IT has been added to the Collins Dictionary and is frequently entered into search engines - and now ‘Fake News’ is on display at the National Science and Media Museum.

Propaganda, alternative facts, doctored images, and unverified statistics can be found throughout the history of human communications, but do contemporary motivations and modes of dissemination make this apparent spike in reported misinformation a particularly 21st century phenomenon?

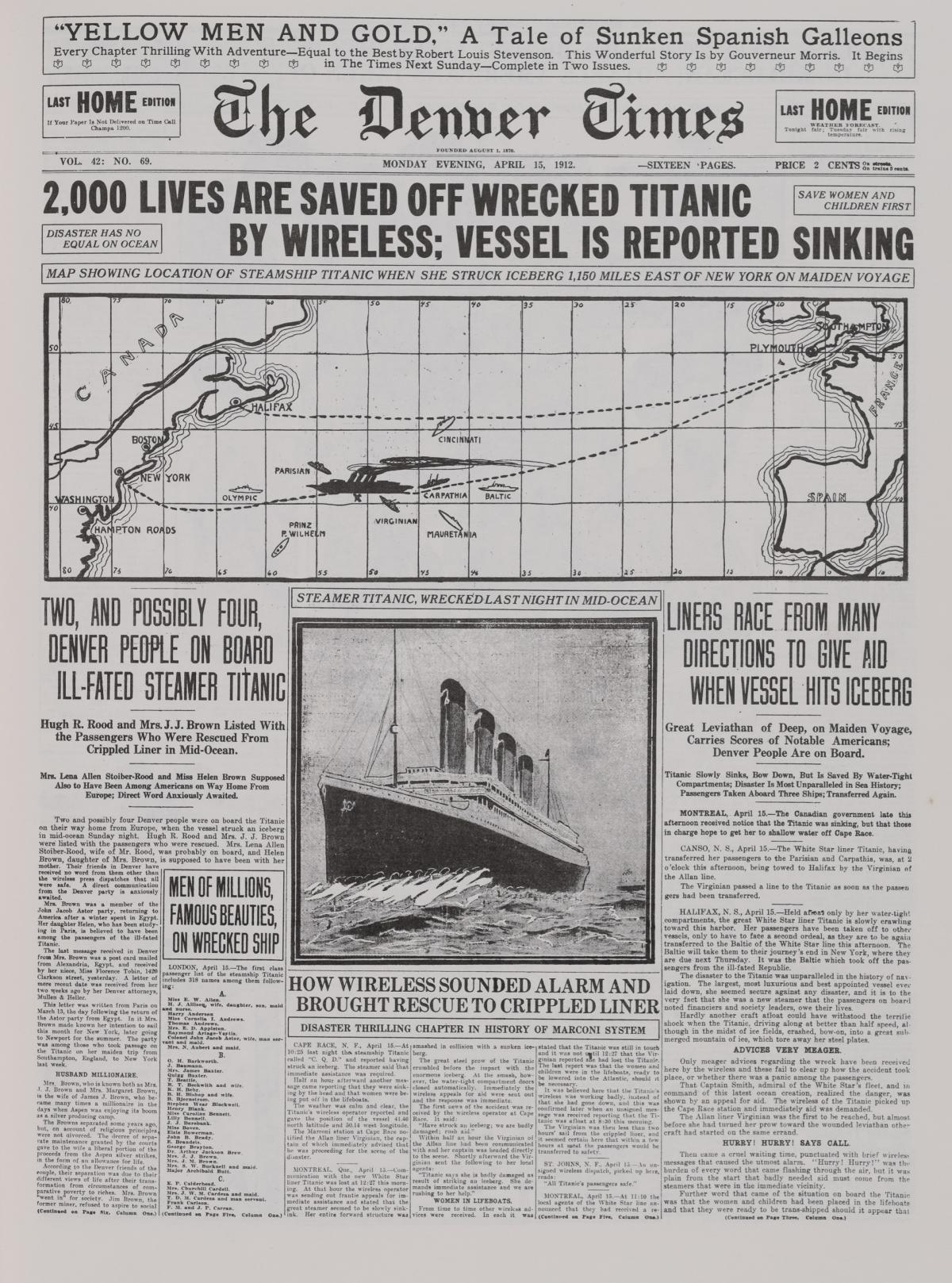

The Fake News exhibition examines historic examples from the National Science and Media Museum’s own collection and archives, alongside contemporary news and social media outlets. It looks at recent media controversies, such as the disputed crowd attendance at Donald Trump’s presidential inauguration, historic material including the Cottingley Fairies hoax and inaccurate news reports from the Titanic disaster. It also looks at viral stories from the internet which demonstrate how far and fast information, claims and counter claims now travel before ‘the truth’ catches up.

Fake News asks: How did the famous Cottingley Fairies photographs become known globally before the digital age? Did newspaper readers really believe reports in 1835 of bat creatures living on the moon? For how long did people think the Titanic had survived hitting an iceberg following mistaken news reporting?

John O’Shea, senior exhibitions manager at the National Science and Media Museum said: “The way we use technology today to consume and share current events has transformed beyond recognition in the last decade.Through our collections and working with partners, this exhibition tries to stand-back from the noise to see if we really are breaking new ground when it comes to fake news.”

The exhibition identifies five factors which can contribute to fake news: political gain; misreporting; going viral; financial gain; and ‘not letting the truth get in the way of a good story’.

* As a political tool: Sean Spicer, the first White House press secretary of President Donald Trump’s tenure, told reporters that the crowd at Trump’s inauguration ceremony was ‘the largest ever’. This claim came under scrutiny around the world when photographs of the Trump event and Barack Obama’s in 2009 were placed side by side.

