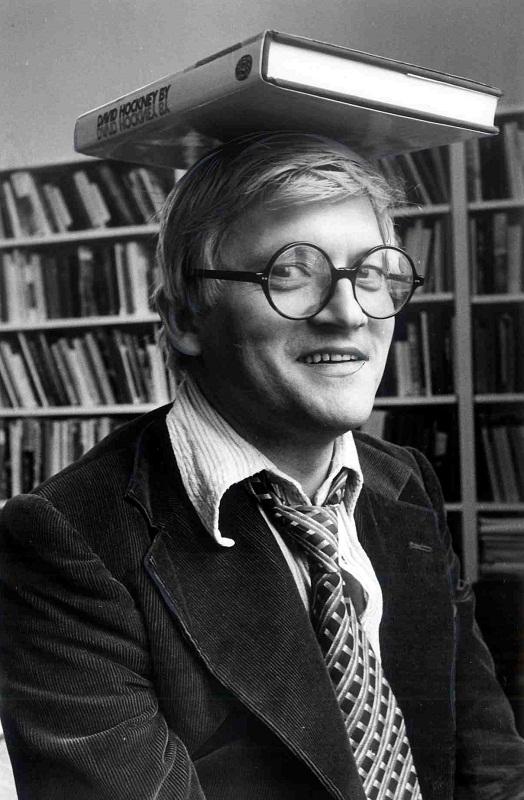

David Hockney, 75 today, said: “I thought I might try and ignore my birthday this year, I certainly don’t feel 75.”

That is why the Bradford-born artist is spending his birthday in the German spa town of Baden Baden, “for a week’s rest in the magic waters. I am quite exhausted and my assistants say I need it,” he added.

He has always worked conscientiously. During the four years he was learning his craft at Bradford Art College from 1953 to 1957, he frequently spent 12 hours a day drawing and painting.

For his Bigger Picture exhibition in all 12 rooms of London’s Royal Academy this year, he had a scale model of the building in his Bridlington studio, with miniature models of the vast paintings he intended to exhibit.

Similarly, he did this for all of the opera sets he designed for the Royal Court, Glyndebourne, La Scala and the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. Scale models of sets for Le Rossignol, The Magic Flute and A Rake’s Progress – his first international stage success – used to be exhibited at Salts Mill, of which he has become the secular equivalent of a patron saint.

A member of the Order of Merit, Companion of Honour, Royal Academician and Freeman of the City of Bradford: the honours he has accumulated over half a century, since winning the Royal College of Art’s gold medal for painting in 1962, are a testimony to his work ethic.

Bradford’s civic motto Labor Omnia Vincit – work conquers everything – could be his personal philosophy.

Those who associate Hockney only with the pleasure principle of Swinging London of the late 1960s (he says it didn’t swing for him, it was too conservative) or the suntanned glamour of Los Angeles swimming pools, may not know that for him work has always been a healthy stimulus.

As he said to me recently: “I don’t trust doctors much any more. Monet was a chain-smoker, you never see a picture of old Monet without a fag in his mouth. He began the nympheas paintings (water lilies) in his 70s, they took ten years, he died at 86, probably with a fag in his mouth.

“What he had was a terrific sense of purpose, something big to do, not measurable in medical terms at all, but I believe to be a powerful force, and you don’t have to have the genius of Monet to have it (but it helps), but no doctor will tell you this... I get on with my work. I’ve a lot to do. I’m continuing with the ‘experiments’...”

The paintings, pictures and books he has made have earned him a fortune, enough to employ a dozen or more people here and in the United States and to maintain extensive houses and studios in LA, London and Bridlington. He uses his economic power to try new things, to nudge boundaries.

“Using 18 cameras we filmed 12 jugglers, all juggling at once. Try that with one camera and get 12 in the picture, you’d have to be too far back... It makes the ordinary TV picture look primitive... I’m very proud of our nine-minute film. I think it takes us into new territory.”

At the Royal College of Art he was told he was “mad” for writing words on his pictures. Probably, his detractors didn’t understand – he may not have understood himself – that he was looking for something new.

His exhaustive experiments with Polaroid cameras, fax machines, laser printers, digital cameras, video cameras, computer technology, iPhone and iPads, embody his desire to explore new territory.

He has designed a postage stamp for the Royal Mail and the front cover of the Bradford telephone book for BT. In 1984 the Bounce for Bradford he did for the T&A reportedly sold 10,000 copies for 5p or 10p a time at the Royal Academy’s summer exhibition. The following year he designed and completed a large photographic montage of what is now the National Media Museum.

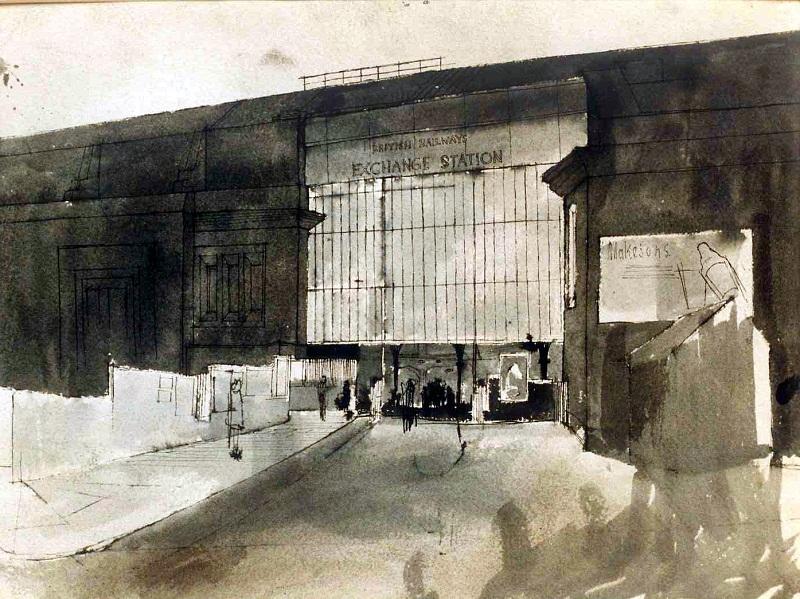

In his youth, Hockney left the family home at Hutton Terrace, Eccleshill, to push his pram of paints and brushes about Bradford, capturing on bits of hardboard the landscape of his hometown. A good deal of it was about to disappear – Exchange Station, for example.

“Leeds was never as daft as Bradford in keeping a great deal of the Victorian city, and benefits from it now. The media was never critical enough and was far too close to the weak and cowardly politicians.

“It is a very sad country now, far too much self-hatred which I do not share. It will be a big crime to pull that building down (he means the Odeon), and I will say so. The city of my childhood does not exist at all, there were no ghettos then and why there are requires an honest explanation.”

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Hockney’s brother Paul (Lord Mayor of Bradford in 1977) used to put up ‘Bradford – A Surprising Place’ posters in Los Angeles. Unlike some Bradfordians who tell strangers they are from Yorkshire, Hockney has always made a point of telling people he is from Bradford.

In Jack Hazan’s 1974 feature film A Bigger Splash, Hockney regales one of his New York friends with stories about family life in Eccleshill in the 50s, how his father, Kenneth, used to wheel an easy chair to the local telephone box if he was expecting a call.

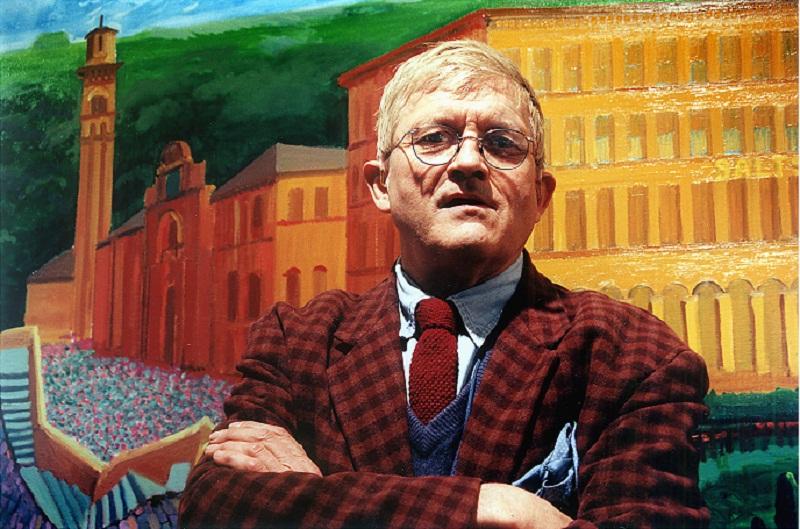

When Salts Mill owner Jonathan Silver was dying of cancer in the summer of 1997, Hockney tried to ease his friend’s pain by acceding to his most earnest request that he would paint the Yorkshire landscape. Among the pictures he did was the one of the Yorkshire sandstone building, bright as a bar of gold.

Last week he was entertaining visitors from his old school, Bradford Grammar, and noting the punitive fines imposed on pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline for marketing the anti-depressant Paxil to patients under 18.

“In the coming turmoil I will have the calming tobacco, everybody else will be on pills,” he said. Recently he has taken up smoking a pipe again because, he said, the tobacco was superior in quality and flavour.

“...not words you can use about our dreary age...I am just going out to draw on Woldgate, a better and bigger view of the world,” he added.

e-mail: jim.greenhalf@telegraphandargus.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel