EVERY man has his breaking point – that critical moment when the mark has been irreversibly overstepped and swift, incisive, perhaps even violent action is the only recourse.

Paul Weller’s comes about 30 or so minutes into a Jam gig at Swindon.

Understandably sickened by a barrage of saliva discharged from a rabble of pogoing oiks, Weller – whose barbs are usually confined to his songs – unstraps his shiny brown and white Rickenbacker and plunges head-first into the throng.

Within blinking space, bass player Bruce Foxton is in there with him; fists fly as two-thirds of one of the era’s sharpest bands clunk some Wiltshire heads and, one hopes, bloody a few well deserved noses.

Sorted, our nattily attired warriors swagger back on-stage, momentarily re-adjust their suits and resume an incendiary set, channelling whatever aggression is left – and there appears to be plenty – through the music.

The somewhat perverse, wholly unhygienic act of showing appreciation for your favourite bands by unleashing Agincourt-like volleys of spittle into their midst is a less than savoury aspect of the otherwise momentous punk era.

Such a scenario produces a similar response – this time, one of pure pantomime which still makes me chuckle – when The Stranglers come to town.

Let’s face it, they’re a grim looking bunch of rogues, The Stranglers: the sort of unshaven rascals you’d find in a press gang.

You wouldn’t mess with them – not unless you’re a naïve Swindon punk under the hopeless illusion that it is de rigueur to spit at your heroes.

Glaring down at the unfortunate offender with a mixture of contempt and relish, singer/guitarist Hugh Cornwell and bass player Jean-Jacques Burnel are not slow to react.

Man-handling the hapless fellow onto the stage, they promptly whip off his trousers – swiftly followed by his boxers – and administer a sound public spanking.

A pair of milky white cheeks turn a vivid shade of crimson – a mixture of pain and embarrassment, one assumes – as the rest of us roar our amused approval.

While The Stranglers gig is at the Oasis, The Jam’s is the Brunel Rooms, the imminent re-opening of which on August 1 brings to mind a spate of shows during a period that – for me, anyway – was the venue’s heyday.

The punk era – roughly 1976-78 – shone brightly before the inevitable burn-out, leaving a string of era-defining if often hazy memories; that, and a bunch of classic pieces of plastic.

The best thing about punk? That virtually all of the bands-of-the-moment wowing trendy Londoners soon head for the provinces – and that includes Swindon.

It sparks a fierce if undeclared war between Bill Reid and John Norman’s Brunel Rooms and Ian Reid’s (no relation) The Affair; rival town centre venues locked in combat over who can lure the most prestigious bands to Swindon.

And there is only one winner: us, of course, the fans.

Firing an initial salvo on a bone-chilling December night in 1976, The Affair hosts The Vibrators – Swindon’s first punk gig.

Hardly a safety pin is to be seen as a smattering of intrigued punters observe the group, fresh from supporting the Sex Pistols, perform their new single, Pogo Dancing along with similar fast, furious fare.

“Hey this is your chance/To do the pogo dance/So get both your feet up off the ground/What goes up – must come down.”

Johnny Rotten and Joe Strummer, presumably, are not losing any sleep. But who cares; Swindon is on the punk map.

A few years before their callous debagging of an irksome Swindon punk The Stranglers, too, play The Affair. It is March 1977 and The Stranglers are thrilling – but why aren’t there more people here.

To paraphrase one of their songs that night, something better change; at least, if Swindon is to become a magnet for this exciting crop of new bands.

A couple of weeks later, a strange one. Andy Warhol actress Cherry Vanilla has reinvented herself as a pouting punkette and plays The Affair. Myself and an Adver colleague are in the dressing room after the gig asking her about Andy.

Sitting nearby quietly drinking tea are her backing band including bass player Gordon Sumner and drummer Miles Copeland.

They are paid £15-a-gig on the condition that their new group The Police take the support slot. A year later they have bleached their hair and are stars.

Next, The Clash: an apocalyptic night at The Affair involving the fire brigade, the destruction of the band’s equipment and the re-writing of London’s Burning to Swindon’s Burning (remembered at length in the Adver, 1-5-13.) I still have my National Union of Journalists Card from that night, on which is scrawled: “double brandy and lemonade, double vodka and lime, double whisky, double vodka and orange.” And I’m pretty sure I never saw change from a fiver.

Time for the Brunel Rooms to enter the fray – and how! Can anyone today imagine The Ramones and The Talking Heads on the same bill in Swindon?

Our gritty Wiltshire town, for a few hours at least, is deposited onto the garbage infested streets of downtown Manhattan, somewhere between legendary rock’n’roll dives CBGB’s and Max’s Kansas City.

The Adver’s review bellows: “Ramones Smash Sound Barrier.”

At this point the feeling at both venues goes something like: “If you get The Clash, we’ll get The Ramones.”

The Buzzcocks play The Affair, generating long queues outside. My colleague Steve Kelly and his mates are locked out.

They climb onto the roof and pile in through a sky-light, crashing onto the desk of assistant manager, amiable Brummie Dennis Detheridge (who luckily, isn’t at home at the time).

Their drinks are waiting – courtesy of me – lined up at the bar.