* Going viral: This year marks the 100th anniversary of one of the world’s biggest public hoaxes - the Cottingley Fairies photographs. In August, 1917 cousins Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths took a camera, now part of the museum collection, to Cottingley Beck, later claiming they had taken photographs of fairies. What appeared to be staged images to some were taken to be genuine by others. When the photographs came to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s attention, they were scrutinised by scientists and academics, and the girls were encouraged to take more photographs. It wasn’t until more than 60 years later that the cousins owned up to faking the images.

* Don’t let the truth get in the way…In 2017 the British press ran a story with photos and video footage showing Leader of the Opposition Jeremy Corbyn failing to bow his head to the Queen at the state opening of Parliament. Criticism of this apparently disrespectful act was followed by discussions of the correct protocol.

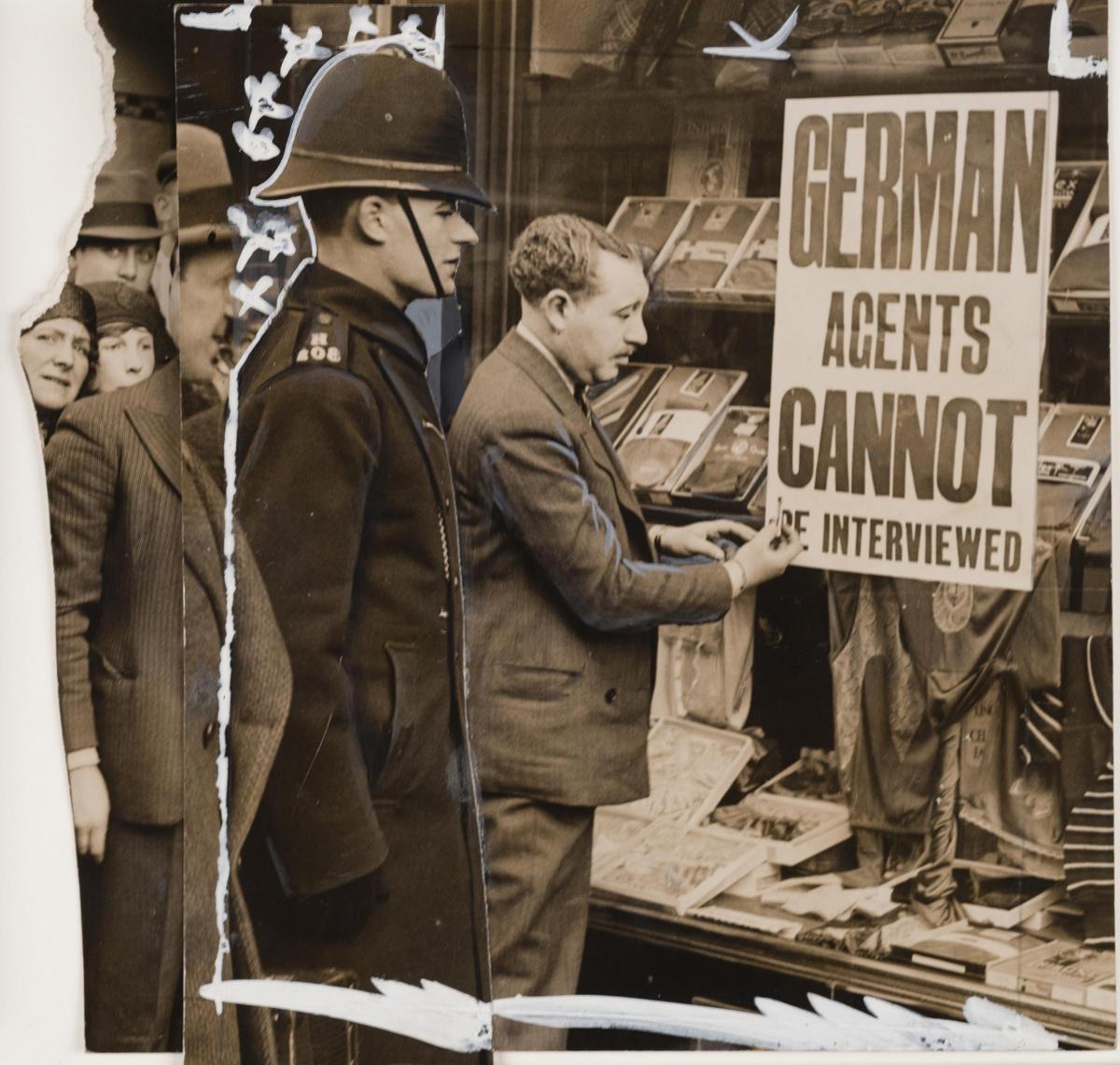

Photographs from the Daily Herald picture library include examples of images apparently altered to back up a story angle. Archive papers from the University of Bradford’s Peace Studies department show that unverified telegrams stating that all passengers from the Titanic had been rescued were reported as fact in newspapers, before the full tragedy came to light.

For profit: In 2016, Veles, a town in Macedonia, became the home of more than 100 pro-Trump websites publishing plagiarised news about the US elections. By sharing links with Facebook groups, the websites attracted thousands of clicks, generating advertising revenue for the owners. And in 1835 the New York-based Sun newspaper reportedly increased its circulation with articles claiming that astronomer Sir John Herschel had discovered ‘bat creatures’ on the moon.

* Fake News runs at the National Science and Media Museum, November 24 to January 28, 2018. Visit scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here