HE late Mark Keighley spent his working life steeped in Bradford’s two major industries - wool textiles and engineering.

After several years editing the company newspaper of Hepworth & Grandage, one of the city’s “Big Three” engineering firms, he joined the Wool Record in 1962.

Based in Bradford, the wool-textile magazine had a global circulation, and during the many years he wrote for and later edited the publication, Mr Keighley became an authority on all aspects of the industry.

Here we publish the latest extract from Mr Keighley’s memoirs, The Golden Afternoon Fading, a remarkable look back at the industrial, business and social life of Bradford as its industrial golden days began to pass into history.

“The Parkland Manufacturing Company, of Greengates, a group owning 20 mills and employing 2,000 people, were now the largest producers of men’s worsted suitings in the world.

In 1955 they had been the first in the British worsted industry to invest in the revolutionary Swiss-made Sulzer projectile weaving machines that were twice as fast as conventional looms and offered manufacturers - “Quite extraordinary production possibilities”, said the president of the Bradford Textile Society, Mr. DWM Scott.

The outstanding feature of the Sulzer machine was its unique system of weft insertion. A steel gripper projectile only 9cms long and 40gms in weight replaced the much larger and heavier traditional wooden shuttle. Unlike the wooden shuttle, it no longer carried the weft thread reserve with it when it made its flight through the “shed” (the gap between warp and weft through which the shuttle travels) but drew it from stationary cross-wound packages and then inserted it at high speeds in the cloth that was being woven.

Years later, Jack Hanson, Parkland’s chairman, disclosed that to enable them to “start with a completely open mind on an unconventional machine” the company had in 1955 engaged Derek Land, a qualified engineer, “who did not know warp from weft” to take complete charge of the pilot plant of 16 multi-colour Sulzer high-speed weaving machines they had acquired. “This unorthodox move proved completely successful,” Mr Hanson remarked.

The days of traditional British-made shuttle looms were numbered, but few people guessed that at the time. Admittedly, the new looms were expensive, and cost £3,000 each – far more than a Northrop loom or a Hattersley Standard. But by the early 1970s Parkland were operating more than 160 of the new Sulzer machines at their mills in Bradford, Huddersfield and Leeds. Progress always comes at a cost.

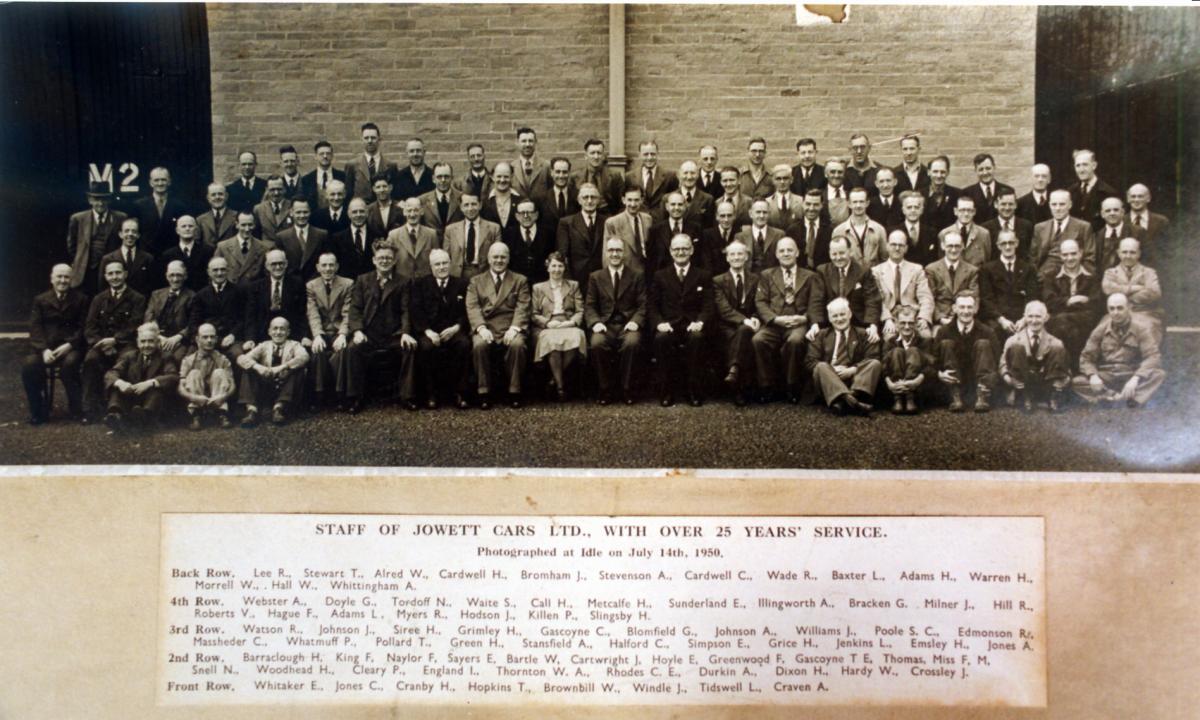

One of Bradford’s most famous companies, Jowett Motors, which made a range of motor cars and commercial vehicles at a factory in Idle, ceased production in the closing months of 1954 to everyone’s dismay. For some inexplicable reason many local people became convinced that Briggs Motor Bodies of Dagenham had refused to continue making and supplying the vehicle bodies that Jowett’s needed, and this had precipitated the closure, but that was far from the truth.

It was not until I read a copy of The Complete Jowett History edited by Paul Clark and Edmund Nankivell, and published in 1991, that I finally understood what had really happened. Chapter 10 of the book, sub-titled “The final throw of the dice”, and written by Mr Nankivell, is a brilliant and highly-detailed account of the complex chain of events.

In 1950, Mr Nankivell pointed out, the Jowett board had made a realistic but hard-hitting review of the range of products and reached the opinion that the iconic Javelin saloon was too noisy and unreliable, the Jupiter sports car was still “untried”, and the Bradford van was, amongst other things, too old-fashioned in appearance – although hundreds of modern-day Jowett enthusiasts would probably claim this is one of the vehicle’s most endearing points.

By 1952 the Javelin was facing competition from cars made by rival manufacturers and production had slumped to about 70 a week, a figure that fell to 50 within a matter of months. The company’s finances were sound, but every inch of spare space at the Idle complex was filled with unsold and unbuilt Javelins and a large number of Bradford vans awaiting a buyer. The situation was serious and Jowett’s asked Barclays Bank to extend their overdraft, and Briggs Motor Bodies to revise their credit terms.

To cut a long story short, Jowett’s asked Briggs to halt further deliveries of car bodies and to scale back existing production. Jowett’s plan (Mr Nankivell revealed) was to continue making Javelins from the stockpile of bodies that had accumulated on their Idle premises, to pay off their debts, and to enter into a new arrangement with suppliers such as Briggs.

Briggs, to their everlasting credit, and at considerable inconvenience and expense to themselves, took steps to help Jowett’s to stage a recovery by modifying existing financial and repayment agreements, and Barclays granted Jowett’s the extension to their overdraft.

Prospects looked brighter the following spring. The company had orders for 390 Javelins, 24 Bradford vans and 22 Jupiters - but it was all too little and far too late.

The company had recorded heavy trading losses and no dividend had been paid to ordinary shareholders. On February 18 1954 the company sold their Oak Mills plant at Clayton to the British Wool Marketing Board, and on October 25 of that year their Idle premises became the property of the International Harvester Company, who had earmarked them for the production of farm tractors.

“At least a large number of jobs were saved, but the Jowett Story had come to an end.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here