WORLD War 1 didn't only involve human beings. The part played by animals - until the popularity of Michael Morpurgo's book War Horse and the film and the play of the same - has been overlooked.

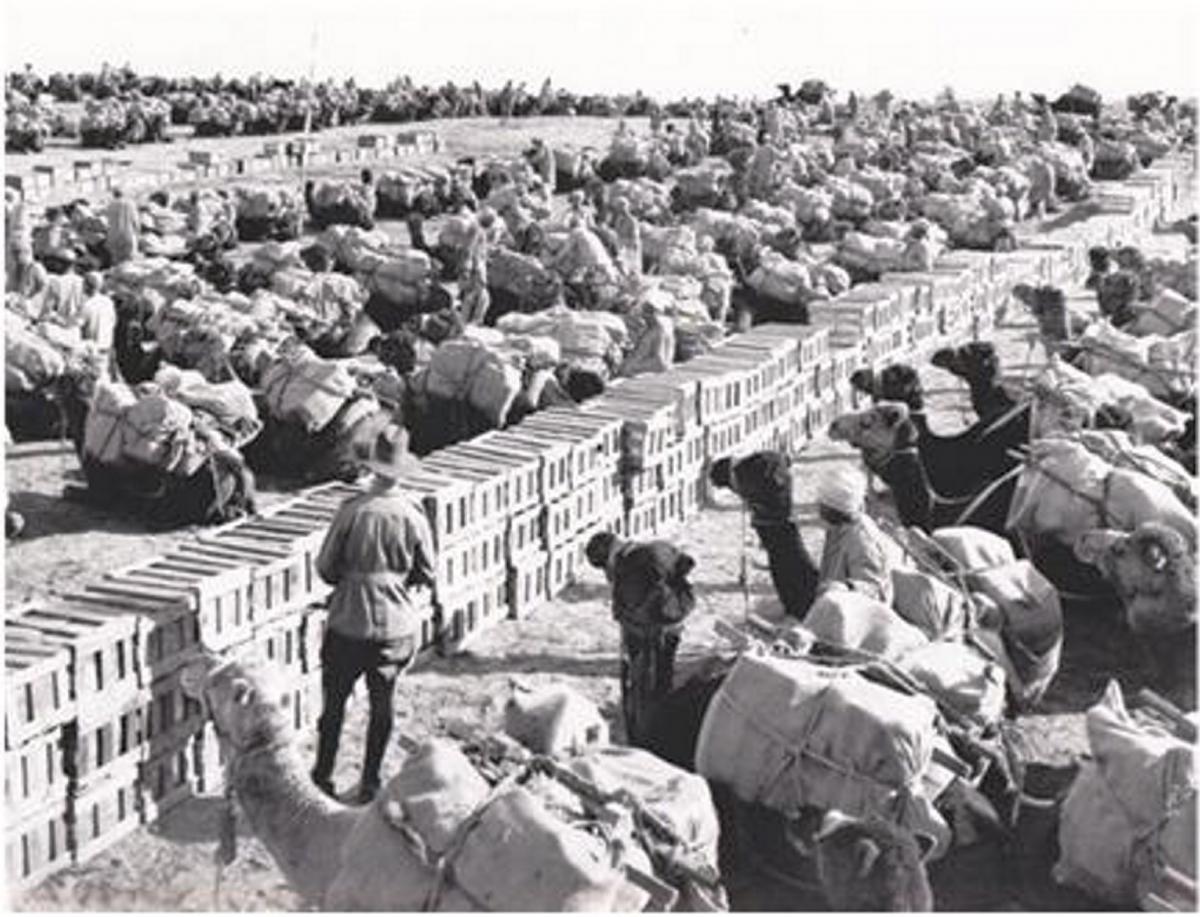

Historical documentaries described political tensions that led to war, the numbers of people that war consumed and the weapons they used to do it; but until recently they ignored the role played by horses, donkeys, camels, cattle, dogs and pigeons.

But looking at the back page photographs of the Yorkshire Observer in the early weeks of August 1914 the presence of horses gives the impression that the coming conflict was going to be fought by artillery and cavalry.

In his book War Horses, Simon Butler estimates that a million horses were drafted to the battlefields of the Western Front, of which only 62,000 came back to Britain after the war. The number of horses killed serving the various combatants during the four-and-a-half years of fighting ran into the millions.

