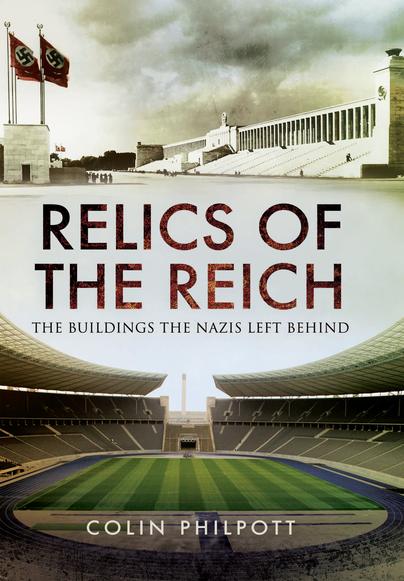

Relics of the Reich by Colin Philpott, published by Pen and Sword, priced £19.99

Colin Philpott, former chief executive of Bradford Breakthrough, on his book telling the story of the Nazi architectural legacy:

"Consider these news headlines from Germany: ‘A Nazi holiday camp on the Baltic Coast of Germany is opening as luxury seaside apartments’, ‘The City of Nuremberg is debating spending £60m on stopping the Nazi Party Rally Grounds crumbling’, and ‘Buildings at the Dachau Concentration Camp site near Munich are being used to house refugees’.

These are headlines not from 1930s Nazi Germany but from Germany in 2016.

A great deal has been written about how it was that Germany fell under the spell of the Nazis but rather less about how the country has dealt with the Nazi legacy post-1945. The headlines mentioned above illustrate perhaps the most surprising point about the Nazi architectural legacy – that much of it still exists and that much has been put to new uses - often controversially.

For example, the vast Prora-Rugen Nazi ‘Strength through Joy’ holiday camp built as a sort of Nazi-Butlin’s on the north German coast is still there. It remained unfinished in 1939 when war broke out and no one ever had a holiday there under the Nazis. For many years after the war, it was used as a military facility but now developers have acquired many of the blocks and are turning them into luxury holiday apartments.

More controversial is the debate currently underway in Nuremberg – home of the Nazi Party Rally Grounds built by Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, to stage the giant propaganda fests held annually during the Nazi era. There is a museum on the site and much of the grounds have been repurposed for housing, sports facilities, an indoor arena and parkland. However, the iconic grandstand building, including Hitler’s podium, remains but is slowly crumbling. Nuremberg has decided in principle to spend £60m to stop it falling down on the grounds that it is an important historical building with a powerful story to tell to modern generations about the horrors of the Nazi period.

And, remarkable as it may sound, Syrian refugees are currently being housed in buildings that once formed part of the Dachau Concentration Camp – most of which is preserved as a memorial.

Whether or not it is right to use former Nazi buildings in these ways is an interesting debate and the answer depends, in my view, on how closely the buildings were associated with the terror machine of the Third Reich.

The sites most associated with the genocide and the terror of the Nazis are, of course, the concentration camps but also places like the Gestapo Headquarters in Berlin and the Wannsee House where senior Nazis met to decide on the ‘Final Solution’. Of the estimated 15,000 camps established in all countries by the Nazis, many were destroyed either by the Nazis themselves or by the Allies soon after the war. Seventy years on, though, a significant number remain as memorials and museums. The original impetus to preserve them as memorials was, in most cases, as a result of ‘victim pressure’. More recently, however, that has changed and now most concentration camp memorials in Germany are supported financially by the Federal Government.

The second category is those sites associated with the German war machine – the factories, the U-boat pens, the rocket launch sites and the command bunkers. Some remain in military use and some factories utilised for the war effort, such as the VW factory in Wolfsburg, remain but have been converted to peaceful ends. Both at Valentin and Wolfsburg there is now acknowledgement of the suffering that occurred there principally through the use of forced labour.

The third main category covers those places specifically built by the Nazis as statements of their power, values and view of the world. These include the Nuremberg Rally Grounds, the sites built for the 1936 Olympics, new airports in Berlin and Munich, the party headquarters in various cities and the private homes and grounds acquired or built for the Nazi High Command. Most of the Olympic sites are still in use. Many Nazi administration buildings have been put to new uses. Although most homes of senior Nazis were deliberately demolished by the Allies, or later by the post-war German authorities, some do remain as private residences - including Albert Speer’s architectural studio near Berchtesgaden.

My own experience of visiting many Nazi sites in Germany leaves me in no doubt that, overall, Germany is a country handling its difficult past seriously and with a degree of critical reflection. The memorial sites are solemn and chilling and no-one who visits Dachau or Auschwitz can fail to be impressed by the simple commemoration of multiple victims that these places now offer. Visiting the documentation centres in Nuremberg, Berchtesgaden, Berlin and elsewhere, did not leave me feeling that there was an attempt to explain away and exculpate.

The Nazis did not have a monopoly of terror and human history is sadly littered with repugnant regimes. It will remain vital, however, that the story of how Germany became the Third Reich, and the ensuing catastrophe, is told for future generations. The history of the buildings and spaces where that story unfolded is a crucial element in ensuring that this happens."

* Relics of the Reich is available at pen-and-sword.co.uk/Relics-of-the-Reich-Hardback/p/11862

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here