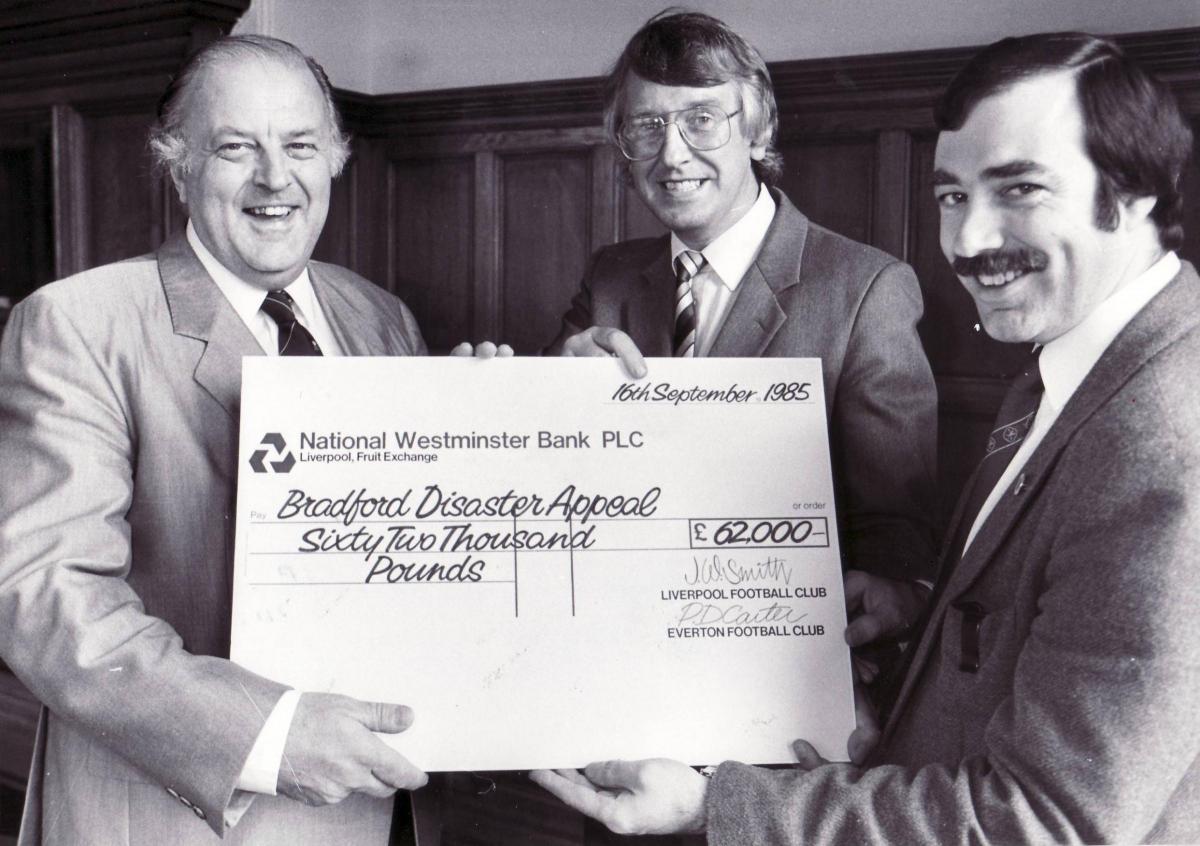

WHEN the Bradford City Fire Disaster Fund was wound up in the autumn of 1986, £4.25m had been paid out to 400 people.

Two of the many people who did invaluable work behind the scenes to ensure its success were Bradford lawyer Roger Suddards and Bradford Council chief executive Gordon Moore.

Mr Moore, a civil servant in Bradford for 21 years until his retirement in 1986, ensured that City Hall was opened on the Sunday. He assigned Council staff to coordinate fund-raising efforts, visit the hospitals and operate a helpline.

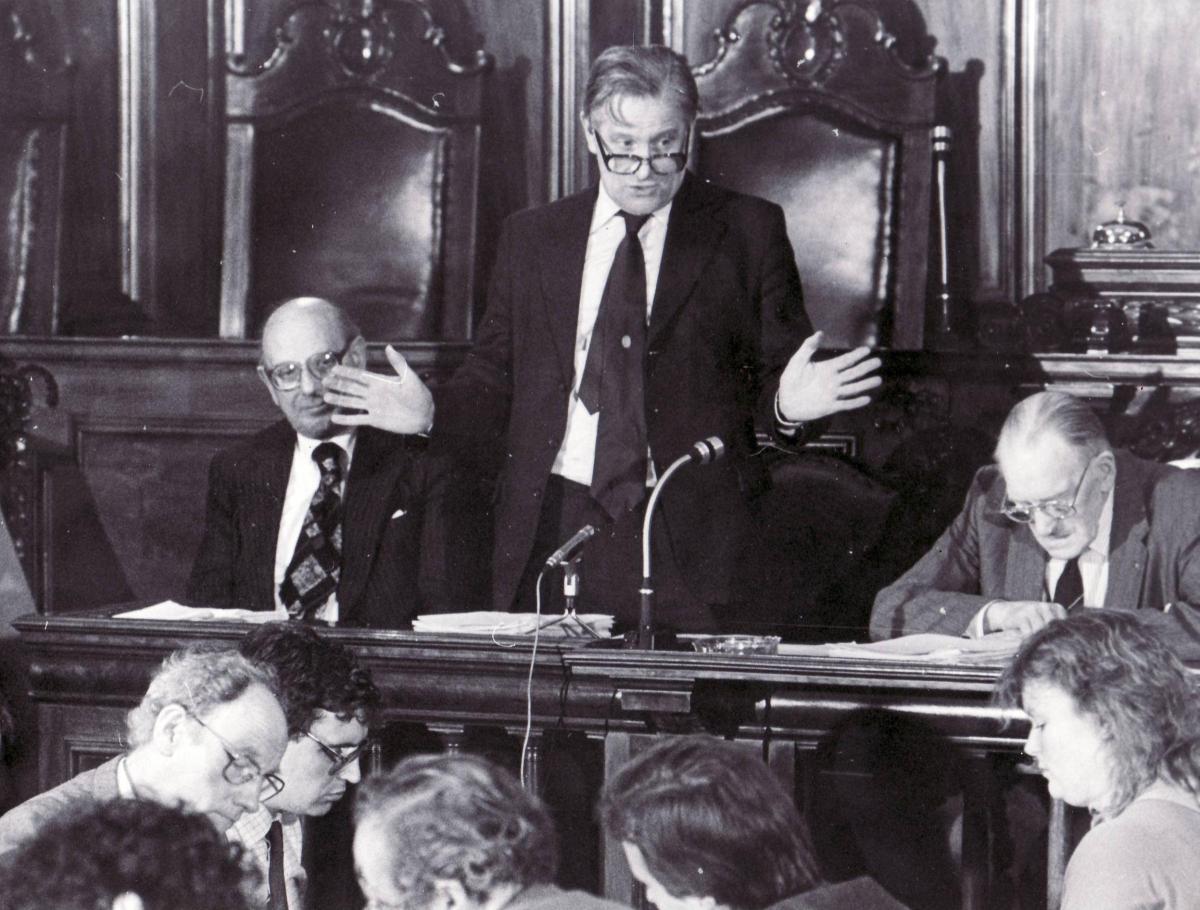

Although an ebullient and commanding figure, Mr Moore knew how to pick the right people for the job and then let them get on with it. He encouraged officers to use their initiative.

Bradford born and bred, Roger Suddards CBE, a writer of books about the law, architecture and Saltaire, and who became one of only 11 English Heritage Commissioners, seemed the natural man to mastermind the legal status of the disaster fund.

MORE BRADFORD CITY FIRE ANNIVERSARY HEADLINES

The most problematic aspect of it was the best way of distributing money to the families of the bereaved and those who had suffered injury.

He met the appeal organisers of the Penlee and Aberfan disaster funds to help him decide how to avoid the kind of controversy that had marked the Penlee appeal.

In 1966, the collapse of a slag heap in the Welsh village of Aberfan killed 144 people including 116 children. In 1981, the Cornish lifeboat Solomon Browne and all eight crew were lost at sea.

The trust fund Mr Suddards set up with Gerald Hodges, Bradford Council's finance director, and Keith Marsden, chairman of Pennine Radio, ran on oiled wheels. Four people visited the injured and bereaved and a panel of three assessors weighed up the information.

Gerald Hodges, now 90, said two types of trust fund were considered: a standard charitable trust and a discretionary charitable trust.

"The advantage of a standard charitable trust was that any investment received was tax free. The disadvantage was that Charity Commission rules and regulations had to be abided by," he said.

"The disadvantage of a discretionary charitable trust was that income tax was paid on interest accumulated by donations. The advantage was that trustees had complete discretion in the management of the fund."

A discretionary charitable trust, it was agreed, was the better choice for Bradford. Also, the trustees agreed that lump sum payments should be made quickly rather than smaller amounts over a long period. Sums paid out were not to be publicised.

By Wednesday, May 15, a document had been drawn up for signing by the three trustees at a press conference. Less than a week after the fire the Disaster Appeal trust fund was in business. By the end of the week donations and pledges topped £500,000.

Eight times more than that poured in rapidly. Within ten months Mr Hodges said 95 per cent of the £4.25m total was paid out.

Mr Suddards said at the time: "The feedback we've had from those who received money showed how enormously they appreciated having it at a time when they needed it most."

The cost of administering the fund was kept at one per cent of the total. The three trustees were not paid.

As a result of Mr Suddards's work he was asked to Downing Street to talk to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher about his idea of creating multi-skilled emergency units to deal with disasters by land, sea and air.

Mr Suddards died at the age of 65 in 1995. Mr Moore was 69 when he died in 1996. The Disaster Appeal remains their legacy and their memorial. Bradford has no other.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here