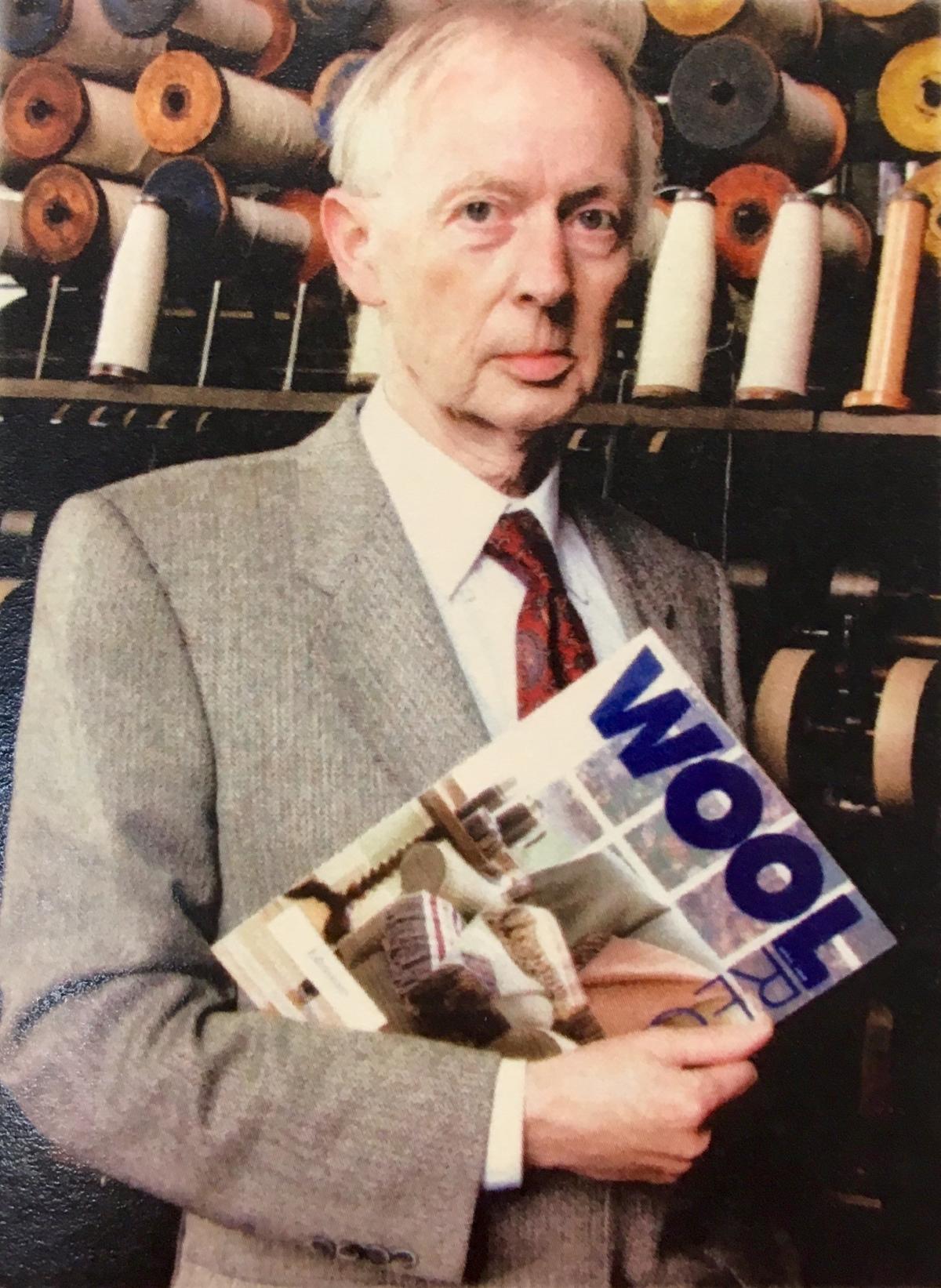

THE late Mark Keighley spent his working life steeped in Bradford’s two major industries - wool textiles and engineering. After several years editing the company newspaper of Hepworth & Grandage, one of the city’s “Big Three” engineering firms, he joined the Bradford-based Wool Record in 1962. The wool-textile magazine had a global circulation, and during the many years Mr Keighley wrote for and later edited the publication, he became an authority on all aspects of the industry.

Here we publish the latest extract from Mark Keighley’s memoirs, The Golden Afternoon Fading, looking back at Bradford’s industrial, business and social life as its industrial golden days began to pass into history.

“From time to time, Labour councillors would grumble that Bradford was overrun with woolmen. Deliberately, perhaps, they failed to point out that the city had never been wholly dependent on one industry, or that in the late 1950s Bradford had more men (14,200) in the engineering and metal-manufacturing sector than in textiles (14,100). Statistics show that wool mills provided work for more than 21,000 women in the Bradford area in the period under review. A staggering figure. The next highest total was 10,000 women employed in “personal service”, of whom 3,700 worked as domestic servants and 2,300 as charwomen.

But statistics were the last thing on my mind as I walked up the stairs at 91 Kirkgate that December morning in 1962, in what seemed to be a silent and deserted building. I was entering a different branch of British industry and a vastly different world. In his autobiography Margin Released, the Bradford novelist and playwright JB Priestley recounts how he felt on his first day as a junior clerk at a wool importer’s office in the city’s Swan Arcade. “As soon as you were carried up in the lift you were walled in by the Bradford trade and the price of crossbreds,” he remarked. He might well have added that in the Bradford wool trade everyone seemed to be related to everyone else, as I was to discover in the course of time.

Mike Priestley and I were each allocated a desk in the main editorial room. From the windows we had a bird’s-eye view of Kirkgate and Novello’s white-fronted fashion shop at the foot of Westgate, and Kirkgate Market beyond. The room was furnished with bookcases containing bound volumes of the Wool Record and other learned publications; was fitted with a faded Turkey Red design carpet; and equipped with ancient Underwood typewriters weighing a ton. When Jack Wilks (the deputy editor), Randal Coe (senior reporter) and Alan Murray, Mike Priestley and I were busily hammering out stories and statistics for the next edition, the room was as noisy as a shipyard on the River Clyde. I spent the first few days listening and watching. The senior members of staff were preparing the stories for that week’s issue. One was about Alan Smith, a director of Joseph Dawson’s, who’d returned from a two months’ visit to Russia and China, the principal sources of best white cashmere used in the Huddersfield and Hawick textile trades. Dawson’s also bought cashmere from merchants in Afghanistan and Iran.

He was a dashing figure and in the Second World War had acted as Douglas Bader’s wing-man during the Battle of Britain and been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. By the 1960s he and his co-directors in Bradford and Kinross in Scotland had turned Dawson’s into one of Britain’s most admired and profitable groups. One of his remaining ambitions was to ensure that wild fluctuations in the price of cashmere became a thing of the past. In the Wool Record’s opinion, he was a man to watch. He was knighted by the Queen.

In 1961 I’d attended a course in industrial journalism at the London Polytechnic and had been advised by brilliant Fleet Street tutors from the Daily Mirror and Daily Telegraph to steer clear of the “three R’s” (race, rumour and religion). Consequently, I was intrigued by a report that the Wool Record was preparing to publish. It emanated from Huddersfield auctioneers Eddison, Taylor & Booth, who were anxious to refute widespread rumours circulating in the Yorkshire textile trade that they (Eddison’s) planned to hold more than 40 sales of textile mills and machinery “in the near future”. That was a nervous reaction to the news in textile towns, but Eddison’s made it clear that the rumours were completely without foundation. Several years later, when mills were going out of business or being placed in administration almost weekly, my mind would go back to the Eddison report.

One of the pictures selected for reproduction in that issue served as a reminder that Christmas was approaching. It showed guests on the top table at a buffet dance at the Craiglands Hotel in Ilkley. The festivities were organised by Joseph Brennan & Sons, one of the most successful firms of wool merchants and topmakers in the Bradford trade. The men wore bow ties and dinner suits and the ladies wore stylish gowns and contented expressions, sipping champagne. Another year was closing in a mood of celebration. It seemed as if the good times would never end.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here