In April next year the University of Bradford’s ever-expanding campus will have a new addition, a £1.3m purpose-built centre dedicated to the teaching of science, technology, engineering and maths, or STEM for short.

Constructed of wood and located in the sustainable village quarter of the campus, this building will have laboratories and demonstration areas, a computer suite equipped with laptops, electrical and chemical equipment and something called a “beaming facility” for receiving and sending out, principally to schools, a variety of visual information.

This means that explanatory work and experiments can be conducted on site and beamed directly into schools.

To cut to the chase, this building is not intended to be an adornment to a gated grove of academia off Great Horton Road. Its purpose is to bring together university staff, schoolchildren and teachers and to inspire greater attainment in STEM subjects across the district.

With at least four staff, the building will have space to cope with 40 children at any one time, perhaps more if they are watching a demonstration.

Bradford’s STEM building is based on a version at London’s Imperial College. Other universities that specialise in chemistry have teaching facilities for schools on campus, but no other university has a purpose-built centre like this one, says Janet Smith Harrison, the project manager.

She said: “The building has been paid for by the Higher Education Funding Council. They gave us £3m to build a facility on campus, create a teaching programme for schools, and deliver a model that other universities can use.”

The shape and layout of the building, the design of its power and water supplies, evolved out of discussions with educationalists and students. In short, this is a bottom-up building rather than a top-down one.

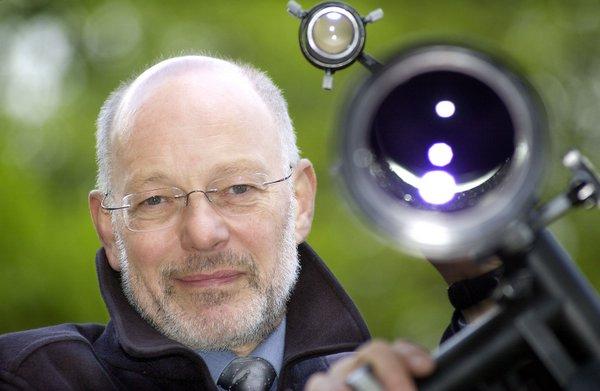

One of the university’s teachers involved in the building is Dr John Baruch, who created the Robotic Telescope programme for schools.

He said: “Some schools will want to come in and use the computing suite. They may want to go online and use the telescope for half a day. I think we would be working with secondary schools more than anything else, because primary schools are well endowed with computers.

“In many secondary schools they don’t have physics teachers. It’s very difficult for chemistry and biology teachers to fill in and do physics.

“We will bring them here and put them in front of physicists who are inspiring. Teachers will be able to ring up and talk to them.

“We want everybody to understand, we need a scientifically literate society. We want to work with businesses here and we want to work with overseas students whose parents may have connections with business in other countries.

“We see the university as a fulcrum to link in with the rest of the world, being innovative, creative and productive.”

Employers want more scientific literacy, so does the Government. Education Secretary Michael Gove has already signalled what he expects, with more rigorous A-levels and perhaps a form of Baccalaureate beyond that. Whatever happens, schools will still have targets to meet, so there has to be congruence between what schools need and what the university can offer.

Janet emphasises the importance of working in partnership with schools, a principle already operating between groups of schools. That is what this building has been designed for.

All this sounds exciting and a morale boost for Bradford as a whole. But the reality of youngsters’ expectations is apt to be demoralising, as the directors of hi-tech firm Pace found out in the 1990s. Young men they interviewed for jobs at their factory in Salts Mill were mainly interested in when they would get their first Maserati.

Dr Baruch acknowledges that this could be problematic.

With student loans and bank overdrafts to pay back, knowing that science is going to pay is a greater priority for many than whether it is going to be intrinsically compelling.

“If you give children a reasonably wide view of things they will want to be innovative. If you give them a narrow view they’ll just go for the X Factor and the Maserati.

“The challenge is to show them there’s a wider world and being innovative is rich in itself,” he added. It’s more than thinking outside the box, it’s designing the box in the first place.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here