THE movie of The Black Panther was vilified on release in 1977. So what makes it any more acceptable now, almost 40 years later? Michael Black reports.

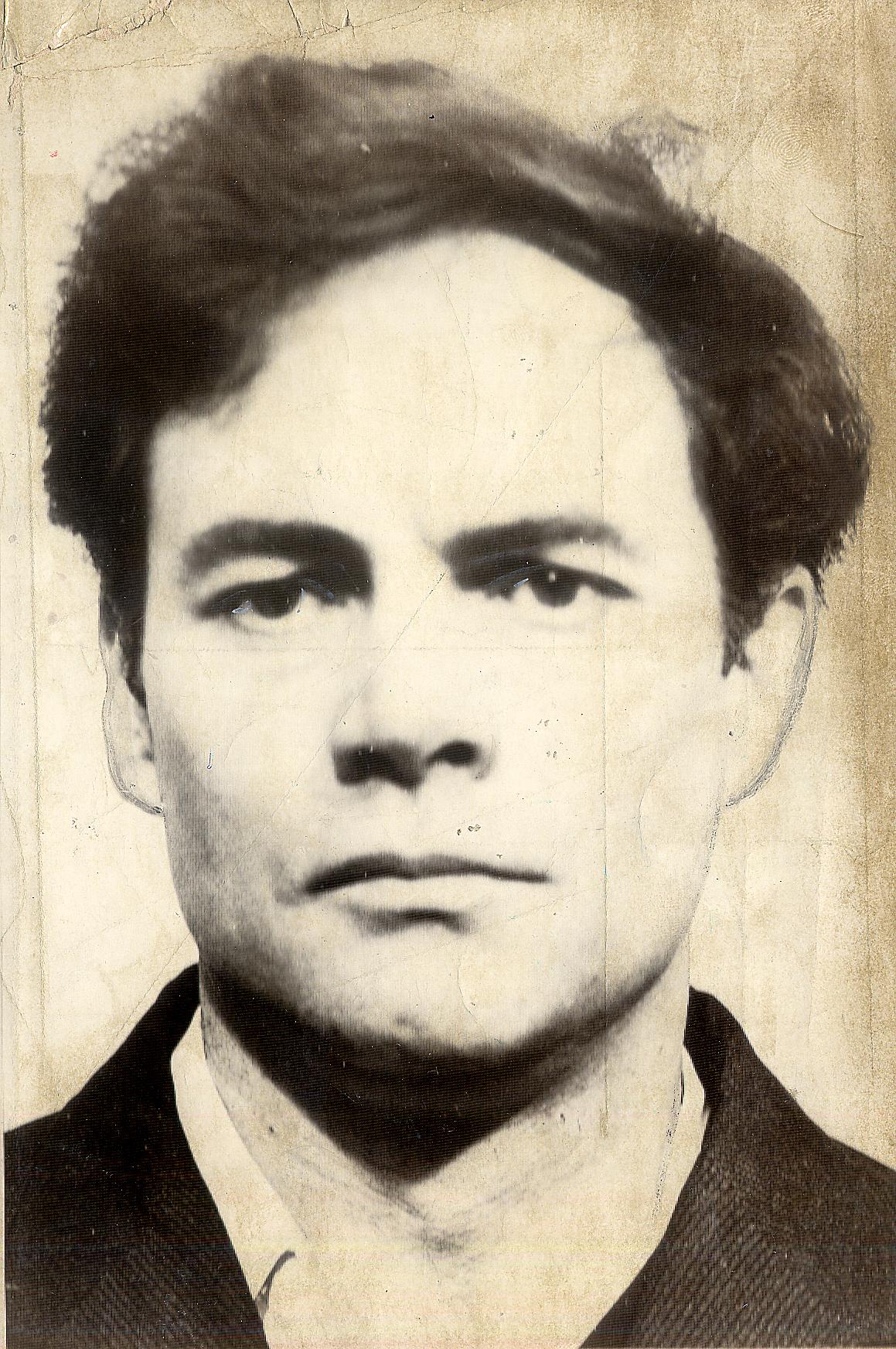

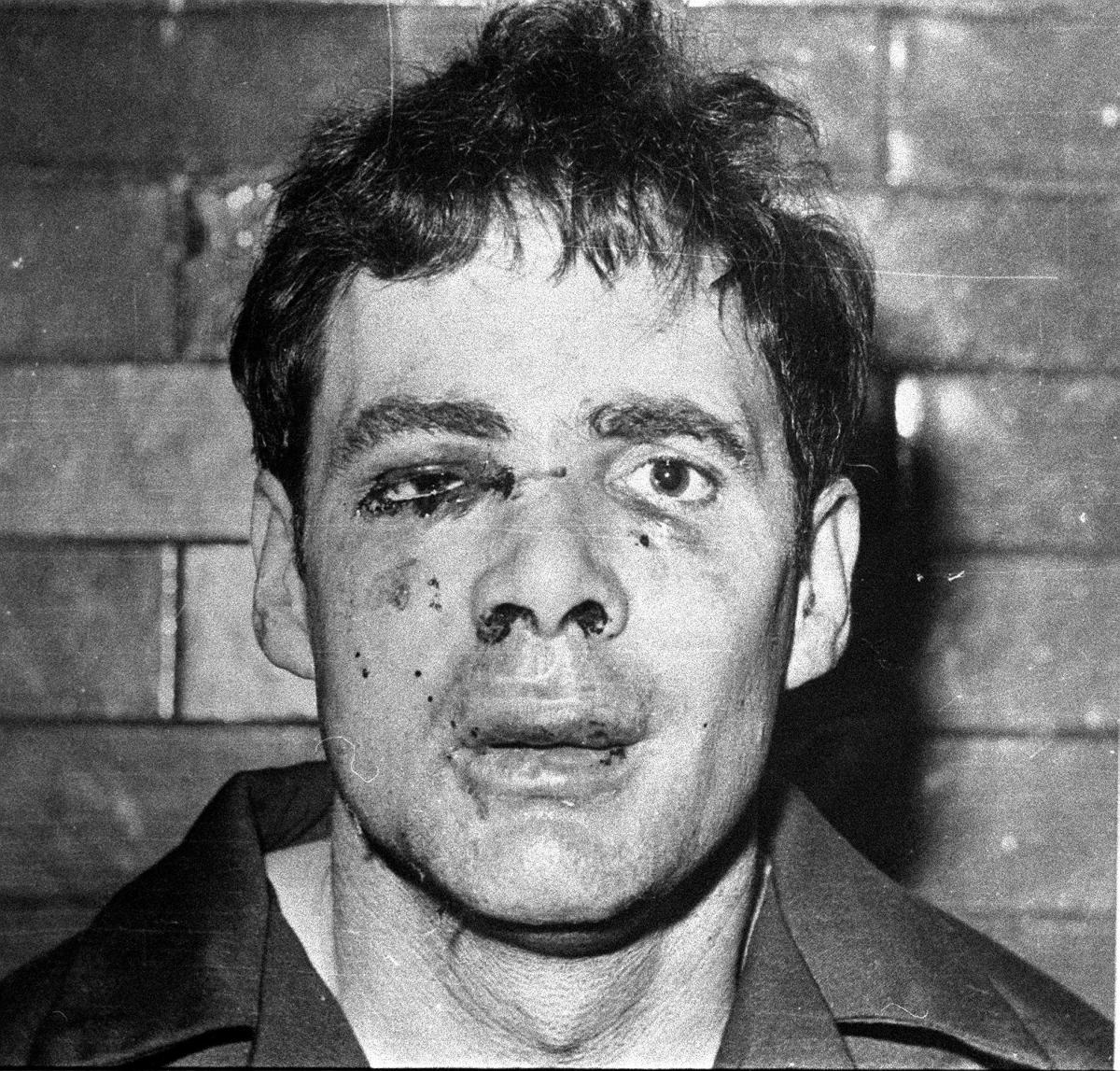

Summer, 1976. Donald Neilson, a Bradford builder and former taxi driver who had drifted into burglary that escalated to robbery, kidnap, blackmail and murder, was handed five life sentences following his trial at Oxford Crown Court.

