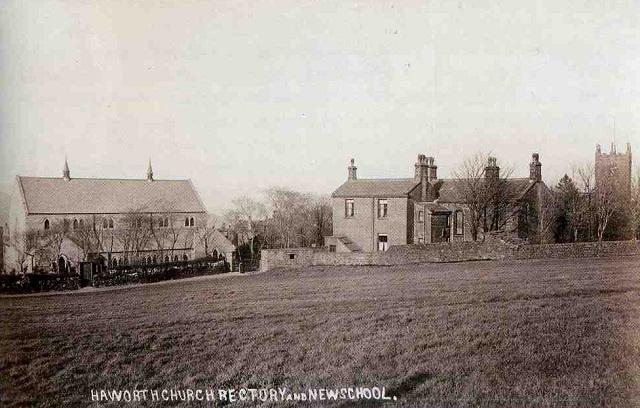

In the words of Charlotte Bronte’s biographer Elizabeth Gaskell, it is a “low, oblong stone parsonage, high up, yet with a higher backdrop of sweeping moors”.

Today Haworth Parsonage is a world-famous literary shrine. Thousands of tourists visit the house, now the Bronte Parsonage Museum, to discover what inspired Emily, Charlotte and Anne.

Yet it is often forgotten that the parsonage has also been home to several other families, before and after the Brontes.

Following Patrick Bronte’s death in 1861, it was occupied by four of his successors at Haworth’s parish church then, when the Bronte Society bought the building in 1928, it became home to four custodians and their families, who witnessed the growth of tourism in Haworth.

A new collection of photographs and artefacts, on display at the Bronte Parsonage Museum until the end of this year, reveals the secret life of the building through the stories of those who lived there. Called Heaven Is A Home, it also uses letters, sketches and documents to detail domestic details of the Brontes’ residence.

The exhibition complements the Parsonage’s recent £60,000 refurbishment. Decorative historian Allyson McDermott used forensic analysis on tiny samples of paint and paper left from the Brontes’ time to recreate a decorative scheme close to that of their residence.

Also linked to the exhibition is At Home With The Brontes by Ann Dinsdale, collections manager at the museum, tracing the history of the house and those who lived there, from a horsewhip-wielding minister to a sitcom actor’s daughter.

Ann had the idea for a book a decade ago when she met Trevor and Eric Mitchell, whose father was Harold Mitchell, the Bronte Parsonage Museum’s first custodian.

“I got to know Eric well and was fascinated by his stories of growing up at the Parsonage,” says Ann, who also met former curator Joanna Hutton and Jean Bull, whose father was the last live-in custodian.

With the support of the Mitchells, Jean and the family of Joanna, who died in 2002, and using a variety of mostly unpublished sources, Ann researched the Parsonage inhabitants, bringing their stories to life.

“I no longer think of the Parsonage only in association with the Brontes,” she says. “Its rooms are now peopled by all those others who have lived in the house – this is their story.”

As well as exploring the impact of the house on the sisters’ writing, and what it was like for their successors living in a literary shrine, Ann traces the occupants who lived there before Patrick Bronte’s incumbent as minister of St Michael and All Angels Church in 1820.

The house was built in 1778, but Ann’s book begins 40 years earlier, with the arrival of the Reverend William Grimshaw, a leading light in the 18th century Evangelical Revival.

He brought fame to Haworth nearly 100 years before the Brontes, thanks to colourful accounts of him “haranguing sinners and driving his parishioners from public house to church, brandishing a horsewhip”.

There was no official parsonage at Haworth until the arrival of Grimshaw’s successor, the Reverend John Richardson. The Parsonage, or Glebe House as it was known, was built of millstone grit, quarried from nearby moors.

After Richardson came Reverend James Charnock, and following his death, Henry Heap, Vicar of Bradford, nominated Patrick Bronte, Perpetual Curate of Thornton, as his successor.

Patrick moved in with his family in April, 1820, and the following year, his wife Maria died of cancer. In later years, Charlotte remembers her mother “in the evening light, playing with her young son Branwell in the Parsonage dining room”.

Ann describes in detail the layout of the Brontes’ home, drawing on Charlotte and Patrick’s accounts of domestic life.

Tourism came to Haworth in the aftermath of Charlotte’s death, when Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography created a buzz of interest in the Brontes’ lives. Patrick’s home attracted a stream of literary pilgrimages, and he occasionally cut Charlotte’s letters into snippets for visitors!

Patrick was succeeded by rectors John Wade, Thomas Story, George Elson – who was there when the first film of Wuthering Heights was shot in Haworth, drawing great crowds – and John Crosland Hirst. When the Bronte Society acquired the Parsonage in 1927, the Hirst family reluctantly left their home for a new rectory.

