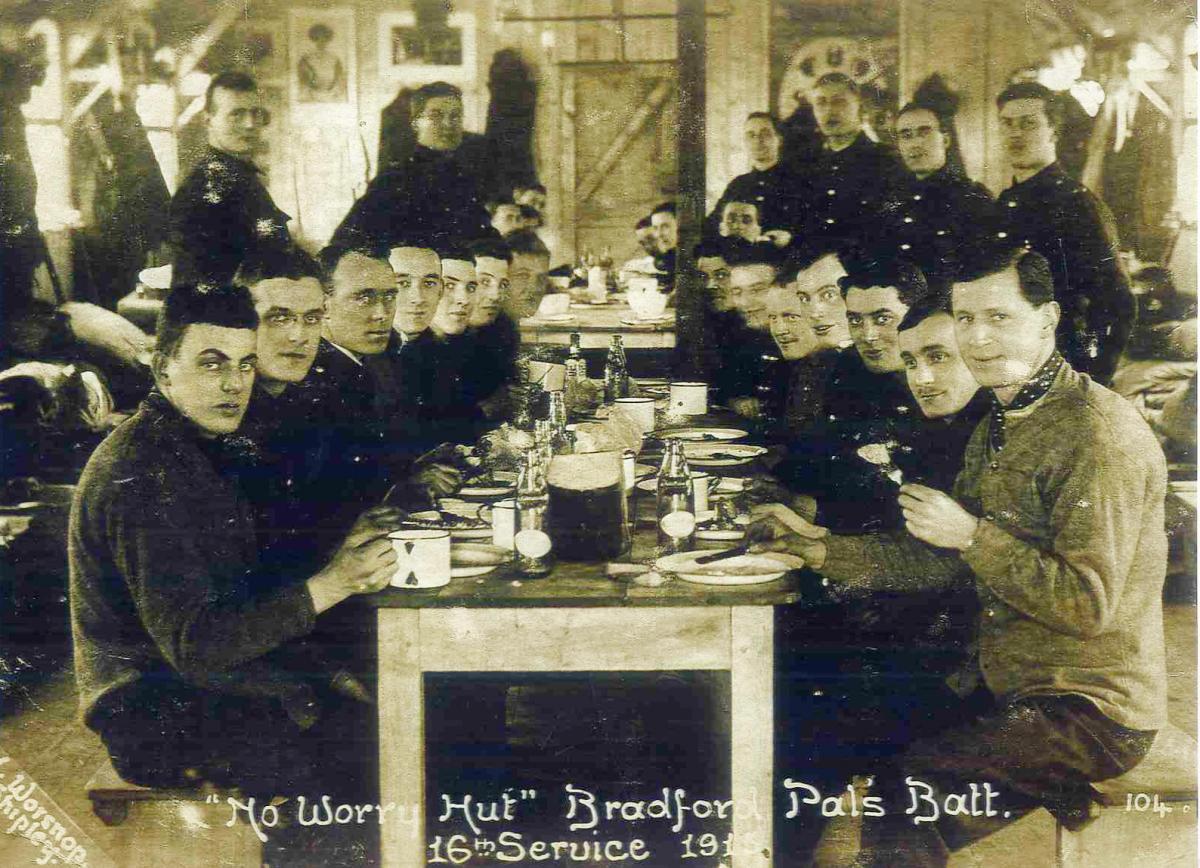

Harry joined up in 1914 as a cadet, then as a private in the Bradford Pals 16th Battalion. In 1915 he was sent to Port Said to protect the Suez Canal. From there he was shipped to France and saw action at Neuve Chapelle in March 1915.

After the Battle of the Somme in the summer of 1916, he received a commission as second lieutenant in the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment.

Wounded badly enough to be given ten months’ leave between December 1, 1917, and September 18, 1918, he was thought to have been killed in the German spring offensive of 1918.

A telegram of condolence on behalf of King George V was dispatched from Buckingham Palace on April 30, 1918, to 118 Newlands Place, Bradford, the home of Harry’s parents Thomas and Hannah.

“My death certificate”, he later printed across the telegram. Gallows humour was necessary for survival in the frontline trenches of France and Belgium. Not for nothing were they known as “suicide ditches” by Harry and his pals.

But Harry survived and after the war in 1920 returned to Germany until the outbreak of the Second World War.

He married Phoebe Anne Crabtree in 1922. They had a daughter, Freda, in 1925.

Freda married Kenneth Berry in 1947 and they had three children.

Michael Berry, 62, a retired school teacher of history and the classics, mainly in Lincolnshire, lives in Bradford; Keith Berry, 58, who works for a shipping company in Glasgow; and Catherine, 48, lives in Southampton and runs a marketing company.

Harry’s war memorabilia includes service medals, a waterproof trench map of the Cambrai area showing German positions marked in red, birth and death certificates, and a pencil-written letter home to his family dated November 25, 1917.

There are facsimiles of battlefront notes, a green-backed notebook of lecture notes written in pencil between April 9 and July 11, 1917 – which Michael thinks were made either in Lichfield or South Shields, before Harry was sent out to the Western Front – photographs, a bank book, his Army paybook, passport documents and drawings.

Why did he keep them?

“The horrors of war, how he managed to survive four years of terrible conditions,” Michael said. “He was a keen supporter of Yorkshire County Cricket Club, he was a member. We used to meet up at Headingley on occasion, but he didn’t talk about his experiences.”

Michael said his grandfather used to get into rages and rant in German. None of this is apparent in the jaunty letter dated November 25, 1917, that Harry sent home to his family four days after the British offensive at Cambrai in which he took part.

“We came out of the line yesterday morning. I had been four days without any sleep. We went up to the line early Monday morning arriving there just before dawn,” Harry wrote.

“We didn’t half scatter the Germans, taking thousands of prisoners. You will be proud to hear that I took my company over the top Tuesday morning and gained our objective, which was about six-and-a-half miles deep into Boche territory at 4.20. We had a very rough time...

“It was absolutely the best advance there has been by the British since war commenced. I think we took as much Boche territory in 12 hours as we did in 12 weeks on this front when we started the attack in July last year [referring to the Battle of the Somme].

“Well, I had a charmed life. They didn’t seem as though they could possibly hit me. We were fired on by their artillery at less than 200 yards, but the shells eventually went over our heads (only just). We had about eight officers knocked out but none of them were very bad. I think they will all live.

“I led the company back to where we are now – a small village behind the line. As company officer I had the privilege of a horse to ride, but preferred to walk with the lads.

“Well I could write on but have very little time. If anyone asks you how I am getting on, tell them A1. I was tired last night but couldn’t sleep for a headache from the guns.

“I think Sir Douglas Haig is jubilant. It is real fine here now as long as it keeps up. Better than staying in one place and manning the trenches for weeks on end. It’s much more exciting killing them.

“We are now standing ready to go at a half hour’s notice so will close. I hope I am as lucky next time. Send my love to you all. Yours affectionately, Harry.”

He died in York at the age of 85 in December 1974. For 34 years he had lived in an ex-serviceman’s home, The Retreat, in York, where he had gone in 1940 suffering from the long-term effects of shell-shock.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article