Eschewing the usual pre-gig drink at The Belle Vue in Old Town (now Longs) a bunch of us from the Adver get to The Affair early for Elvis Costello and The Attractions. It is August ’77.

Surprisingly Elvis – new hero of the music press – is on his own, perched on a stool at the end of the bar having a beer.

We respect his privacy to enjoy a quiet snifter before going to work. Well, most of us.

A friend, Pat ‘Harold’ Harrison shows no such restraint. He feels impelled to accost the bespectacled star, greeting him like a long lost brother with a hefty thump on the back and a bear hug. “It’s Elvis isn’t it – Elvis.”

Elvis is appalled. I can still recall his expression; indignation, horror, outrage… maybe that’s why he performs such a spiky set.

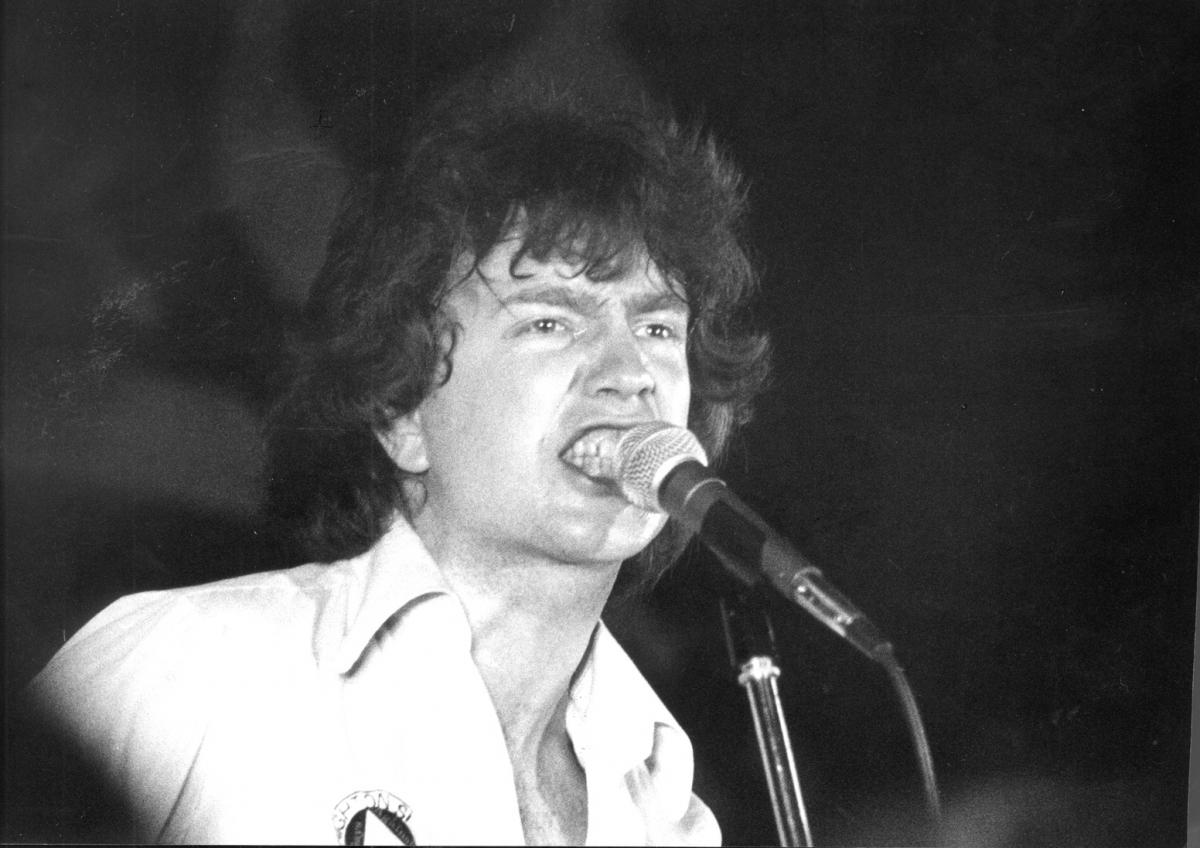

At the Brunel, Bob Geldof is angry, too. He wants to hit someone. But unlike Paul Weller he doesn’t; instead, he storms off-stage and refuses to come back.

His problem? The old one. “Why do they do this,” he remonstrates with the management.

An announcement is made. If the spitting doesn’t stop, the Boomtown Rats will. Jeers, cat-calls, but the future Sir Bob returns and mouth-to-Bob missiles cease.

There are moments of fleeting glory: At the Brunel, Ulster’s Stiff Little Fingers brilliantly, brutally overhaul Bob Marley’s Johnny Was with a furious military beat (“A single shot rings out in a Belfast town”); The Saints barnstorm through I’m Stranded at The Affair – yes, Aussies can do it too.

The finale of a joyous Tom Robinson Band gig at The Brunel is an absolute peach.

After Power in The Darkness and 2-4-6-8 Motorway we are in the mood for a sing-song.

Such fun to be among several hundred beery Swindonians as we bawl in unison: “Sing if you’re glad to be gay/sing if you’re happy that way.”

It’s only a guess, but I reckon most of us here are straight: then again, so – apparently – is Tom.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel