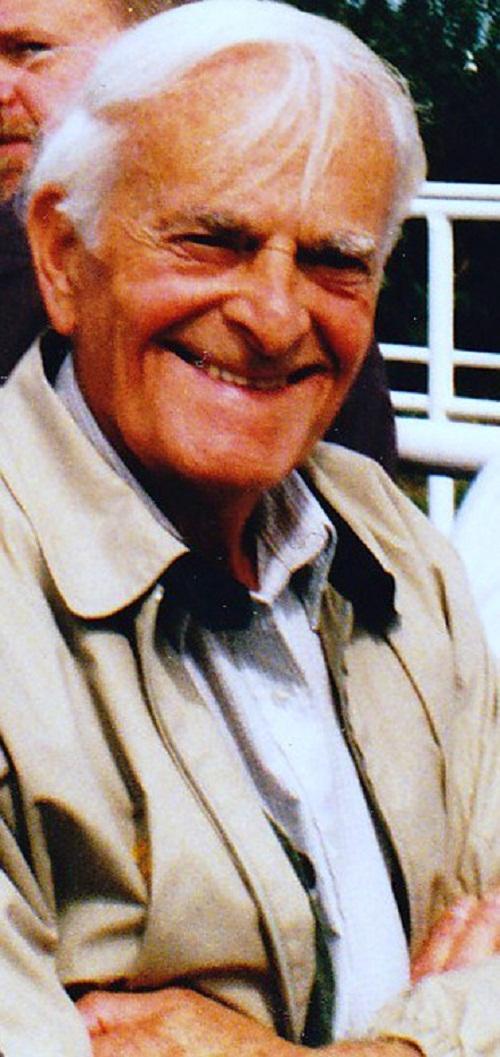

This article was first published in February 2013. We republish it today following the news that Harry Leslie Smith has died aged 95.

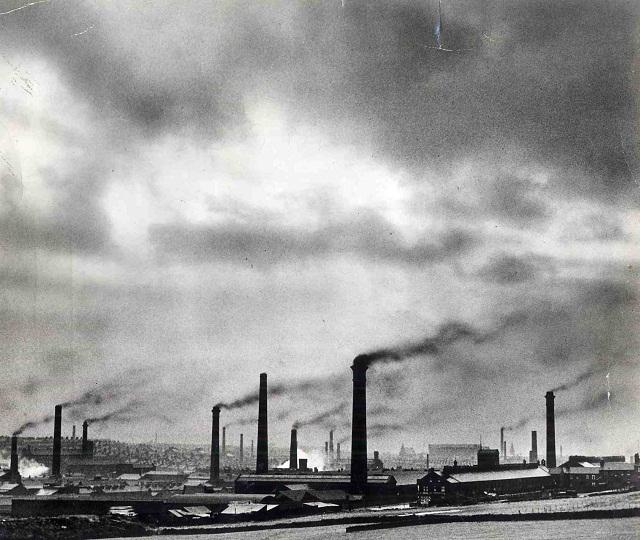

Bradford during the Great depression of the early 1930s was a grim place to be if you were without work and money.

Harry Leslie Smith’s account of his early life in Bradford would not be out of place in Robert Tressell’s The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists or Howard Spring’s Fame Is The Spur.

“It was under the cover of darkness that my family came to Bradford from Barnsley during the era that followed the General Strike. We entered this city of bright gas lights after my father, a miner, was made redundant.

“Like the rest of the country’s unemployed, we took our chances and hoped guile and good fortune would lead us from the darkness of poverty towards the safety of a steady income.

“Yet, there was something else that spurred my family towards Bradford; it was my mum’s inability to accept defeat. She wasn’t prepared to lie down and let the tides of fate drown her and her brood.

“The pawnshop might own her best dresses, wedding ring and bedroom furniture, but she refused to barter away her determination to survive.

“With cunning and sex appeal, my mother insured that when we arrived in Bradford that there would be a roof over our heads and some spare shillings to keep us fed. She cajoled a landlord into letting her take charge of a doss house in exchange for free rent and a small stipend.

“To my young eyes, the outside of house looked sinister and decrepit, while the interior was ripe with the heavy smell of unwashed bodies and cheap tobacco. I clung close to my father’s side as we moved into our one-room squat while my mother whispered brave cliches that this was better than the work house.

“My mother was always good at putting on a brave front at the beginning of our downward spiral, but it didn’t fool me. All I had to do was look at the taciturn, worried faces of the other tenants.

“We were now citizens of a society inhabited by people in constant poor health, pursued by bailiffs and who were never going to have the brass to buy their way out of purgatory.

“Sometimes a down and out veteran of the Great War, with a game leg or gassed lungs, would show up at the front doorstep and beg admission from my mother. I’d hover behind her as she advised him of the cost to kip in this house.

“Once, I witnessed an elderly couple arrive holding a lifetime of toil in a cheap cardboard suitcase. The look on their faces was resigned, as if they knew that despite how much promise their life might have started out with, it was going to end in a dirty, dark room infested with bugs.

“For a while, a mad woman even occupied a room. On my way to play, I’d hear her chatter to unseen ghosts behind thin white-washed walls. She sounded like a dog made senseless by cruelty.

“Her faithful husband was the only one able to pacify her by speaking softly into her ear and afterwards placing cubes of sugar into her toothless mouth.

“While my mother commanded the lives of those lodged in this wretched house and flirted with the fit, Irish workers, my father escaped this harsh new reality by taking long walks across Bradford.

“He hoped that on his travels he’d find another job, but there were no positions for a sensitive miner too old for the pits and too young for the grave.

“Short of money, my mother accepted the harsh generosity of St Vincent de Paul’s to clothe her children. We now wore the uniform of mendicants: rough hewn corduroy trousers for boys and heavy smocks for girls.

“My father found me crying one day, for our lost life, and tried to dispel my terror by letting me ride on his shoulders, while we walked to a stall that sold mushy peas for a penny a plate.

“To remind us that there was beauty, even in this city of looms, grit and grime, he took us to Manningham Park.

“On the day we went, it didn’t matter to me how dusty and desperate we looked, because for a few short hours we were free from the doss house and its misery. My sister and I scampered and scattered across the lawns. We climbed on top the stone cylinders that dotted the sides of the walk way.

“As the financial conditions of the world grew more severe, my mother lost her position at the doss house and we were compelled to move into more squalid digs. At the age of seven, I was put to work as a beer barrow boy.

“With my cart stacked high with ale, I trundled through dusky streets, where gas lights sputtered and cast long shadows into dark alcoves; while all around me the Great Depression lay siege to the North and to England’s humanity.

“My dad was older than my mother. He was born in 1867 which she was born in 1896. They were married in 1914, the day after the assassination of the Arch Duke Ferdinand. They really didn't have a lot luck with anything.

“His marriage ostracised him from his family who were publicans in Barley Hole, outside of Rotherham. While in Bradford, my mother took up with a navvie which produced my half-brother.

“She was just looking for someone who could provide for her and her children. However, the navvie was not her man but she did find a cowman who, although brutal and rather useless at earning money, loved her in his fashion.

“They took up together, but my dad was skint so he was relocated to an attic where my sister and I slept. After awhile, he was forced from the doss house and lived alone in a room at another house in St Andrews Villas until he died in 1943 at St Luke’s Hospital.

“My mother, sister, brother and another brother from the cowman ended up in Halifax. When my sister left school, she moved back to Bradford in the late 1930s and got a job in a mill and died in Bradford in 1973.

“I left Yorkshire in the 1950s and emigrated to Canada with my wife. It has been a good life here, but I visit England every year and Bradford every couple of years.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article