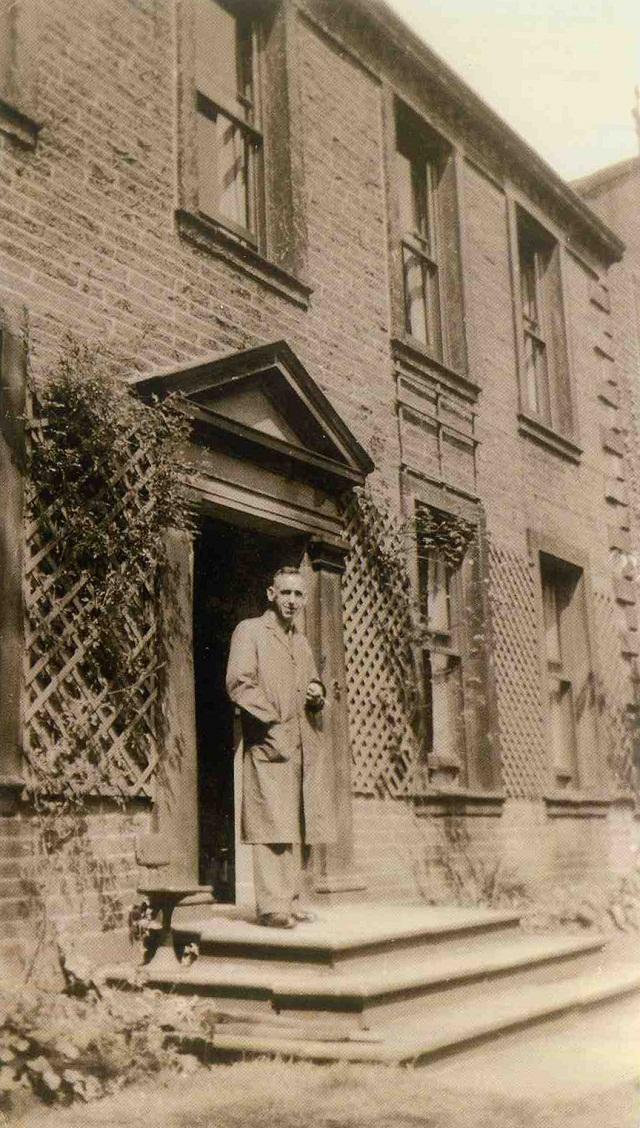

Harold Mitchell, a 32-year-old ex-serviceman, was appointed first custodian for the museum, which was drawing around 4,000 annual visitors. Harold sold postcards and souvenirs in the old kitchen and his younger sons Trevor and Eric were born in the Mitchells’ living accommodation, separated by a glass-panelled door.

“Bringing up three boys in a literary shrine must have been difficult,” writes Ann. “Noisy games had to be curtailed and, from an early age, the boys were very conscious of what they called ‘the family next door’.”

The family kept a pet owl in the kitchen, and Eric recalls meeting famous visitors at the museum, including Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles and Daphne du Maurier. One of his earliest memories was being photographed on the Parsonage steps with James Roosevelt, son of the American president.

During the war, the Parsonage remained open – films such as the 1939 Wuthering Heights adaptation starring Laurence Olivier fuelled Brontemania – and troops stationed at Haworth Sunday school would use the Parsonage bathroom.

Eric remembers “small groups of soldiers congregating in the sitting room, waiting for a bath”.

In 1961, Harold Mitchell retired and new curator Geoffrey Beard moved into a flat behind the Parsonage with his young family. They lasted just 18 months, leaving the Bronte Society facing a security crisis.

Enter 30-year-old Joanna Hutton, who first visited the Parsonage as a child. Born into an acting family – her father, Arthur Brough, was Mr Grainger in Are You Being Served? – she prompted colourful press reports of a “young actress” at the Parsonage. One newspaper letter-writer likened her appointment to “putting Brigitte Bardot in charge of the house of Victor Hugo”.

Living on the premises, Joanna was never off duty and visitors regularly turned up out of hours. One such visit took place at 9pm after a busy day. She recalled: “There was a knock on the kitchen door. On my way to answer it, I said: ‘if it is the dear Queen herself I will not let her in’. I opened the door to see an elegant gentleman, dressed in navy blue with a pink satin cravat silhouetted against the dustbins. He said: ‘I am a photographer. My name is Beaton. Please could I see the museum?’ I ran to open the gate, shouting ‘It’s not her Majesty, just her photographer!’”

In 1968, Joanna left the Parsonage and set up the museum bookshop on Main Street. Her successor was Norman Raistrick whose appointment coincided with the busiest period in the museum’s history, thanks partly to 1970s TV programmes, including Blue Peter, filmed there. The house also appeared in 1970 film The Railway Children.

Norman retired in 1981 and the custodian’s flat was converted into an office. The 1980s marked a period of change at the Parsonage, with a new exhibition space and a focus on presenting the house at it was in the Brontes’ time.

Do any past inhabitants still linger in the house?

Asked if it was haunted, Norman Raistrick smiled. His interviewer recalls: “Yes, he really did close the downstairs shutters every night and never neglected to say ‘Goodnight Mr Bronte’, but, he chuckled, ‘Mr Bronte never answered back’.”

Ann Dinsdale will discuss the history of Haworth Parsonage and its occupants at the Bronte Parsonage Museum on Wednesday, June 26, at 7pm. Tickets are on (01535) 640188. At Home With The Brontes: The History Of Haworth Parsonage And Its Occupants, by Amberley Publishing, is £14.99.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article