June 22, 1897, was an historic day in an historic year for Bradford.

That was the year Bradford received its royal charter, and Queen Victoria celebrated her Diamond Jubilee with a huge parade in London.

Richard James Appleton, a Bradford man known as ‘The First Knight of the Camera’ was there filming it – for public showing later that day in the city centre.

The entrepreneurial Appleton was taking part in a bold publicity stunt to promote The Daily Argus newspaper, which at the time was engaged in a circulation war with its rival, The Bradford Telegraph.

In the words of The Argus – quoted in the late Geoff Mellor’s seminal book Movie Makers And Picture Palaces: A Century of Cinema in Bradford 1896-1996: “To effect this ambitious scheme, 19th century photography, as represented by the noted Bradford firm of R J Appleton and Co, was summoned to the journalistic enterprise, and this combination of progressive forces achieved a veritable triumph of scientific research.

“The pomp and panoply of the State spectacle was recorded on innumerable negatives in every detail and, during the course of the evening, the process of development had been completed en route to Bradford, and a ‘Living Picture’ of the event was depicted to a concourse of people from the windows of the Argus offices.

“The State event took place on Tuesday, June 22, 1897, and Mr Appleton placed his cinematograph camera in a position where the State procession leaving St Paul’s could be photographed. The event recorded, he hurried to St Pancras Station where the Midland Railway had equipped a special coach as a dark-room. This was labelled Bradford Daily Argus Photo Laboratory.

“Throughout the journey to Bradford’s Forster Square Station, the laboratory technicians toiled in a light-tight and air-tight coach to develop thousands of animated photographic negatives. Difficulty was encountered in drying the results, but this was overcome.”

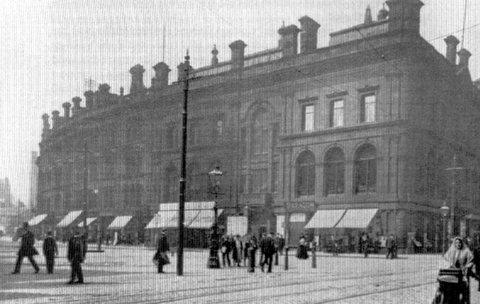

Appleton’s movie projector, the ‘Cieroscope’, had been demonstrated at Bradford Mechanics’ Institute in December the previous year. He set it up in a second-storey window of The Argus building. The pictures were projected on to a white screen erected across adjoining Watkins Alley.

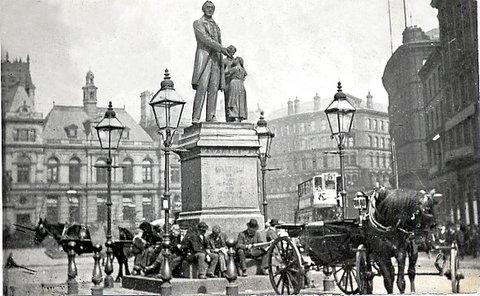

The display was repeated on three consecutive evenings, a small admission was charged with the proceeds going to the Mayor’s Jubilee Fund (Alderman John Sheldon). Then, on the Saturday, according to The Argus: “…the lights of Forster Square were temporarily extinguished and a large sheet faced the Square. At 11pm it was estimated that some 10,000 people had assembled in the Square to witness the screening of the historic Animated Pictures. When the programme was concluded, the National Anthem was played and the huge crowd dispersed in an orderly manner.”

Richard Appleton might have gone on to be a pioneering movie producer, but he became interested in the development of x-rays. In 1907 his retail photographic shop in Manningham Lane was taken over by George A Wilkinson, who moved it to smaller premises in North Parade.

However, Richard Appleton was not the first man on the planet to show moving pictures. Some say that honour belongs to the Lumiere brothers in France, others say it belongs to the eclectic American inventor Thomas Alva Edison.

But Geoff Mellor and Tony Earnshaw, artistic director of the Bradford International Film Festival and author of the book Made In Yorkshire, both attribute that pioneering breakthrough to Augustin Louis Le Prince, a Frenchman who married a Leeds woman. Earnshaw makes no bones about it: “Cinema was born in Yorkshire,” he says.

Le Prince, a maths and physics graduate, spent five years in New York from 1882. Upon his return in 1887 he completed his work on a single lens camera with which he made moving picture sequences at Roundhay Park and, in October, 1888, on Leeds Bridge – nearly eight years before Edison’s moving pictures were projected at Koster and Bial’s Music Hall, New York City, on April 23, 1896. Le Prince’s unexplained disappearance on September 16, 1890, after boarding a Paris-bound train in Dijon, would make an engrossing murder mystery.

As Mr Earnshaw says: “On the brink of unveiling one of the greatest inventions in the history of mankind, the creator of the world’s first single lens picture camera had disappeared from the face of the earth!”

Not entirely. His invention, together with his original 16-lens camera, can be seen in the National Media Museum.

Movie-making flourished in Bradford and other parts of Yorkshire from the 1890s until 1916, when the slaughter of young Yorkshiremen in Europe and the demands of the war economy virtually killed the embryonic film industry.

Film companies such as RAB Films (Riley and Bamforth), New Century Films, Hibbert’s Pictures, the Captain Kettle Film Company, Pyramid Films and The Imperial Film Company capitalised on the public’s appetite for moving pictures, whetted originally by fair owners as a way of attracting crowds.

These little films showed street scenes or people pouring out of factory gates.

Geoff Mellor unearthed a goldmine of archive material on the film companies that grew out of this fascination. Two of them, the Captain Kettle Film Company and Pyramid Films Ltd, shared the same building, a converted ice rink at Towers Hill on Manchester Road.

Henry Hibbert purchased it. In one half of the building he made his own films. From 1914 the other half of the premises was occupied by the Captain Kettle company. The name was based on the character created by the author C J Cutliffe Hyne. Films such as The Love Potion, The Mermaid (made on location at Morecambe) and The People Of The Rocks, the first Captain Kettle film, were produced.

Production ceased in 1915, the first full year of the First World War. The Scales Of Justice, reputedly the best of the Captain Kettle movies, was shot in Lister Park, Frizinghall and Bingley.

Pyramid Films Ltd took over the Captain Kettle studios and turned out feature films, newsreels and poular round-ups of local issues. In just one year, Pyramid Films managed to produce five films based on a new hero, Captain Jolly, a sequel to the intrepid Captain Kettle.

But the best of all its productions seems to have been a four-reeler called Maggie The Mill Girl, retitled My Yorkshire Lass: 6,000ft of “really good film”. Again, war put paid to Pyramid Films, just at the point where the film industry in Hollywood, Southern California, was taking off.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article