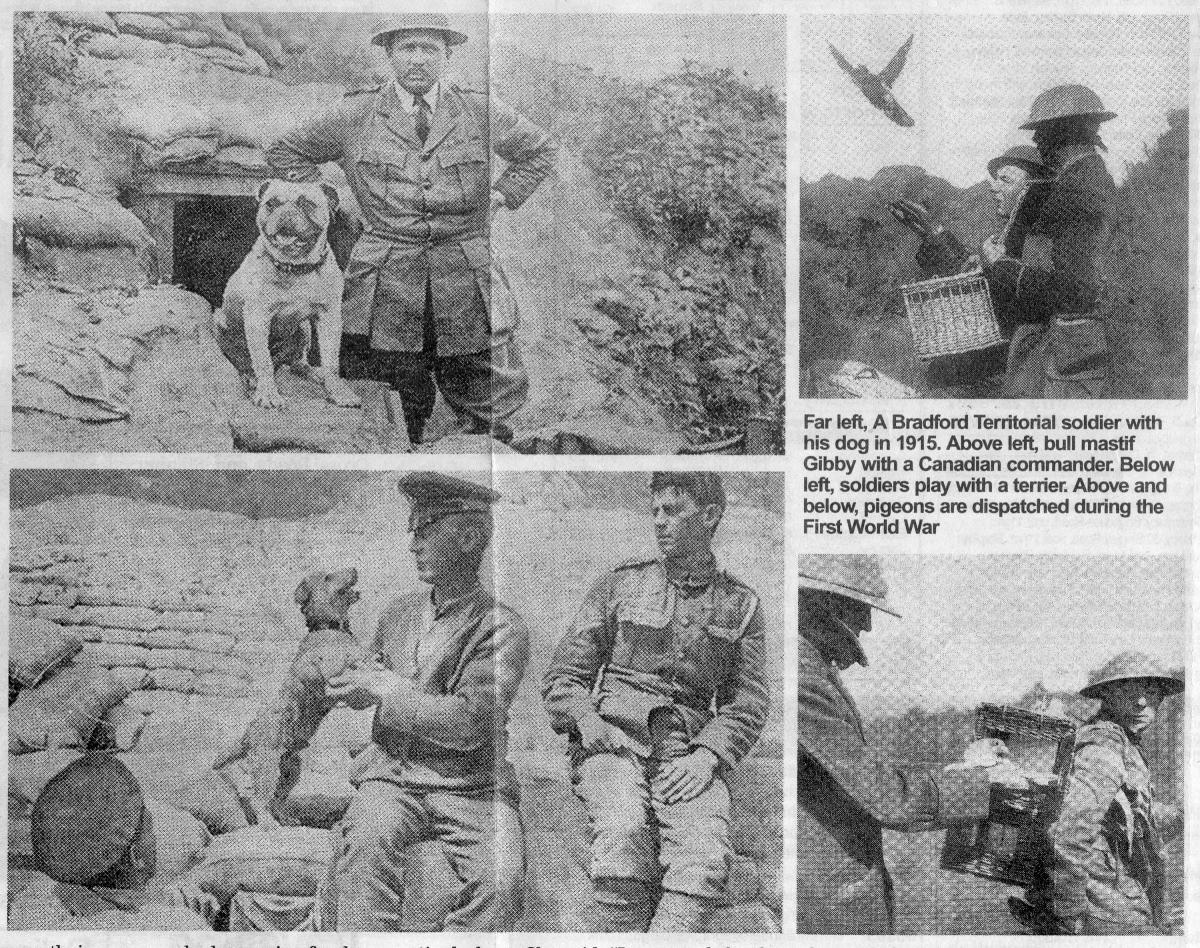

The armed forces of Austria and Germany, Britain, France, Belgium. Sweden, Russia and the United States, also made great use of dogs - more than 50,000 of them. Of these it's thought that 7,500 perished in active service. London's Hyde Park includes an impressive Animal in War memorial.

Among the most popular breeds used were Airedales, Doberman Pinschers, German Shepherd Dogs, and terriers. Terriers were trained to hunt and kill the other ubiquitous animals on the Western Front - rats, that proliferated among hundreds of miles of trenches and the water-logged, shell-holed waste-lands between them.

Military dogs, depending on their size, intelligence and training, were used as sentry dogs, scout dogs, casualty or mercy dogs, messenger dogs and mascots. They were also battlefield companions, lighter and nippier on their paws than either men loaded down with donkey-loads of kit or horses lugging field-guns and ambulance vehicles through rutted mud.

Dogs were faster and harder to shoot at. That's why they carried messages, usually in a tin cylinder, and carried medical aid to wounded and dying soldiers in cratered and barb-wired no-man's land.

Casualty dogs, originally trained by Germans in the 1800s, were equipped with medical supplies. Having made their delivery they would often stay with a fatally wounded soldier until he died.

Czar Nicholas II of Russia had 23 Airedales as well as Dobermans and German Shepherds attached to the Hussars of the Imperial Guard. The German military preferred English Airedales to their own specially-bred and trained war dogs. The British waited until 1917 to give Lieutenant-Colonel Edwin Richardson permission to set up a war dog school at Shoeburyness.

Dogs trained fior war duties wer usually taken from London's Battersea Dogs' Home. As demand grew, dogs' homes in Briistol, Liverpool, Birmingham and Manchester were drafted. Then UK police forces were asked to send stray dogs to the war dog school.

Other messenger carriers, of course, were pigeons. Motorcycle despatch riders were sometimes asked to carry pigeons in a wicker basket. The birds were used to deliver messages where no other means of communications existed.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here