September 8th: ‘Return to Hell.’

Heading inland from the coast, Fred Harrison’s regiment marched for three days before arriving back on the Western Front. It was 1917.

Just before, they had found an unoccupied house whose occupants had fled. Here, Fred had ‘a real bed to sleep in for a few nights.’

Now he was marching along a route past scenes of sheer horror. ‘Bodies of men and decomposing horses and mules everywhere.’

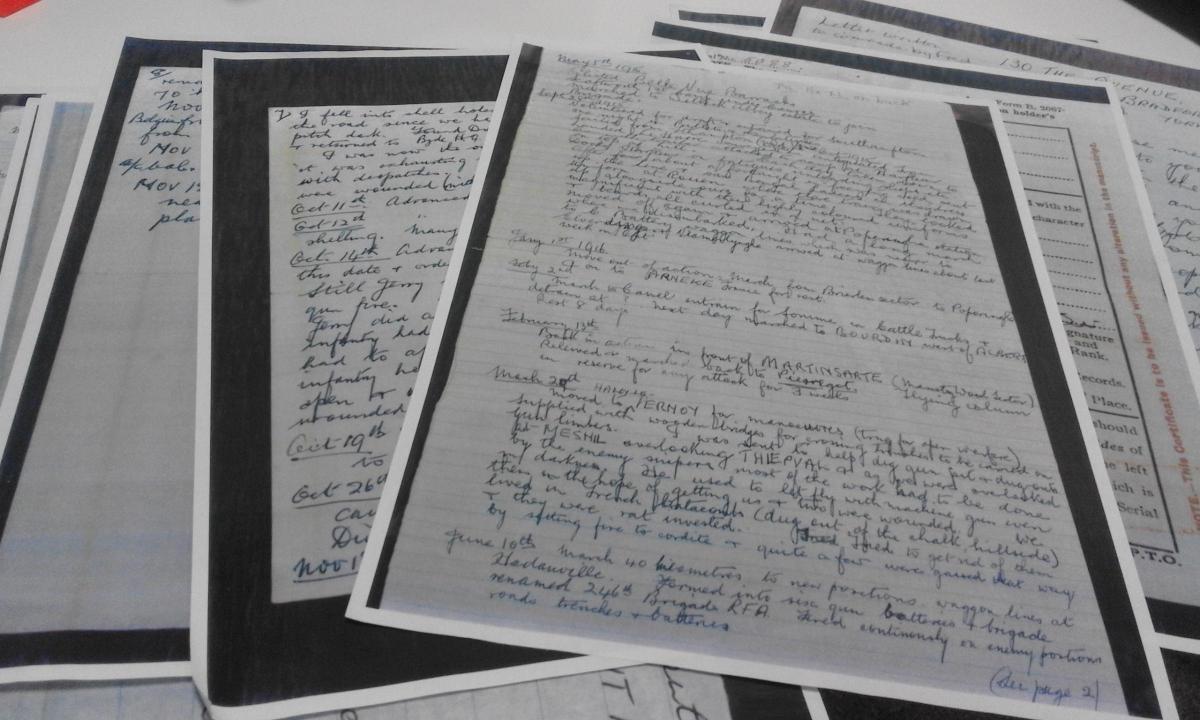

Fred, a police sergeant who served in Bradford from 1919 to 1947, recorded in a diary his experiences of the First World War, laying down in neat handwriting the sights, sounds and horrific conditions in which he and the other men fought for their lives.

September 9th sees him write: ‘This ground had been captured from Jerry during previous attacks on the Passchendaele Sector,’ he writes. ‘We were lucky to find wonderful German dugouts 20 feet dee and shell-proof, perhaps covering an acre, and a dozen entrances.’

Fred’s observations paint a vivid picture of the carnage left behind. ‘Batteries march through Ypres, past ruined cathedral, Cloth Hall and up Menin Road. Passed ruined villages. The approach road consisted of planks, ground full of shell holes full of water, could hardly find place for guns.’

The push forward was relentless, to advance just a short distance.

October 6th: Attack 5.35am infantry advances a few hundred feet.

October 9th: ‘Attack again capture a ridge 1000 yards distant. Troops suffer heavy loss from well-constructed pillboxes. Shocking weather, excessive rainfall and gales.’

October 12th: ‘3rd attack. Capture a few hundred yards of useless ground. Suffer heavy casualties and infantry return to own trenches.

October 13th: thunder and hailstones all day. Heavy Jerry shelling all day.

Another piece of ‘useless ground’ was captured on October 26, in ‘terrible’ weather conditions…’suffer terrible casualties. British and German dead are everywhere and no attempt can be made to collect and bury dead. Those who died on the approaches to positions on plank and duckboard tracks sank into three feet of mud and the tracks were surrounded by buried horses and men. An attempt by one hundred troops with drag ropes failed to pull one gun out of the morass.’

He summaries the advance: ‘Over a period of six weeks we attacked seven times and captured five miles of flooded, uninhabitable ground.’

More than 240,000 British soldiers died in the Passchendaele offensive, of which 9,000 were recorded missing.

‘If we had attacked many more times our army would have been almost decimated,’ writes Fred.

Fred died in 1989 aged 94. His daughter Audrey Harrison, of Woodside, now aged 88, recalls how, many years after the war ended, her dad copied out the entries from his old battered diary which was falling apart, on to clean sheets of foolscap. But he never talked about his experiences.

“He would never talk about it, or tell us anything about the war” she says.

A member of the Royal Field Artillery, Fred looked after the horses that pulled the guns. One entry, is dated October 9th, 1918, when the men had reached the French town of Neuville-St-Remy, a suburb of Cambrai which the Germans had recently vacated. It reads:

‘So I leave Brownie, with whom I had been talking, to fetch our horses from the shed about 20 yards away. As I was entering the shed there was a terrific explosion followed by screaming, one of the heavy shells had dropped short, amongst us.

‘I ran back into the field and pick Brownie up, most of his clothing had been blown off, he was dead, but did not show any sign of blood.’

Later, Fred’s horse, Rene, receives a bad cut on her hind leg as many of the animals become tangled in broken telegraph wires. ‘I struggle for nearly half an hour to extricate them,’ says Fred. Many men and horses died that day, and Fred lists the casualties in his regiment: ‘Brown, Mackenzie, Lilley, Day and Hillier…Swift and Kelly,’ and the many wounded.

As the war ended, Fred was the last surviving member of the original group of 1915 signallers that left for France.

During his time overseas, Fred received the Military Medal for bravery, but did not tell Audrey or his wife Annie why.

Audrey is very proud of her dad. “Yes, I am so proud of him, and so was my mum.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here