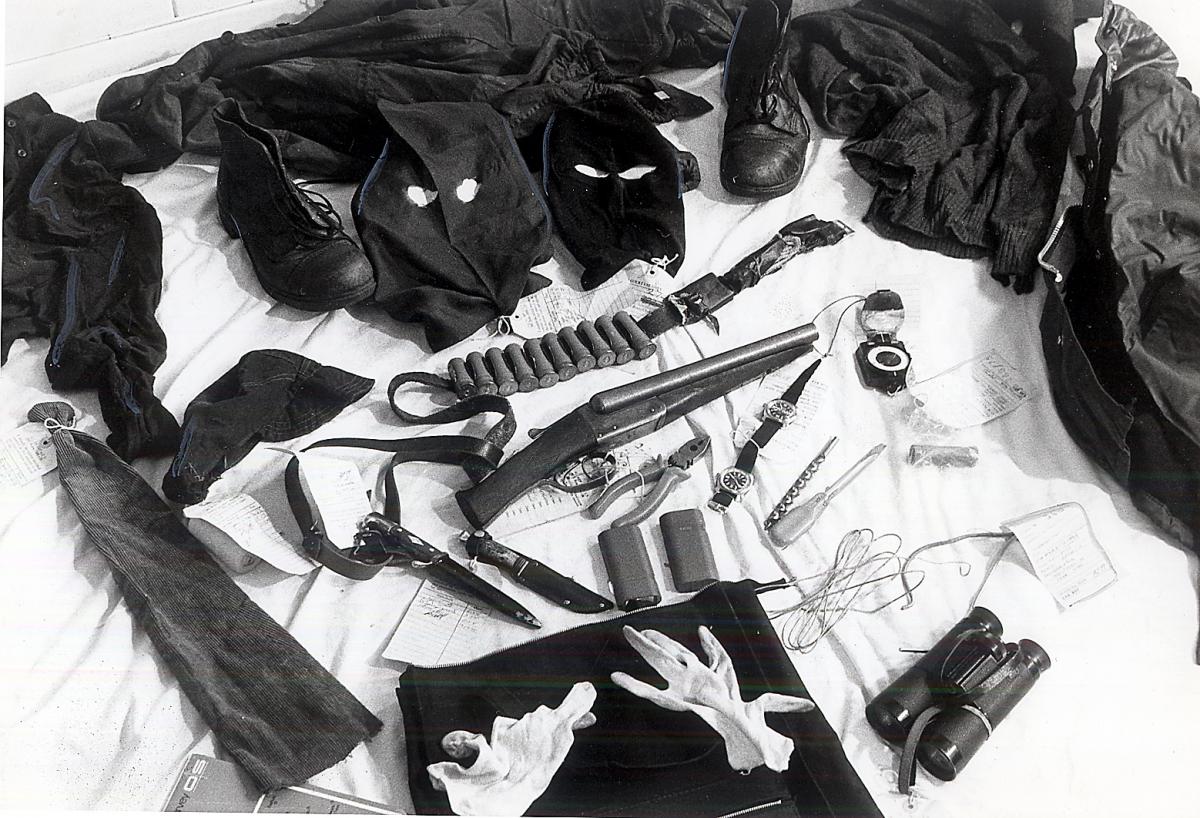

Neilson, dubbed the Black Panther, was the man who had carried out hundreds of burglaries. He later graduated to robbing sub-post offices.

In 1974 he shot and killed three men in cold blood and finally embarked on his grand money-making scheme: the kidnapping of teenage heiress Lesley Whittle, 17, only for the plan to backfire and lead to her lonely death in a drainage shaft.

