IT remains an unfamiliar condition to many.

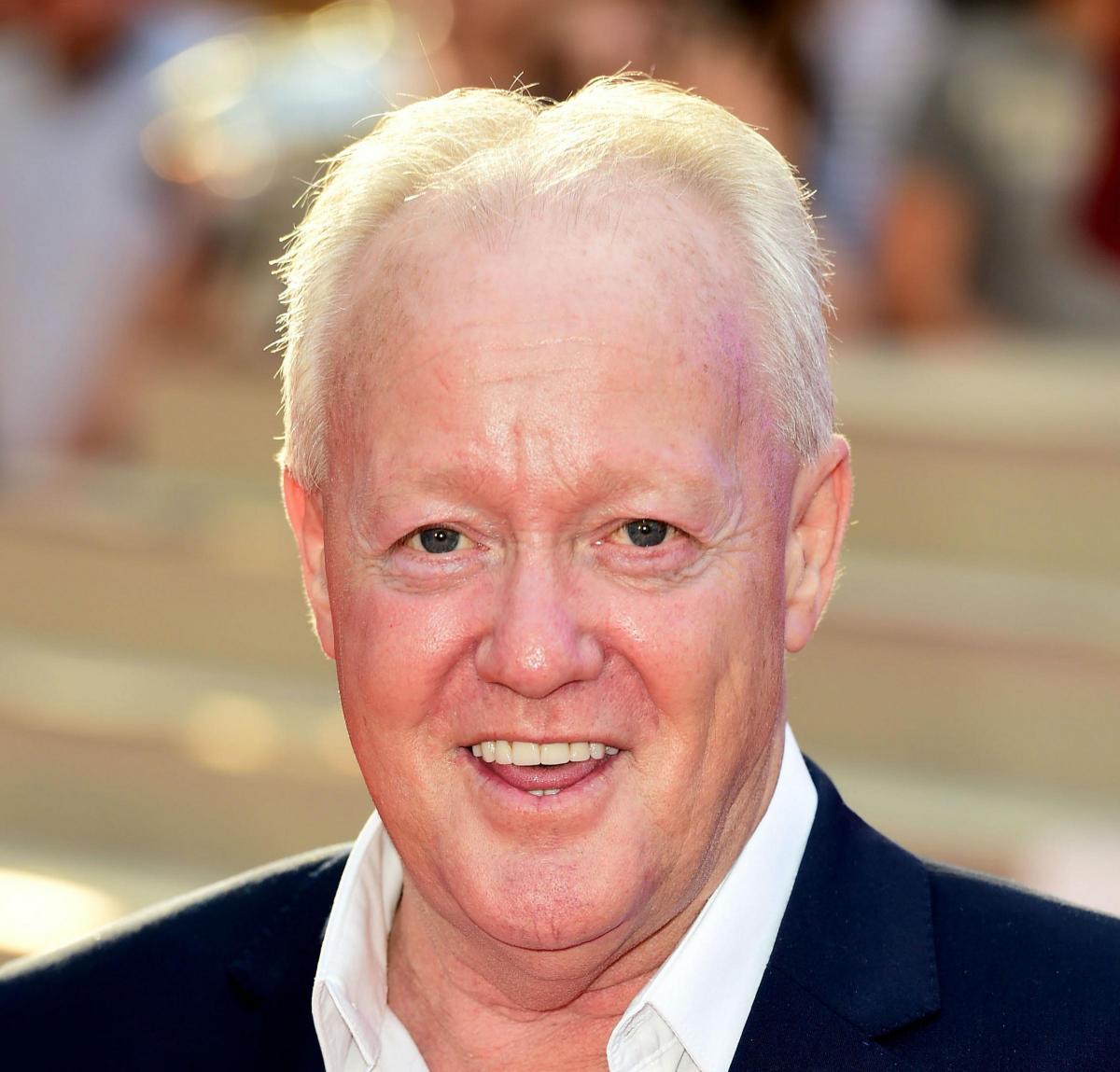

The death of TV legend, Keith Chegwin, the personality many of us grew up with in our youth watching hit shows such as Multi-coloured Swap Shop, Saturday Superstore and Cheggers Plays Pop brings home the reality of its existence.

Another high profile sufferer of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis is the mum of TV presenter, author and model, Katie Price.

For those with first-hand experience of IPF - one of many types of interstitial lung disease - nobody can begin to explain how totally and utterly devastating and depressing it is to see the person that you love struggling for every breath they take as the disease tightens its grip.

The restrictions and limitations; the amount of energy they don’t have but are determined to try and muster for those basic daily tasks we all take for granted such as washing and dressing is beyond belief unless you have lived with it or through it caring for a loved one.

Conversation - something always enjoyed - becomes a chore because there just isn’t enough energy to speak the words you want to say any more. This is the reality and, believe me, it is heartbreaking.

I long for the day when IPF garners more attention and I suspect one of the reasons why it probably doesn’t is many lung conditions are often perceived to be due to smoking.

Yet I am aware of sufferers of IPF who haven’t smoked. Nobody can understand why they have been burdened with such a cruel and devastating disease but that could be said about many other conditions and diseases which is why research is all the more imperative to improve treatments and, hopefully, one day find a cure.

So what is Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis? IPF is one of the many types of interstitial lung disease (ILD). Interstitial means that the disease affects the interstitium, a lace-like network of tissue that supports the air sacs (alveoli) in the lungs. Idiopathic means the cause of the condition is not known. IPF is the most common type of ILD.

IPF is a build up of scar tissue in the lungs making them thick and hard. This fibrosis makes it harder for lungs to take oxygen from the air we breathe. It is characterised by worsening breathlessness and cough.

IPF is understood to be more common in those that have been exposed to dust from wood, metal, textile or stone or from cattle or farming. Infection with particular viruses could be another cause.

Currently there is no cure, although new drug treatments have recently become available bringing hope to those living with IPF, of which there are around 32,000 in the UK.

It has already been identified that IPF, bronchiectasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have a lack of effective treatments to halt disease progression despite their heavy burden on patients.

The British Lung Foundation (BLF) has appointed three highly distinguished Research chairs, Professor Toby Maher, Imperial College London; Professor James Chalmers, University of Dundee and Professor Louise Wain, University of Leicester to bring pioneering research and international leadership to these three disease areas.

Ian Jarrold, Head of Research at the British Lung Foundation, says: “We witness first-hand the devastating consequences that the long-term neglect of lung disease can have on patients and their families. Considering the impact diseases like bronchiectasis, COPD and IPF have on a patient’s quality of life, the lack of support and treatment options available is wholly unacceptable.

“Professors Chalmers, Maher and Wain’s forthcoming work has the potential to improve our understanding of these diseases, and provide personalised medicine - something which has already led to huge improvements in the treatment of many cancers. Their work will provide families dealing with a lung disease diagnosis more hope for the future.”

Dr Leanne Cheyne, Consultant Respiratory Physician at Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust says it is estimated in Bradford there are at least 350 people living with the condition. Yorkshire and the Humber has one of the highest prevalence’s of IPF in England and the number of cases are continually increasing.

But there is hope: Dr Cheyne explains through specialist centres like Leeds there is life-sustaining medication that is likely to increase life expectancy by a further two to three years.

For more information visit blf.org.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here