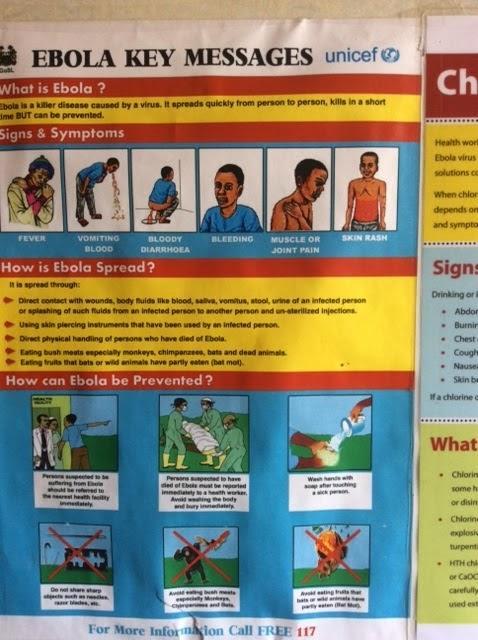

Another international health worker has been infected with Ebola, the third in the ten days since I have been here.

This time an American, flown out by one of the only two planes equipped with the very expensive isolation pods - $250,000 a flight.

WHO have been working on a standard approach to medevac and have agreed that all suspected cases will be sent immediately to the UK military facility co-located in Kerrytown, and then on to the most appropriate specialist medical centre.

There was a problem with the Cuban medic as the American planes couldn’t breach US embargo and land in Havana, so he has been taken to Geneva.

There is clearly a different price on international heads. The cases amongst Sierra Leonean health workers pass unnoticed whereas each international case sparks an anxious, rumour-driven chain of whispers.

Some cases are attributed to the type of personal protective equipment - the duck-bill masks becoming soaked in sweat until they cause a sense of drowning and panic - Ebola waterboarding. Other cases appear to be linked to the high-risk admission of patients through triage in Ebola centres, before they get to the sanctuary of the red zone.

Some infections appear to be transmitted in the community - casual encounters or patients calling to health care workers homes to seek help. The risks are small, but very real and the uncertainty about common cause is unsettling.

Last night as I was walking back from town to my guest house a young boy grabbed my hand. It was an affectionate gesture, a curious child. It was the first time anyone has touched me in nearly two weeks, and my immediate response was one of warmth, discovery of a long lost sense.

However a couple of seconds later and I was wracked with doubt. Who was the boy? Did his hand seem hot? I keep my hand out at a distance until I arrive home, and then I’m all Lady Macbeth with my alcohol gel and soap.

At the MSF headquarters in Bo an obstetrician tells me about the devastating impact of Ebola on maternity care. The bleeding related to this haemorrhagic disease has led to few pregnant women surviving, and almost none of the babies.

Worse still is the dismantling of routine antenatal healthcare: the loss of health care staff through Ebola; the fear of expectant mothers to go near an Ebola-infested health facility; a rise in pregnancy rates in high risk mothers from unplanned and teenage pregnancies.

Maternal mortality in the UK is 8.4 per 100,000 women. In Sierra Leone it has been recorded as nearly 5,000 per 100,000 and latest data suggests this has risen to 14,000 per 100,000 - almost 1 in every 7 pregnant women dying before delivery. The danger from Ebola pales in comparison.

Bo is at the heart of another viral haemorrhagic disease: Lassa fever. Over 5,000 people die every year from this one, but its spread is mainly through rats, and it’s less of a contagious risk to the world, geographically confined to this region in West Africa.

So like malaria, we can turn a blind eye to the death and suffering it causes, unless you happen to be living here. We are told to be on rat alert, keeping food and rubbish tightly sealed. Also to be careful of the rabid dogs. Rats for Lassa, dogs for rabies, mosquitoes for malaria, humans for Ebola - I’m living in a kind of apocalyptic inter-species World War III.

Meanwhile a rather sad string of Christmas tinsel has been hung up outside the town’s hotel. So the answer to Band Aid’s question is: yes.

MORE BLOG POSTS FROM PROFESSOR JOHN WRIGHT

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article