The crimes of the Black Panther had gripped the nation. And especially in Yorkshire, in which another killer was on the loose.

By 1976 the Black Panther was under lock and key. And there the saga should have ended, with 39-year-old Neilson cast into the British penal system and consigned to history.

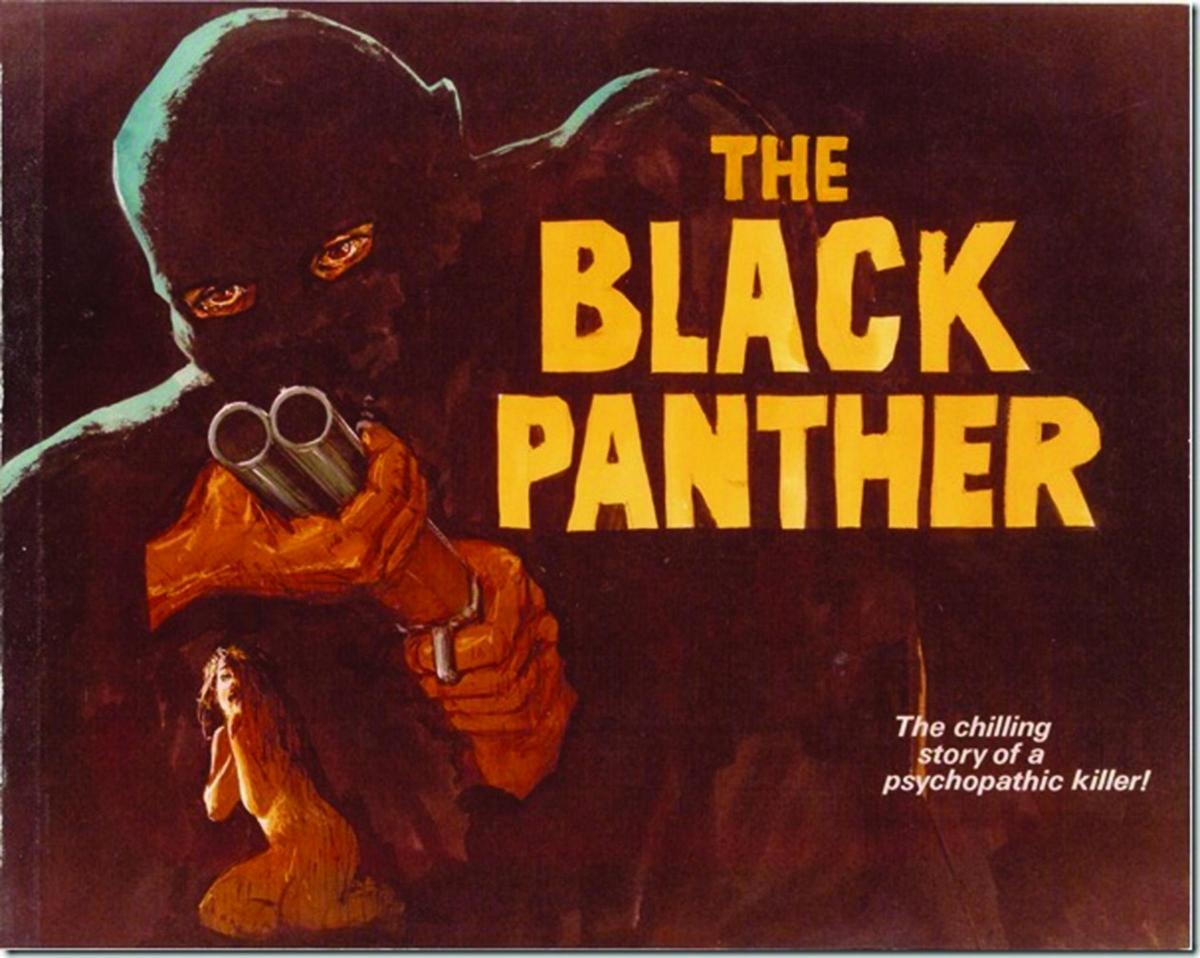

Yet little more than a year later controversy erupted over the release of a low-budget British movie based on his life and crimes. Neilson may have been jailed but The Black Panther brought his crimes vividly to back into the public eye.

