TO Anne Fletcher, the story of her great great great uncle - a Bradford mill worker who broke the bank of Monte Carlo - was just an amusing tale passed down through the family.

How, in 1880, could a man who had worked in mills since childhood and never even left the North of England make his way to Monaco, playground of the super rich, and win a fortune?

But when she started to research her Victorian ancestor, Joseph Hobson Jagger, Anne discovered that he did, indeed, travel from Bradford to the Casino de Monte Carlo, where he won the equivalent of £7.5 million. And Anne believes it was Joseph’s skills acquired in Bradford mills that led him to identify a flaw in the roulette wheel, enabling him to work out which numbers came up most often.

“I grew up with the story and was fascinated, but thought it was just something passed down in the family,” says Anne. “My dad wrote about it in an article in the Telegraph & Argus back in 1960. When he died, I embarked on the research to fill in the gaps, as a tribute to him.”

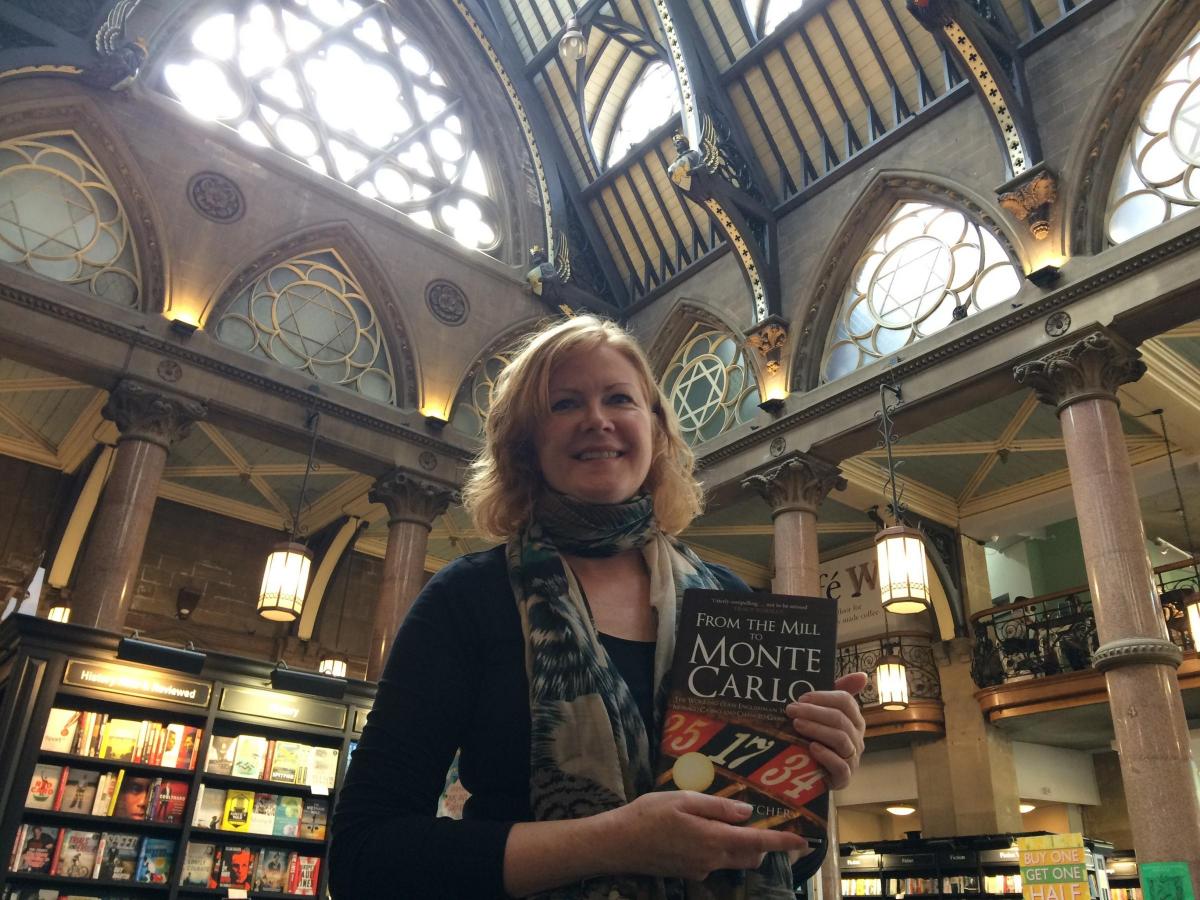

In her book From The Mill To Monaco, Anne tells Joseph’s story, revealing what led a seemingly ordinary man to travel to the south of France at a time when most people lived and died within a few miles of where they were born.

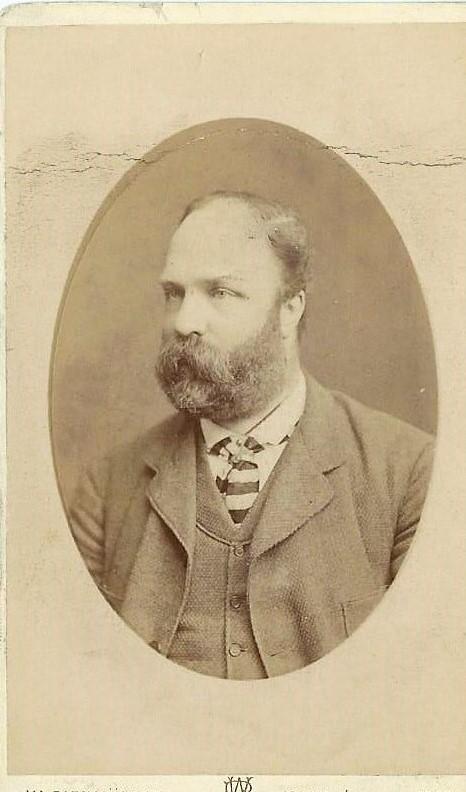

All Anne had to go initially on was a key, a photograph of Joseph, her father’s T&A article and Fred Gilbert’s music hall song The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo running through her head. Her research took her from the archives of Bradford’s Local Studies Centre and the streets where Joseph lived, to Monte Carlo’s historic casino where he made his fortune.

It was a far cry from debtors’ prison Joseph was facing. The idea was that you worked off your debt, and incarceration costs, through hard labour. But the system was often corrupt and everyone knew that once in, you were unlikely to come out. Conditions were brutal, with families often living in cramped, cold cells. It wasn’t uncommon to die from exposure or starvation. When Joseph went bankrupt, he and his family (his youngest child was just two) would have ended up in debtors’ prison had he not decided on a desperate gamble...

“No-one in the family really knew why he went to Monte Carlo, but my research showed he’d gone bankrupt,” says Anne, who traced her family history back to early 1700s Bradford and discovered that Joseph was the seventh generation to live and work here. “He worked his way up and ran a little business finishing fabrics, but fell on hard times. He was part of the Victorian working-class who were utterly lost. He was desperate - so he came up with a crazy scheme.”

Adds Anne: “Newspapers at the time covered Monte Carlo, it’s a place he’d have heard of. He borrowed some money from family and went there with his eldest son, Alfred. With gambling frowned upon in Victorian society, and Joseph a Methodist, he kept his plan quiet. He caught a train to London, then to the coast, a steam ship across the Channel, a train to Paris and another to Monte Carlo. Railways were relatively new and dangerous. He didn’t speak any French. It was an extraordinary journey to take.”

Joseph had never been a gambler, but through his engineering nous, picked up in Bradford’s textile mills, he worked out how a slight bias in the roulette wheel meant balls were more likely to land on certain numbers. Observing tables, he placed his bets. “He worked out a technical flaw that enabled him to play, and win, legally,” says Anne, a historian and writer. “We’re not sure how long he spent at the casino. The story passed down said a week but I think it was longer. There was surveillance at the casino but because Joseph’s system wasn’t a usual one he didn’t get spotted at first.