The reaction was swift and wholly negative with police, the public and the Press joining to condemn a project considered salacious, offensive and exploitative.

The film was to get a release late in 1977, with test screenings at six sites. But three were cancelled due to bad weather and others were shelved due to pressure from local authorities, which considered the film to be in bad taste.

And so The Black Panther faded from cinema screens. It would later enjoy a second life on video in the 1980s, but even then some viewers damned it as a ‘video nasty’.

Autumn, 2015. The Black Panther has emerged on DVD, re-released by the august British Film Institute. The BFI says it “is proud to be bringing this forgotten entry from the history of British cinema back into circulation for a new generation of viewers to discover and appreciate.”

Sam Dunn, head of video publishing, who describes the film as “over-looked and under-appreciated”, highlights what he calls its “direct, un-sensational approach to its harrowing subject matter” which, he argues, makes it “chilling, yet non-exploitative”.

So was there a rush to judgement? And was there a move by the Establishment to scupper the film?

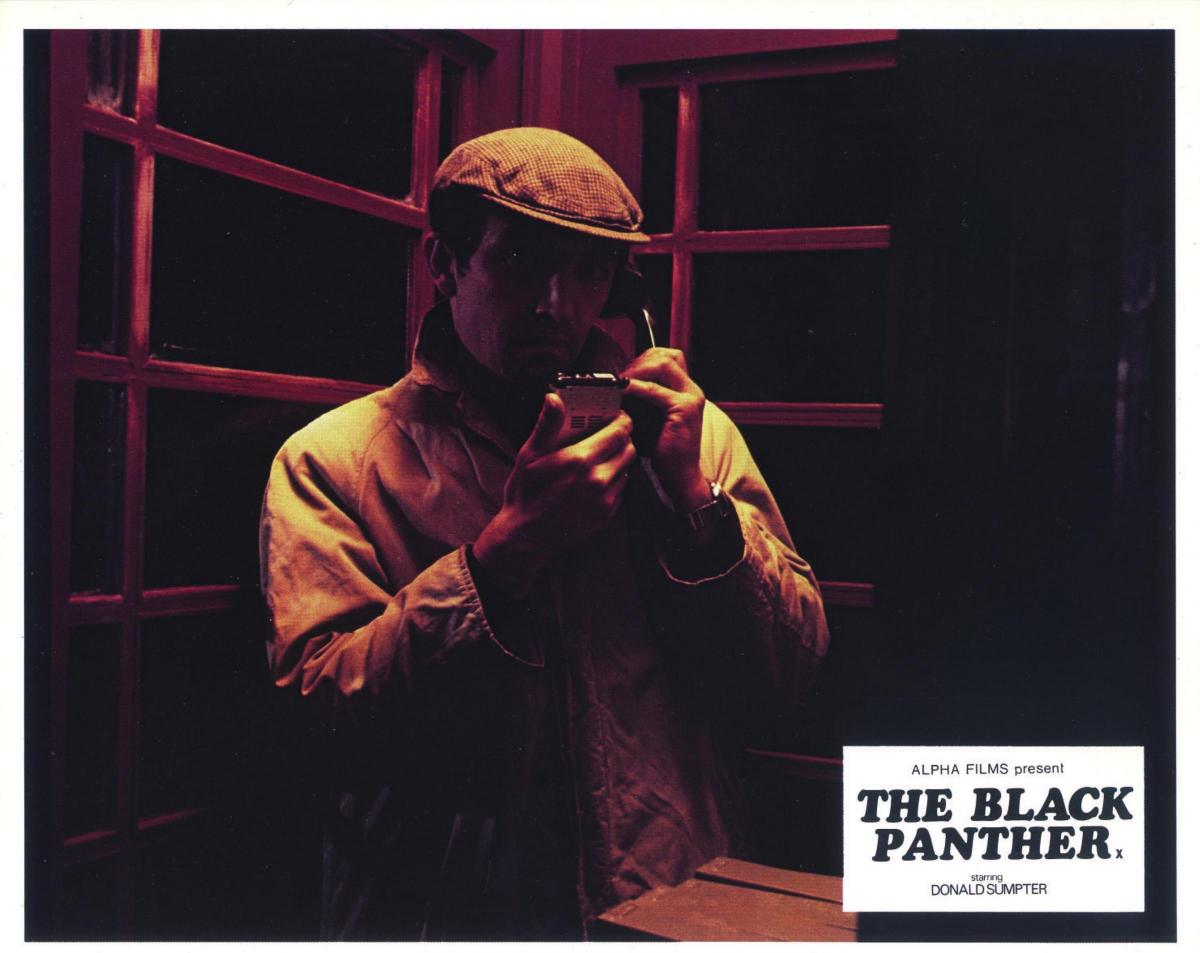

Ian Merrick certainly thinks so. Back in 1976 he was a young director with aspirations to make a thriller, in the style of John Fowles’ The Collector, about a deviant who kidnaps a young girl.

He was persuaded by producer Stanley Long, the producer of a string of sex comedies including Adventures of a Plumber’s Mate, to drop his project and to instead focus on something that was dominating the news: the case of the Black Panther.

Merrick never considered the movie to be exploitative, and points to the making of Ten Rillington Place, starring Richard Attenborough as John Christie, as an example of a film that focused heavily on a serial killer’s murders.

It was deemed acceptable because it carried a weighty message of anti capital punishment following the wrongful execution of innocent Timothy Evans, who was hanged before Christie was caught.

Thus Merrick opted to tell the truth about Neilson. It was an unvarnished approach but it went down like a lead balloon.

Having approached the Whittle family for their co-operation and been rebuffed - Lesley’s brother Ronald said, “I know you’ll go ahead and there’s nothing we can do to stop you, but please show my family respect” - Merrick resolved to make a spare, ascetic portrait of what he calls “a bitter man, pathetic and desperate”.

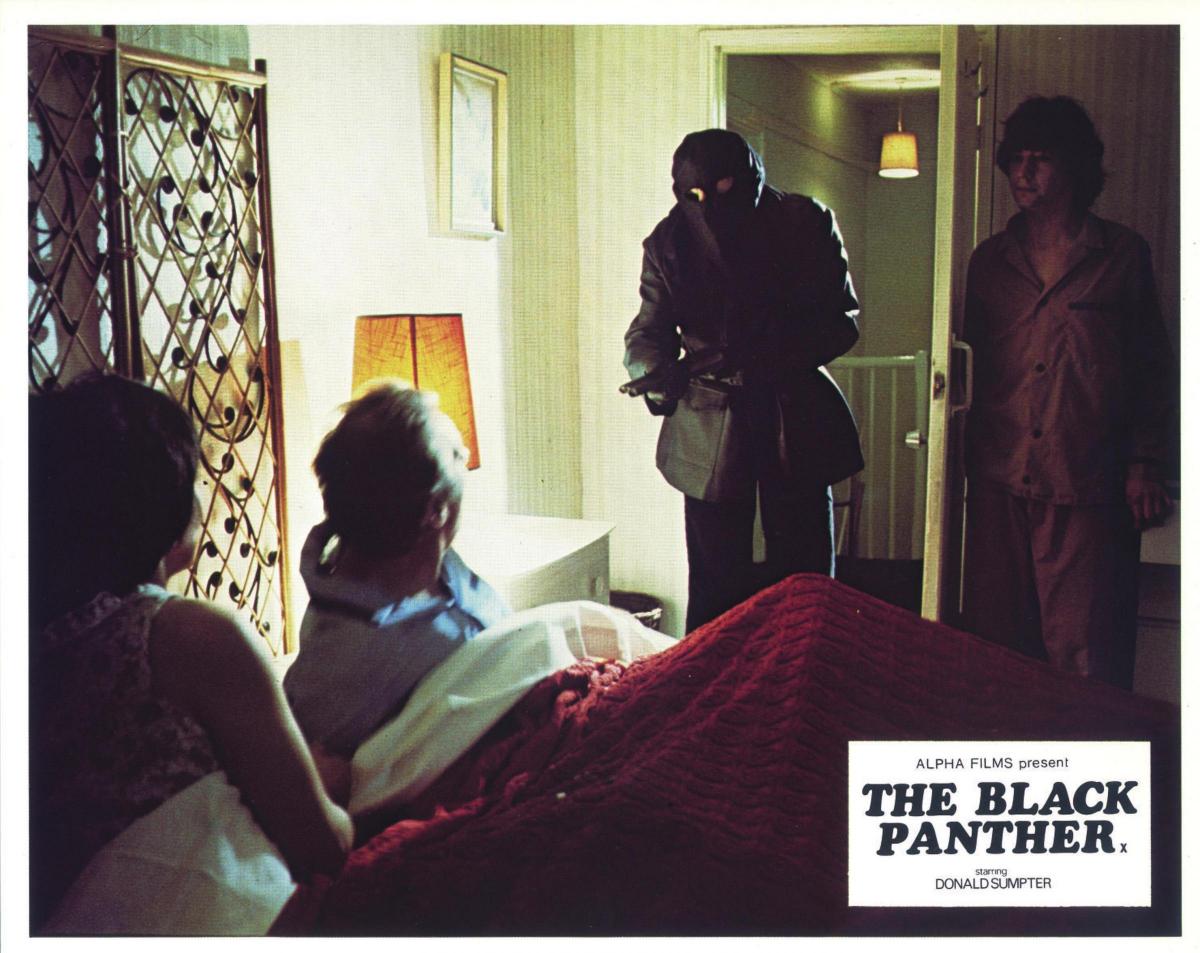

The film was shot in two weeks on a budget of £100,000. Theatre actor Donald Sumpter was cast as Neilson after the role had first been accepted by Ian Holm. He left the production after learning of the Whittles’ refusal to assist.

Scriptwriter Michael Armstrong told no one that he had accepted a commission to write the Neilson story. He based his original screenplay on court transcripts, ensuring that every word Sumpter uttered was based on recorded fact.

But there was one scene that made Merrick nervous: the kidnapping of Lesley Whittle. In his testimony Neilson revealed that the girl was naked when he woke her. Armstrong argued she should be naked in the film “otherwise it’s a lie or the suspicion of a lie to everything else in the film.”

Armstrong added: “Ian had a lot of pressure on him and he was worried that it would be viewed as something gratuitous: that a teenage girl was going to strip off. It was just a hard fact: she was naked.”

Armstrong was profoundly affected by adapting the story of the Black Panther for cinema. Consequently he later turned down an invitation to write a movie about the Moors Murderers.

“There wasn’t even a second’s worth of thought before I said no,” he recalls.

In the US there have been scores of movies about serial killers. In the UK the likes of Ian Brady and Myra Hindley, Peter Sutcliffe and John George Haigh have been largely left alone. Armstrong has his own thoughts on that.

“The Moors murders broke taboos because it was children. And the Yorkshire Ripper was believed to be killing prostitutes until he murdered a 16-year-old girl who wasn’t a prostitute," he said.

The difference with Neilson, says Armstrong, is the issue of class. Lesley Whittle was a nice, respectable girl. If Neilson had snatched a prostitute or a drug addict it would have been very different. By choosing a middle-class girl from a comfortable family Neilson broke all the taboos that were embedded in British society.

“The mistake would be to try to capitalise on that. The phone hacking scandal only really exploded when they hacked Milly Dowler’s phone. You break a taboo when you cause suffering to people that do not deserve it. That was never our intention," said Armstrong.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article