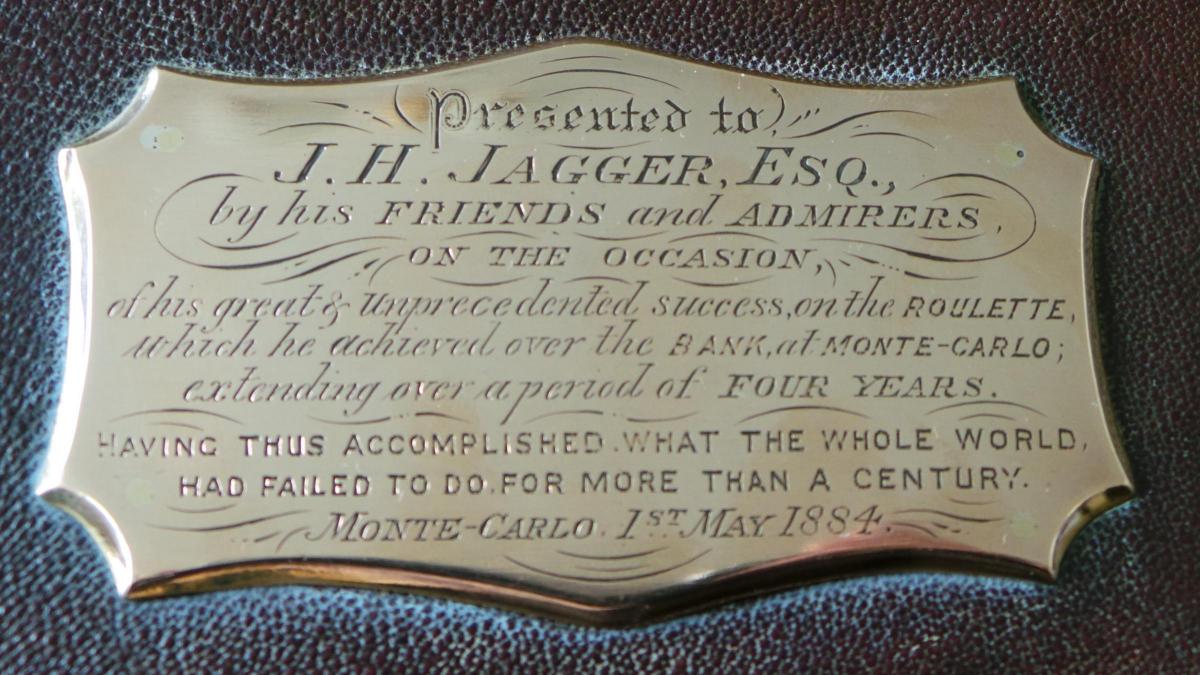

“He was the first person to break the bank legally. And, unlike other players, he knew when to stop. He was a canny Yorkshireman who went there for a reason.”

Joseph won £80,000 - over £7m in today’s money - and returned to Bradford, where he bought 30 terraced houses in Great Horton for family and friends. “He could’ve bought himself a big fancy house, but he lived at Greaves Street where he died in 1892, aged 63,” says Anne. “He was part of the community, he wanted to be with his family and friends.” Roulette tables we re-designed after Joseph’s win; leaving his legacy in casinos worldwide. Anne played roulette in the room where Joseph had his win. “It was fascinating but terrifying, there’s a lot of money thrown around there,” she smiles.

Researching Joseph’s story brought her closer to her Bradford roots. “My parents were from Bradford but I’ve never lived in Yorkshire. Now I’ve met branches of the family I didn’t know, some are still in Bradford. There’s a sense of relief in the family that Joseph’s story is true. Little was known about it because the casino would have hushed it up - it was bad PR - and with him being so modest.”

It would make a terrific film. Who would Anne want to play Joseph? “Sam West would be perfect,” she says. “His father, Timothy West, was born in Bradford so it would be very fitting.”

* From the Mill to Monte Carlo, published by Amberley, £20.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel